IST,

IST,

Financial Inclusion through Microfinance - An Assessment of the North-eastern Region of India

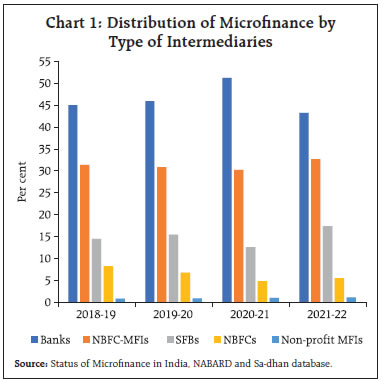

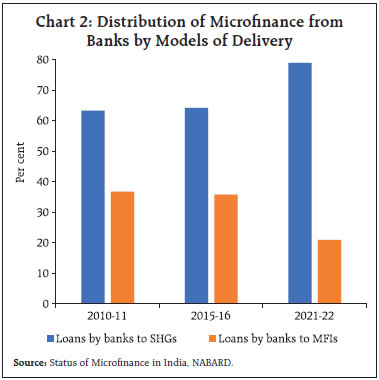

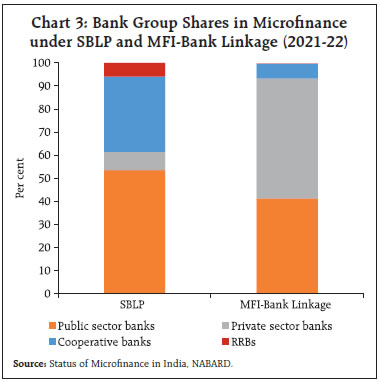

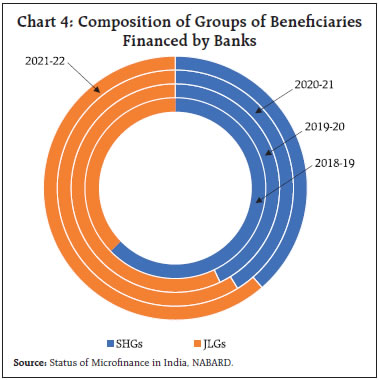

by S. Chinngaihlian^ and Pallavi Chavan^ Microfinance has been a facilitator in India’s endeavour towards financial inclusion. It took roots in the southern region, but has over time spread to the historically under-banked eastern and north-eastern regions. This article documents the spread of microfinance in the north-east. Despite a smaller share in the total microfinance portfolio, the north-east scores reasonably well on most indicators of access and usage of microfinance. However, there are state-level differences, underscoring the need for sustained focus on the region through policies, such as the financial inclusion plans and Self-Help Group-Bank Linkage Programme. Introduction Financial inclusion has been a key priority for India. Since finance serves as a catalyst for economic development, the relevance of financial inclusion stretches beyond the realm of finance to socio-economic development. Its benefits, thus, do not remain limited to the beneficiaries alone but are economy wide. Since its inclusion as a policy objective by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in 2005, numerous policy initiatives have been taken both by the RBI, and the Central and State Governments for financial inclusion. Certain initiatives taken before 2005 have also majorly contributed to financial inclusion. Microfinance is one such innovative initiative. It originated in Bangladesh following the establishment of the Grameen Bank, and came to India in 1992 as a pilot programme, which was later developed into the large-scale self-help group (SHG)-bank linkage programme (SBLP) by the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD). In the 2000s, the SBLP was complemented by the microfinance institutions (MFI)-bank linkage model (RBI, 2008). As the programmes/models evolved, so did the policy approach towards microfinance. From being largely self-regulated during the 1990s and 2000s, it became more robust entity-specific regulation based, involving Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs)-MFIs in the 2010s, which finally paved the way to a harmonised approach involving all regulated entities in the microfinance sector in the 2020s (Rao, 2021). Over these decades, the microfinance sector has shown a rapid growth in terms of (a) its intermediating institutions starting with banks [commercial and cooperative, and regional rural banks (RRBs)], extending later to NBFC-MFIs, and more recently to small finance banks (SFBs), and (b) its clientele. Given its fairly long stint, it may be useful to analyse the regional distribution of microfinance in India, and its contribution to financial inclusion at the regional level, as attempted in this article. The article takes a closer look at the north-eastern region of India. The region is characterised by distinct geographical, topographical, geo-political and cultural features. It has been historically marked by limited physical connectivity and has also had a relatively under-developed banking infrastructure (Chavan, 2017). The region (comprising eight states) is often considered as a single entity, but every state is marked by a distinct demography, topography, culture/ethnicity, and economic and banking development. Although studies on banking development, particularly those analysing regional aspects, cover the north-east along with other regions (Shetty, 2005), studies with an exclusive focus on the north-east and its individual states have been few (Chavan, 2020). While there have been some studies on microfinance in the north-east recently (Roy, 2011; Sharma, 2017; Nath and Nochi, 2014), there is no study in our knowledge looking at financial inclusion in the north-east through the lense of microfinance, as attempted in this article. The existing studies on microfinance in north-east focus on SBLP, while this article analyses the entire ambit of microfinance intermediated through banks and other intermediaries. The article addresses the following questions: a. How is the regional spread of microfinance, particularly in the north-east compared with the other regions? b. Juxtaposing regional development of microfinance with banking development, whether and how far has microfinance helped in bridging the gap in banking development and served as a tool for financial inclusion? c. What are the intra-regional trends in microfinance in the north-east? Although microfinance has been in India since the early-1990s, the article focuses on the recent