6.1 Commercial banks undertake a wide variety of activities, which play a critical role in the economy of a country. They pool and absorb risks for depositors and provide a stable source of investment and working capital funds to various sectors of the economy. In addition, they provide a smooth functioning payment system that allows financial and real resources to flow relatively freely to their highest return uses. They are also a back up source of liquidity for any sector in the economy in temporar y difficulty. Banks are a particularly important source of funds for small borrowers who often have limited access to other sources of external finance. The three main interrelated functions of commercial banks are holding of deposits; creating credit through lending and investment activities; and providing a mechanism for payments and transfers of funds for various productive activities. The extension of credit or lending is, thus, the principal activity of a commercial bank.

6.2 From the early days of banking theory, the difference between deposits and lending was viewed as minimal, associated with cash balances required to satisfy uncertain cash flows and regulatory seigniorage extracted from the depository process by the central bank through required reserves held in fiat money or central bank balances (Meade, 1934). Not only is lending the primary source of banks’ income, but it provides financing for productive activity throughout the economy. Historically, understanding the role performed by the commercial banks in the economy has had its roots in macroeconomic theory. Keynes (1930) and Pesek and Saving (1967) argued that commercial banks are central to a macro economy as they act as financial intermediaries between savers and investors.

6.3 Banks in India have traditionally been the main source of credit for various sectors of the economy. They have also funded borrowing requirements of the Central and State Governments by investing in their securities. Lending and investment operations of banks in India have evolved in response to the changing needs of the economy. Prior to the initiation of financial sector reforms in the early 1990s, lending by banks was tightly regulated and banks were expected to align their lending operations to plan priorities. Bank lending was the principal focus of monetary policy under the credit planning approach adopted in 1967-68. However, in the wake of banking sector reforms, various restrictions on banks’ balance sheet were withdrawn and direct credit controls largely dismantled, though in a phased manner. Directed investments were also reduced to a significant extent. The system of administered lending rates was also dismantled and various other restrictions on banks’ lending were gradually removed in order to enable banks to operate in a flexible manner. This led to a structural transformation in the lending and investment operations of the banks. Keeping in view their impact on the overall macroeconomic performance of the country, this chapter details the lending and investment operations of banks in India, especially in the light of financial sector liberalisation measures spanning the last decade and a half.

6.4 The chapter is divided into ten sections. Section II begins with a brief review of literature on the theoretical underpinnings of lending operations of banks. It takes a broad overview of the portfolio behaviour of banks and the allocation of assets in terms of loans and investments. Section III focuses on the trends in overall credit of scheduled commercial banks in India. The major indicators of lending behaviour by banks, including the trends in the credit-deposit ratios of banks are analysed. Trends in agricultural lending by banks along with the various issues in lending to agriculture are set out in Section IV. The cross-country patterns in advances to agriculture are also traced in this section to have an insight as to how agricultural lending policies have evolved in different countries. Section V covers the trends in lending to industry with a special focus on lending to the small and medium enterprises (SMEs) sector. This section contains a cross-country analysis of lending to SMEs and explains as to how banks in some countries have overcome the constraints faced by them while lending to SMEs. Section VI analyses the trends in lending by banks to the infrastructure sector. The cross-country experiences in financing infrastructure by banks are also covered. In Section VII, rapid growth of retail loans and various issues concerning thereto are covered. Section VIII analyses the various aspects of investment behaviour of banks. Section IX, as a way forward, makes some suggestions for ensuring adequate and timely credit to various sectors of the economy. Section X sums up the main points of discussions.

II. LENDING OPERATIONS OF BANKS –THEORETICAL UNDERPINNINGS

6.5 The literature available on banking provides various theories which govern the lending operations of banks. These theories have evolved over time along with the evolution of commercial banks. However, most of these theories are based on the conventional distinction between commercial banks as creators and other private financial enterprises as brokers of loanable funds. Commercial banks can borrow at a lower interest rate and lend at higher interest rates. They relieve the market of some primary securities and substitute others’ indirect securities or financial assets whose qualities command a higher price. The margin between yields on primar y and indirect securities is the intermediaries’ compensation for the special services they supply.

6.6 The earliest theory of credit is the commercial loan theory of credit which is also referred to as the ‘real bills doctrine’. This theory, originated in England, dates back to the 18th century. Bank lending to merchants traditionally took the form of discounting of commercial bills. According to this theory, the earning assets of commercial banks must be in the form of short-term, self-liquidating loans extended to businesses for the financing of their inventory needs. It was strongly believed that banks by financing these types of loans could possess most liquid assets which will enable banks to easily meet their demand deposits obligations. In fact, the term ‘commercial bank’ owes its origin to the commercial loan theory as banking was related to the financing of commerce (Roussakis, 1997). Despite certain limitations of this theory, in practice many banks still prefer the short-term self-liquidating loans over other types.

6.7 Another major theory of bank lending is the shiftability theory which holds that a bank’s assets are shiftable, i.e., easily marketable and the liquidity of most of the assets is adequately maintained. For instance, the securities that can be easily converted into cash, possess a high degree of liquidity. In essence, the shiftability theory is based on the consideration of ‘how quickly’ the assets could be converted into cash. This theory was first set forth by H.G.Moultan in 1918. Commercial banks all over the world that hold stocks of sovereign bonds, which in present day banking is a common practice, are knowingly or unknowingly followers of this doctrine.

6.8 According to anticipated income theory (Prochnow,1949), a bank can maintain its liquidity if loan repayments are scheduled on the basis of the anticipated income of the borrower rather than the use made of the funds or the collateral offered. The basic argument of this theory is that the banks should rely on the borrower’s income earning capacity or the cash flow and the coverage of debt service requirements, rather than merely on the collateral. The debt service coverage is determined on the basis of inclusive cash-flow projections which ordinarily provide a reliable indication of the quality of the loan being financed. This theory seems to be more suitable in the practice of the modern time banking than the previous two theories.

6.9 According to the liability management theory, it is not necessary for a bank to observe traditional liquidity standards if it can go into the market and bid for funds whenever it is in need of liquidity. A bank can create additional liabilities to meet its liquidity requirements, and banks have a number of avenues to meet their liquidity requirements such as issuing CDs, borrowing from the central bank and borrowing in the capital market, among others. The liability management theory is a major breakthrough in the modern approach to commercial banking.

6.10 Banks lending operations are determined, at the micro level, based on certain considerations outlined in the theories discussed above. However, the quantum and target group of lending is determined by the financial system which a country adopts, i.e., market based financial system or bank based financial system. An important aspect of the growth process that has been widely discussed in the available literature on the subject is the type of financial system that is the most conducive to growth. Focusing from this standpoint, most of the systems of industrial finance can be grouped into two clear systems mentioned earlier. At one end is the ‘market-based finance’, where financial markets play a more important role than the banking industry. At the other end of the spectrum is the model of ‘bank-based finance’, in which savings flow to their productive uses predominantly through financial intermediaries such as banks and other financial institutions, and the capital market is less important for raising funds. Most of the industrial financing systems have evolved endogenously from their own particular circumstances of economic history - and have their own success story to tell or otherwise. The market-based system is relatively impersonal because the sources of funds could actually be atomistic household savers, directly or indirectly through mutual funds, pension funds or insurance funds. The bank-based systems are more relationship-based, because the lenders are few and large. Bank-based systems tend to be stronger in countries where the Governments have taken a direct role in industrial development such as Germany in the 19th century, and Japan, East Asia, South-East Asia, China and India, in the 20th century (Mohan, 2004).

6.11 Ever since India opted for development plans for its growth, the role and importance of banking and other financial institutions have gained in importance. Research has also confirmed the inter-linkage between finance and growth in India. The Indian growth process has, essentially been ‘finance-led’, whereby expansion in the financial sector played an enabling role in promoting capital accumulation, which, in turn, engendered higher growth (Reddy, 2006).

Portfolio Behaviour of Banks

6.12 Commercial banks hold a portfolio of assets and, given the characteristics and distribution of the liabilities, they attempt to structure their portfolio of assets in such a manner so as to yield the greatest return, subject to the constraints. Banks have four categories of assets, viz., cash in hand and balances with the central bank; assets with the banking system; investments in Government and other approved securities; and loans and advances. Quantitatively, lending and investments are the most important earning assets of banks. The quantum and also the composition of loans and investment is determined by the banks’ portfolio behaviour which, in turn, is generally determined by the present and expected levels of market interest rates, loan demand and cash demand and actions of the central banks. The study of commercial bank portfolio behaviour is important as it is a significant explanatory factor for the magnitudes and changes in the bank credit as well as the cost and flow of credit to specific sectors of the economy.