period to capture the period of financial inclusion; as noted earlier, the RBI formally adopted financial inclusion as a policy objective in 2005. The pandemic has affected every sector with implications for the microfinance sector as well (Sriram, 2021). Given the limited regional data for the recent years, the article discusses certain preliminary trends in microfinance during the pandemic period. The article is divided into six sections. Section II discusses how microfinance fits into India’s broader policy on financial inclusion. Section III provides select features of the microfinance sector. Section IV places north-east in a comparative context with other regions in banking and microfinance development. Section V discusses the state-level trends in microfinance within the north-east. Section VI provides the concluding observations. II. Microfinance: A Part of the Financial Inclusion Policy The financial inclusion policy, as espoused by the RBI and the Government of India as part of the financial inclusion plans (FIPs) and Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) is associated with meeting bank-specific targets of (a) opening bank branches/outlets; (b) opening basic savings bank deposit accounts (BSBDAs) for savings, payments and credit (overdraft); and (c) Kisan Credit Cards (KCCs) and General CreditCards (GCCs).1 Even though the introduction of microfinance in India predates the formal adoption of financial inclusion as a policy objective, it fits into the policy on financial inclusion in many ways. First, financial inclusion is defined as “the process of ensuring access to appropriate financial products and services needed by vulnerable groups such as weaker sections and low-income groups at an affordable cost in a fair and transparent manner by mainstream institutional players” (Chakrabarty, 2011). Financial inclusion is for the socio-economically vulnerable sections that are prone to be financially excluded. Microfinance too has a distinct focus on women from the economically weaker sections. The group-based lending under microfinance, which relies on social collateral also underscores the focus of microfinance on the asset-poor sections. Second, financial inclusion involves not just credit but also a bouquet of financial services, including deposits and payments. Microfinance under the SBLP involves the provision of savings and credit facilities for its beneficiaries; they are saving-linked before getting credit-linked. Third, the policy on financial inclusion, as evident from the definition, relies on regulated entities as intermediaries. The Indian concept of microfinance too relies on regulated entities, including banks, NBFC-MFIs and SFBs. The extensive involvement of regulated entities, in fact, has distinguished the Indian microfinance sector from those in other countries, relying on semi-regulated or self-regulated MFIs. III. Select Features of India’s Microfinance Sector Institutions Delivering Microfinance On account of SBLP, banks have been the first and foremost intermediary of microfinance lending directly to SHGs. With the growing popularity of MFI-bank linkage model since the 2000s, banks’ financing to MFIs has also picked up. While the size and operations of MFIs expanded, concerns emerged about the lending and recovery practices of these institutions (RBI, 2011). These concerns prompted the RBI to carve out a newer category of NBFC-MFIs in 2011, and institute a tighter regulatory oversight over these entities to be eligible for priority sector creditfrom banks.2 The regulatory oversight has facilitated a fairly disciplined growth of NBFC-MFIs, as they have emerged as the second-most important microfinance intermediary in recent years. SFBs were introduced in 2015 as a differentiated banking institution for financial inclusion. They have emerged as the third-most important intermediary in recent years, displacing the smaller players, such as other NBFCs and non-profit MFIs (Chart 1). Models of Microfinance Delivery for Banks Microfinance is delivered by banks to their ultimate beneficiaries, namely SHGs and Joint Liability Groups (JLGs), through two broad models/programmes. Under SBLP, it is rendered directly.3 It is intermediated through MFIs under the MFI-bank linkage model. SBLP has been the predominant model of microfinance delivery for banks (Chart 2).   Among banks, public sector and cooperative banks have been the key drivers behind SBLP. By contrast, private sector banks have preferred the MFI-bank linkage model (Chart 3).  