Determinants of Bank Lending

6.13 Literature sets for th divergent views regarding the determinants of bank lending. According to one view it is the demand side elements that determine the bank lending whereas the other view professes the dominance of supply side factors. The principle that the demand for bank loans determines bank portfolio behaviour is sometimes referred to as the accommodation principle. Similarly the principle that commercial banks’ responses to market forces determine their portfolio behaviour is referred to as profit maximisation principle. As per accommodation principle, bank lending is the key determinant of banks’ portfolio behaviour. The use of the term “accommodation” implies that the demandfor such loans would mainly determine bank behaviour regarding borrowing from the central bank, holdings of excess reserves, and the division of earning assets between loans and investments. Thus, the response of demand for loans to such economic variables as interest rates and economic activity would also determine bank behaviour regarding the above mentioned balance sheet accounts (Boyd and Gertler, 1993). Under the accommodation principle, bank behaviour would mainly reflect the demand of customers for loans. For example, a rise in the demand for loans from banks (supply of this form of earning asset) would be met, subject to the deposit constraint, by reductions in investments and excess reserves and an increase in borrowings from the central bank and, with banks being the mainstay of financial intermediation, the banking sector.

6.14 The profit maximisation principle implies that commercial banks’ responses to market forces determine their portfolio behaviour. If the existing distribution of assets held by the commercial bank is not the distribution desired, then the bank will attempt to adjust its portfolio of assets by increasing its holdings of some assets and decreasing its holdings of other assets. The commercial bank’s decision of allocating its portfolio of assets between the two earning assets, i.e., loans and investment are generally determined by the existing legal reserve requirements against commercial banks’ demand and time deposits. Given the de jure and de facto status of the most of banks’ liabilities, and given that an individual bank cannot predict with certainty future deposit flows, loan demands, interest rates, and actions by the monetary authorities, commercial banks desire to have a portion of their asset portfolio that represents a stock of liquidity to act as a buffer against changes in the aforesaid factors. In practice, the dominance of either demand or supply side on credit fluctuations is difficult to prove as both the factors play a determining role most of the times.

6.15 According to one view, the firms’ and households’ demandis the underlying determinant of bank credit. As per this view, the credit extended by the institutions adjusts in consonance with the demand conditions prevalent at that point of time. Cottarelli et al., (2003) put forth the view that the recent lending boom in central and eastern Europe owes its origin to an upward shift in the IS supply curve in the region following macroeconomic deregulation. Similarly, the collapse of bank lending in East Asia following the 1997-98 financial crises was led by a decline in the demand for bank loans rather than banks’ withdrawal from the credit market (Ghosh and Ghosh, 1999).

6.16 The real business cycle literature also sets forth the view that the demand for bank loans is highly procyclical. An analysis of several episodes of consumption boom in industrial and developing economies revealed that these owed their origin to consumption boom originating in terms-of-trade improvement. A positive technological shock with the resultant increase in investment and credit demand in the economy could also be one of the factors. Montiel (2000) after examining several episodes of consumption boom in industrial and developing economies between 1960 and 1995, concluded that in most of the countries, terms-of-trade improvements led to consumption boom which subsequently resulted in sharp pick up in lending by banks.

6.17 An alternative view is that fluctuations in bank lending reflect supply side developments such as changes in banks’ capacity and willingness to lend. To the extent that some firms face a high external premium in accessing the capital market, or such markets are not well developed, they are heavily dependent on bank lending. Others have argued that bank credit is, indeed, special because it could trigger innovation, particularly in industries that did not have access to external financing; (Rajan and Zingales, 1998). Thus, any shock that relaxes banks’ lending capacity - a rise in capital inflows or an easier monetary policy - could lead to increased credit supply in the economy. Moreover, such shocks could affect asset prices and balance sheets, exerting an indirect influence on banks’ capacity to lend (Mohanty et al., 2006).