Microfinance Beneficiaries The original idea of microfinance related to beneficiaries organised into SHGs under SBLP. JLGs were introduced in 2004-05 by NABARD for the mid-segmentclients under microfinance.4 In recent years, JLGs have emerged as a more important grouping of beneficiaries being financed by banks (Chart 4). Among SHGs, women’s groups have been the most dominant (Table 1). Moreover, the penetration of microfinance has been more in rural than in urban areas. About 67 per cent of the total SHGs were financed under the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) as compared to only about 5 per cent under the National Urban Livelihood Mission (NULM) in 2021-22.  IV. Regional Perspective on Microfinance with Special Reference to North-East Another key feature of microfinance, apart from those discussed in the foregoing section, is its regional reach and distribution. Banking in India has been historically characterised by regional imbalances, as examined in the literature and even touched upon later in this section (Shetty, 2005). The regional perspective of microfinance assumes importance, as it is a tool for financial inclusion aimed at meeting the financial needs of the under-served pockets and addressing the existing imbalances in banking. It can be argued that as microfinance is intermediated primarily through banks, the development of banking can influence the development of microfinance. In fact, Sharma (2017) identifies the lopsided development of bank branches as being a reason affecting the development of microfinance in the north-east. However, as the regional analysis in this article relates to the entire ambit of microfinance, provided not just by banks but also by non-bank intermediaries, it can provide useful insights into whether microfinance has indeed served as a tool for financial inclusion. Following are the major stylised facts emerging from the regional assessment of microfinance: Concentration of Microfinance in Eastern and Southern Regions The microfinance portfolio is skewed with the eastern and southern regions together accounting for close to 60 per cent of the total amount of microfinance disbursed and number of activemicrofinance loans in 2021-22 (Table 2).5 Earlier studies had identified the southern region as having the highest concentration of microfinance (Kumarand Golait, 2009).6 However, going by the striking ascent of microfinance in the eastern region in recent years, it can be concluded that this region has emerged as another hub of microfinance. Despite its proximity to the eastern region, the share of the north-east has been in single digits and the lowest among all regions; the region has, in fact, been seen losing its share in recent years. Although useful, shares offer only a cursory insight into the distribution and hence, we construct indicators of access and usage of microfinance. These indicators too bring out the dominance of eastern and southern regions in the coverage of microfinance. To illustrate, almost all districts from the eastern region were covered by microfinance from banks in 2020-21. Similarly, in the southern region too, banks provided microfinance in about 84 per cent of the districts. The coverage of women through SHGs linked to banks through credit was also the highest in the eastern andsouthern regions.7 The usage of microfinance too was the most widespread in the eastern and southern regions. There were two loans reported per every unique borrower in these two regions, indicating higher intensity of microfinance. Reasonable Spread of Microfinance in North-east Based on the indicators of access and usage of microfinance, the penetration of microfinance seemed reasonable in the north-east; it was, of course, much less compared to the eastern and southern regions. Although only about three-fourth of the districts from the north-east were covered by microfinance in 2020- 21, on most indicators of access and usage, the north-east scored reasonably well. To illustrate, per 1000 women, there were 27 saving-linked SHGs as compared to the national average of 18. Furthermore, the region had four credit-linked SHGs per 1000 women, again closer to the national average. On an average, every unique borrower reported two microfinance loans, which was also comparable with the national average. The penetration of microfinance in the central, northern and western regions was relatively weak. The national average for most indicators of access and usage of microfinance was pulled down by these three regions. Microfinance - Partly Instrumental in Addressing Regional Imbalances in Banking If we rank the six regions based on the indicators of banking access and usage, a clear divide emerges between the southern, northern and western regions on the one hand, and the eastern, north-eastern and central regions on the other, with the north-east clearly being the most under-banked region in the country (Table 3).

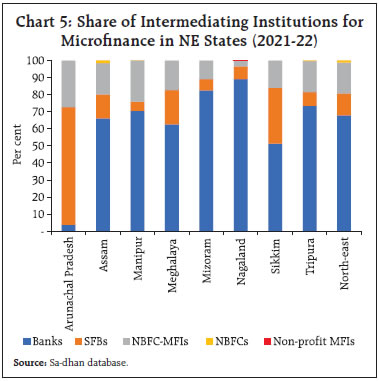

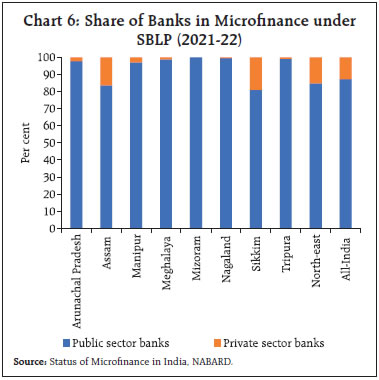

To illustrate, the average population per bank branch, the basic demographic indicator of banking access, was relatively low for the southern, northern, and western regions. By contrast, the eastern, north-eastern and central regions reported a much higher population per branch underlining a weaker density of banking for their population. Even if the population per bank branch for a region is low, it may not always imply easy access if the density of population is low, or the region is marked by hilly and difficult terrains. Hence, we construct the physical indicator of banking access defined as bank branch per 1000 square kilometres. The physical access to banking was the weakest in the north-east, with only 19 branches per 1000 square kilometres in 2020-21. The intensity of bank credit usage captured by credit to net state domestic product (NSDP) ratio was also the lowest for the north-east, at just 24 per cent. The credit to deposit (CD) ratio – another indicator of credit usage – was 43 per cent in the north-east. By contrast, the CD ratio ranged between 70 per cent and 90 per cent in southern, northern and western regions. Juxtaposing the banking and microfinance indicators, it can be inferred that microfinance has been able to make forays into the relatively under-banked regions. This observation is most certainly true for the eastern region, and to an extent, also for the north-east. V. Microfinance in the North-east: Intra-regional Spread The regional analysis in the foregoing section while insightful, can conceal the intra-regional trends, which may be relevant for the policy on financial inclusion. While the north-eastern region shows a reasonable penetration of microfinance, there are commonalities and distinct differences across states within this region in terms of access and usage of microfinance. Some of the intra-regional trends are as follows: Banks - Single-largest Source of Microfinance In all states of the north-east, banks are the most important source of microfinance except Arunachal Pradesh, where SFBs are the most dominant source (Chart 5). SFBs, however, are also banks, although of a differentiated kind. Although banks are the single-largest source of microfinance in the north-east at present, various MFIs, including NBFC-MFIs, have played a role in spreading microfinance in the region in the past. As summarised well in Sharma (2017), while microfinance in the north-east began through SBLP, MFIs emerged as a major source during the 2000s. The concerns that surfaced by the end of 2000s about the lending and recovery practices of certain MFIs from the erstwhile state of Andhra Pradesh shook the microfinance sector across the country (see discussion in Section III). Thisalso included the north-east (ibid.).8 While the hold of MFIs has diminished, banks have sustained their position in microfinance in the north-east. And even as the general access and usage of banking remains plagued by regional imbalances, microfinance has been able to make inroads into an under-banked region like the north-east.  Within banks, it is the public sector banks that are almost entirely responsible for microfinance in all north-eastern states (Chart 6). The involvement of private sector banks remains limited not only in the north-east but also at the all-India level. In 2021-22, private sector banks accounted for only about 13 per cent of the total microfinance under SBLP across India. State-level Differences in the Access and Usage of Microfinance As discussed earlier, the north-east as a whole scores well on most indicators of access and usage of microfinance. However, the development of microfinance is not uniform within the region (Table 4).