6.18 Financial liberalisation in the face of poorly regulated and supervised banks and inappropriate incentive structures may also lead to increased boom and bust credit cycles in emerging economies (Hernández and Landerretche, 2002; Barth et al., 2002). Credit booms have often been preceded by strong capital flows and overheating of asset prices. However, when asset prices collapse, the banks’ non-performing assets rise. The banks become risk averse leading to a credit crunch as banks reduce their lending. The access to bank lending is also determined by the level of concentration of bank lending, regulatory regime in place and presence of foreign banks. The level of capital held by the bank also determines the willingness of the bank to support new loan proposals (Bernanke and Lown, 1991).

6.19 According to some recent studies, creditors’ rights and emergence of credit information bureaus in the emerging economies also create an enabling environment for improved lending by banks. The basic argument is that countries with better private property rights and credit risk screening mechanisms (particularly well functioning credit bureaus or credit registery systems) are able to achieve a higher credit to GDP ratio than those that lack such institutions (Mohanty et al., 2006).

6.20 To sum up, different theories have evolved from time to time to explain banks’ lending behaviour. According to the commercial loan theory, which is the earliest theory on credit, the earning assets of banks will be in the form of short-term and self-liquidating loans. According to the shiftability theory, the main consideration is how quickly the assets can be converted into cash. The anticipated income theory postulates that a bank can maintain its liquidity if loan repayments are scheduled on the basis of the anticipated income of the borrower. According to the liability management theory, it is not necessary for a bank to observe traditional liquidity standards if it can go into the market and bid for funds whenever it is in need of liquidity. Banks’ lending operations are determined at the micro level, based on certain considerations as suggested by the theories. However, the overall quantum and target group of lending is determined by the financial system which a country adopts, i.e., market based financial system or bank based financial system.

6.21 Bank lending is determined by both supply side and demand side factors. On the supply side, banks’ portfolio behaviour determines their lending. Commercial banks hold a portfolio of assets based on risk return perceptions and distribution of the liabilities so as to yield the greatest return. Loans and investments are the two most important earning assets in the asset portfolio of banks and their composition is determined by the banks’ portfolio behaviour which, in turn, is based on either accommodation principle where lending is the key determinant of banks’ portfolio or profit maximisation principle. A rise in capital inflows or an easier monetary policy could also lead to increased credit supply in the economy. Banks’ willingness to lend could also be affected by the regulatory regime in place, and whether they hold enough capital to support all the new profitable loan proposals.

III. LENDING OPERATIONS OF SCHEDULED

COMMERCIAL BANKS IN INDIA

Policy Developments

6.22 In India, prior to initiation of financial sector reforms in the early 1990s, the lending operations of the banking sector were highly regulated. These related to an administered structure of interest rates, high levels of pre-emptions in the form of reserve requirements, and credit allocation to certain sectors. There existed different credit limits and margin requirements in respect of sensitive commodities and sectors. There were requirements of prior approval from the Reserve Bank for sanction of credit beyond a threshold. Commercial banks were also required to meet mainly the short-term/working capital funds requirements. As such, banks did not have much choice in terms of allocation of resources among different asset classes.

6.23 The initiation of financial sector reforms facilitated a gradual move away from a financially repressed regime to a liberalised one. Banks were given the freedom to innovate and expand their businesses. Lending rates were freed to enable banks to price their products freely. Interest rate deregulation imparted greater efficiency to the resource allocation process (Box VI.1). The objective of the banking sector reforms was to promote a diversified, efficient and competitive financial system with the ultimate objective of improving the allocative efficiency of resources through operational flexibility, improved financial viability and institutional strengthening (Mohan, 2005). With the phasing out of the regulated regime, banks started exploring new avenues for expanding businesses.

Box VI.1

Lending Operations of Banks: Major Policy Initiatives

Since the early 1990s, several policy measures have been initiated to provide flexibility to banks in their lending and investment operations.

Lending Interest Rates

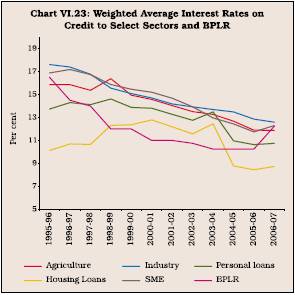

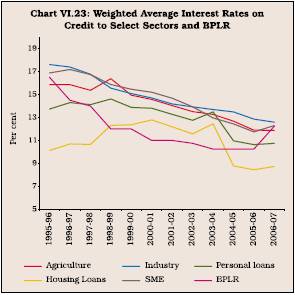

Lending interest rates of commercial banks were deregulated in October 1994 and banks were required to announce their prime lending rates (PLRs). The concept of benchmark prime lending rate (BPLR) was introduced by the Reserve Bank on April 29, 2003 to address the need for transparency in banks’ lending rates as also to reduce the complexity involved in pricing of loans. Banks are now free to prescribe respective BPLRs. Banks are also permitted to offer floating rate loan products linked to a market benchmark in a transparent manner.

Term-lending by Banks

Various restrictions on term loans by banks were gradually phased out by 1997. In terms of the guidelines prevailing before the initiation of economic reforms in 1991, banks were expected to extend term loans for small projects in participation with the State level institutions, though it was not mandatory. For large projects, however, they were allowed to participate compulsorily along with all-India financial institutions (FIs), subject to the condition that the share of the banking system would be restricted to 25 per cent of term loan assistance from banks and FIs and the aggregate term finance from the banking system could not exceed Rs.75 crore.

Exposure Limits

Regulatory limits on banks’ exposure to individual and group borrowers in India were prescribed to avoid concentration of credit. The applicable limit is 15 per cent of capital funds in the case of a single borrower and 40 per cent in the case of a group of borrowers. Credit exposure to borrowers belonging to a group may exceed the exposure norm of 40 per cent of bank’s capital funds by an additional 10 per cent (i.e., up to 50 per cent), provided the additional credit exposure is on account of extension of credit to infrastructure projects. Credit exposure to a single borrower may exceed the exposure norm of 15 per cent of bank’s capital funds by an additional 5 per cent (i.e., up to 20 per cent). In addition, banks may, in exceptional circumstances, with the approval of their boards, consider enhancement of the exposure to a borrower up to a further 5 per cent of capital funds.

Priority Sector Lending

Over the years the stipulation for lending to the priority sector has been retained, though its scope and definition was fine-tuned by including new items. Based on the recommendations of the Working Group, set up by the Reserve Bank, the priority sector norms were revised in April 2007. As per the revised norms, the sectors of the society/economy that impact large segments of the population, the weaker sections and the sectors which are employment-intensive such as agriculture and micro and small enterprises, have been retained as priority sector in the revised guidelines, which came into effect from April 30, 2007. Agriculture, small enterprise, micro credit, retail trade, education loans and housing loans up to Rs.20 lakh are the broad categories included in the priority sector.

NPA Management

The high level of non-performing loans (NPLs) of banks, apart from limiting the ability of credit institutions to recycle their funds, also weakened them by adversely affecting their profitability. The Reserve Bank and the Central Government, therefore, initiated several institutional measures to recover the past dues to banks and FIs and reduce the NPAs. These were Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs), Lok Adalats (people’s courts), Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) and the Corporate Debt Restructuring (CDR) mechanism. Settlement Advisory Committees have also been formed at regional and head office levels of commercial banks. Furthermore, banks can also issue notices under the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest (SARFAESI) Act, 2002 for enforcement of security interest without intervention of courts. Further, banks, (excluding securitisation companies/ reconstruction companies) have been permitted to undertake sale/purchase of NPAs. Thus, banks and other credit institutions have been given a menu of options to resolve their NPA problems.

Development of Securitisation Market

With a view to ensuring healthy development of the securitisation market, the Reserve Bank issued guidelines on securitisation of standard assets on February 1, 2006 to banks, financial institutions and non-banking financial companies.

Credit Information Bureau

Comprehensive credit information, which provides details pertaining to credit facilities already availed of by a borrower as well as his repayment track record, is critical for the smooth operations of the credit market. Lack of credit history is an important factor affecting the credit flow to relatively less creditworthy borrowers. In the absence of credit history, pricing of credit can be arbitary, the perceived credit risk can be higher and there can be adverse selection and moral hazard. Accordingly, a scheme for disclosure of information regarding defaulting borrowers of banks and financial institutions was introduced in 1994. In order to facilitate sharing of information relating to credit matters, a Credit Information Bureau (India) Limited (CIBIL) was set up in 2000, which took over the functions of dissemination of information relating to defaulting borrowers from the Reserve Bank. The Credit Information Companies (Regulation) Act was enacted in 2005 to facilitate the setting up of credit information companies.