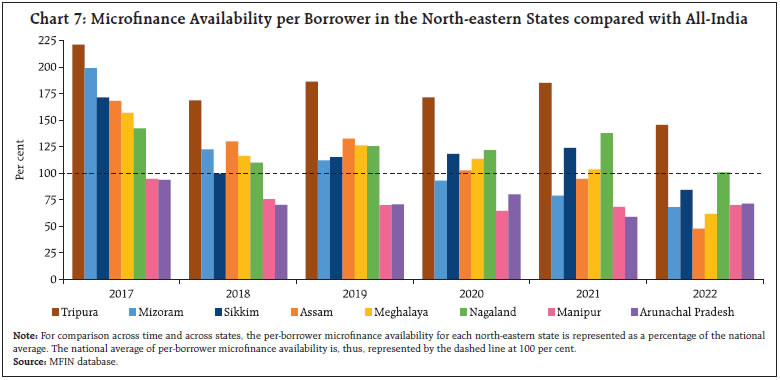

To illustrate, the two states of Tripura and Assamscore high on most indicators of microfinance.9 By contrast, Arunachal Pradesh, the far-eastern state of India, is on the other extreme in penetration of microfinance. The remaining north-eastern states are positioned between these two ends with varying degrees of microfinance access and usage.  Declining Quantum of Microfinance Notwithstanding the variations, it is evident that the relative quantum of microfinance per borrower across all north-eastern states has been on a decline in recent years (Chart 7). While the pandemic and the associated lockdowns starting in March 2020 could have played a role in reducing the per (unique) borrower availability of microfinance, the decline could be seen since the pre-pandemic period. The declining per-borrower availability also corroborates the observation made earlier about a reduced share of the north-east in the total microfinance portfolio in recent years (see Section IV). Microfinance, by its very nature, is focused on socio-economically vulnerable sections, especially women. It has been implemented primarily through regulated financial intermediaries, making it an important facilitator of financial inclusion in India. As part of the nationwide SBLP, banks, particularly public sector banks, have been key stakeholders in microfinance. Over time, NBFC-MFIs and SFBs too have emerged as important intermediaries. In its initial years, microfinance developed in the southern region; it has also spread to other regions over time. It has made significant strides into the eastern region – a region historically under-served by the banking system. In fact, most demographic and geographic indicators of banking access and usage bring out a regional divide even in the contemporary period, with the eastern, north-eastern and central regions emerging as relatively under-banked as compared to the southern, northern and western regions. As microfinance has spread in the eastern region, it has also benefited the neighbouring north-east to an extent. Even though north-east accounts for the smallest share in total microfinance portfolio, it scores reasonably well on most indicators of access and usage of microfinance. At present, microfinance in the north-east is largely from banks, particularly public sector banks. Although the spread seems reasonable for north-east as a whole, the intra-regional trends suggest an uneven development of microfinance. The development has been the highest in Tripura followed by Assam, while Arunachal Pradesh has lagged far behind. The extent of commercial activity, degree of financial/general literacy and institutional capabilities in promoting SHGs may have determined the pace of financial inclusion and adoption of microfinance in thenorth-east.10 The development of finance, however, is shaped not just by economic, social and cultural factors in a given region but also by public policy. There has been a distinct focus by the RBI on the north-east in terms of opening new bank branches/outlets. Going forward, the policy of financial inclusion, including the SBLP, needs to stay focused on the north-east, but more specifically on the states that are relatively under-served by finance from this region. References: Chakrabarty, K C (2011), “Financial Inclusion and Banks – Issues and Perspectives”, Address at the FICCI Seminar, 14 October, New Delhi. Chavan, P (2017), “Public Banks and Financial Intermediation in India: The Phases of Nationalisation, Liberalisation, and Inclusion,” in Christoph Scherrer (ed.), Public Banks in the Age of Financialisation: A Comparative Perspective, Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, Cheltenham. Chavan, P (2020), “Status and Determinants of Banking in the North-Eastern Region: The Case of Tripura” in V K Ramachandran, M Swaminathan and R Basu (eds.) Socio-Economic Surveys of Three Villages in Tripura – A Study of Agrarian Relations, Tulika Books, New Delhi. Kumar, P and R Golait (2009), “Bank Penetration and SHG-Bank Linkage Programme - A Critique”, RBI Occasional Papers, 29(3). Nath, K and L Nochi (2014), “Microfinance in the North-Eastern Region of India - Opportunities and Challenges (Special Focus on Arunachal Pradesh)”, Asian Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, 4(12):104, January. Rao, M R (2021), “Microfinance - Empowering a Billion Dreams”, Address at the Sa-Dhan National Conference on “Revitalizing Financial Inclusion”, October 27. RBI (2011), Report of the Sub-Committee of the Central Board of Directors of Reserve Bank of India to Study Issues and Concerns in the MFI Sector (Chair: Y H Malegam). RBI (2008), Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India – 2007-08, Mumbai. Roy, A (2011), “Microfinance and Rural Development in the North-East India”, http://www.pbr.co.in/2011/2011_month/Jan_March/0006.pdf Sharma, A (2017), Microfinance in the North-eastern Region: Growth and Challenges in Deepak K. Mishra and Vandana Upadhyay (eds.), Rethinking Economic Development in Northeast India, Routledge India. Shetty, S L (2005), “Regional, Sectoral and Functional Distribution of Bank Credit” in V. K. Ramachandran and Madhura Swaminathan (eds.), Financial Liberalisation and Rural Credit, Tulika Books, New Delhi. Sriram, M S (2021), “Financial Inclusion and the Pandemic”, Economic and Political Weekly, 57(20), May. Appendix 1: States/Union Territories under Different Regions