Statutory Liquidity Ratio Provisions

At present, all scheduled commercial banks are required to maintain a uniform Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) of 25 per cent of net demand and time liability as on the last Friday of the second preceding fortnight under Section 24 of the BR Act. The assets eligible for meeting the Statutory Liquidity Ratio requirements can be held in the form of cash, gold or in unencumbered approved securities. Consequent upon the amendment to Section 24 of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949, the floor rate of 25 per cent for the SLR has been removed and the Reserve Bank has also been empowered to determine the SLR eligible assets. However, no change has been made in the SLR so far in view of the prevailing macroeconomic and monetary conditions.

6.24 Diversification of por tfolios and asset adjustments by banks are now made more on the basis of risk-return considerations. Banks in India followed the accommodation principle in the pre-liberalisaton phase. However, the profit maximising principle has been dominating the banks’ portfolio behaviour in the post-liberalisation phase.

Trends in the Lending Operations of Scheduled Commercial Banks

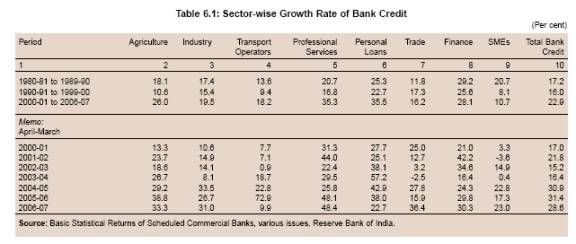

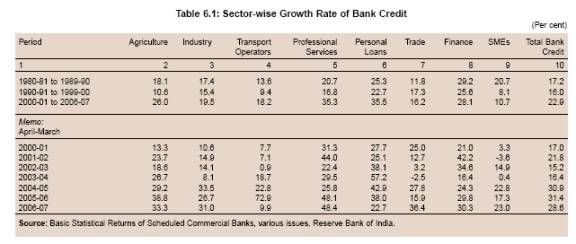

6.25 In India, like many other emerging market economies, commercial banks remain the most important source of credit supply. The total credit extended by scheduled commercial banks grew at 17.2 per cent during the 1980s and 16.0 per cent during the 1990s (Table 6.1).

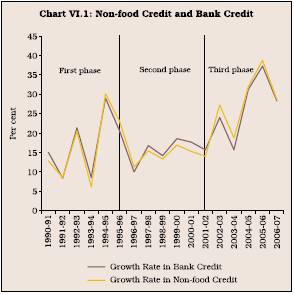

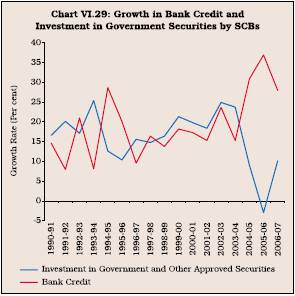

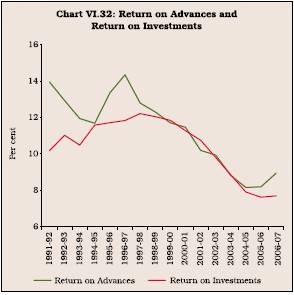

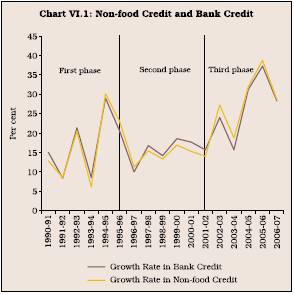

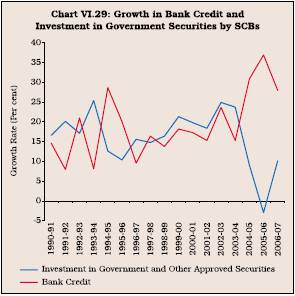

6.26 Credit by scheduled commercial banks from the early 1990s witnessed three distinct phases. In the first phase (from 1990-91 to 1995-96), bank credit growth showed erratic behaviour with the growth rate varying between 8 per cent and 29 per cent. In the second phase (from 1996-97 to 2001-02), bank credit growth decelerated sharply and ranged between 10 and 18 per cent. In the third phase (from 2002-03 to 2006-07) credit growth generally remained high (Chart VI.1).

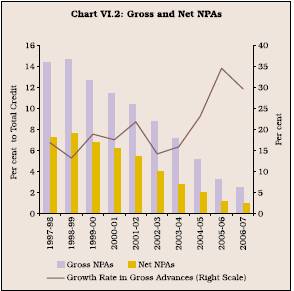

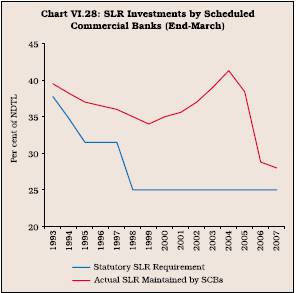

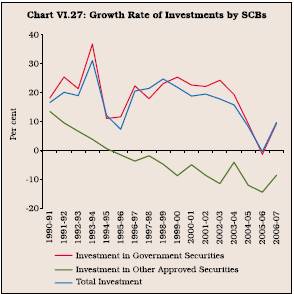

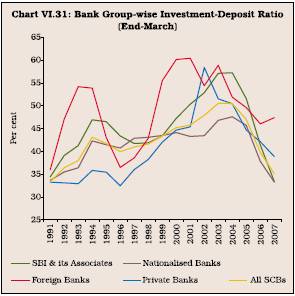

6.27 The deceleration in credit during the second phase was on account of several factors, both on the demand and the supply sides. On the supply side, introduction of prudential norms relating to income recognition, asset classification and provisioning in the early 1990s made banks cautious. Application of norms revealed large gross non-performing assets (NPAs) with scheduled commercial banks (15.7 per cent of their gross advances at end-March 1997). Banks, therefore, became wary of enlarging their loan portfolio. Regression analysis suggests that asset quality is one of the main determining factors of credit, besides time deposits and lending interest rate1. The relatively high level of NPAs, in particular, had a severe impact on weak banks. Banks’ capacity to extend credit was also impaired due to little headroom available in the capital adequacy ratio (8.7 per cent at end-March 1996). Banks found risk adjusted returns on

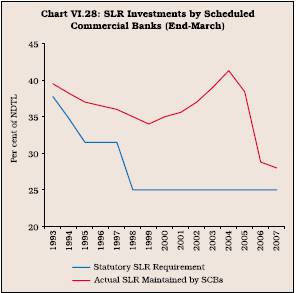

Government securities more attractive. Hence, despite lowering of statutory pre-emption in the form of SLR, banks continued to invest in Government securities, far in excess of the stipulated requirements. Banks’ investments in SLR securities at end-March 1996 were 36.9 per cent of net demand and time liabilities (NDTL) as against the prescribed requirement of 31.5 per cent. Banks’ investments in SLR securities remained more or less at that level (36.7 per cent) by end-March 2002, even as the SLR was brought down significantly to 25 per cent (RBI, 2007a).

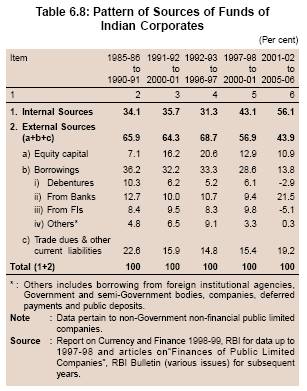

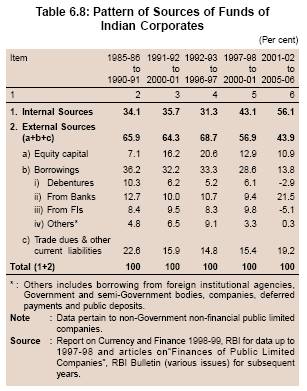

6.28 On the demand side also, several factors contributed to the decline in demand for credit by the corporate sector. The industrial sector witnessed massive expansion in capacity in certain sectors, especially cement and steel, in the initial phase of reforms. However, as the quantitative restrictions were removed and import tariffs reduced, the corporate sector faced intense competition during the latter part of the 1990s. The focus of the corporate sector, thus, shifted from expanding capacity to restructuring and the industrial sector slowed down significantly. The average annual growth rate of industrial production was 5.2 per cent during 1996-97 to 2001-02 as compared with 9.4 per cent in the preceding three years. This affected the demand for credit by the corporate sector. Increased competition also forced corporates to restructure their balance sheets, whereby they increased their reliance on retained earnings and reduced their borrowings. This was evident from the debt-equity ratio, which declined from an average of 85.5 per cent during 1990-91 to 1994-95 to