^ The authors are from the Department of Economic and Policy Research. * The authors gratefully acknowledge data support from Sa-dhan and MFIN. Useful discussions with late Shri P. Satish, Sa-dhan are also acknowledged. Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Reserve Bank of India. 1 See RBI Annual Reports for FIP achievements. 2 These concerns related to high interest rates, and multiple loans leading to over-indebtedness of borrowers. The RBI introduced regulations concerning interest rates, annual margins and caps on loan amounts during various cycles, among others, for a better operational discipline among NBFC-MFIs, see “RBI Master Circular - Bank Finance to Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs)” January 5, 2022. 3 Although banks extend microfinance directly to SHGs under SBLP, they may involve other institutions such as non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in the formation and nurturing of SHGs. 4 Microfinance under JLGs is given to (a) those not covered under any SHG or (b) those members of SHGs whose credit needs have increased over time and find it difficult to find other members to provide mutual guarantee for their large-sized loans. The microfinance extended through JLGs is, thus, of a longer term and fulfils credit needs of a larger size as compared to SHGs. Also, under SHGs, microfinance is typically given for group activities, while JLGs involve the provision of microfinance for individual as well as group activities against the social collateral of mutual guarantee. JLGs are being organised in large numbers for tenant farmers, oral lessees and sharecroppers, micro-entrepreneurs, etc. See https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=9336&Mode=0 5 The regional classification broadly follows from Basic Statistical Returns of Scheduled Commercial Banks in India, RBI; See Appendix 1. 6 As against the coverage of only SBLP in Kumar and Golait (2009), the current study has considered the entire ambit of microfinance as provided by Sa-dhan. The study has also compared the MFIN data with the data provided by Sa-dhan for corroboration; the trends are largely comparable. 7 Here, we divide the unique borrowers of microfinance by total women in a given region. As there is no gender-wise break up unique borrowers and women are indeed the key beneficiary of microfinance, we apply the reasonable assumption that all borrowers are women. 8 Sharma (2017) argues that the governmental ban on NGOs (acting as MFIs) in Assam also led to the decline of these institutions in the north-east. 9 For a similar observation, see Nath and Nochi (2014) and Sharma (2017). 10 Chavan (2020) observes that limited commercialisation contributed to limited credit needs in her study area in the north-east. Sharma (2017) identifies the non-availability of competent institutions for promoting SHGs as a factor affecting microfinance in the north-east. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

கடைசியாக புதுப்பிக்கப்பட்ட பக்கம்: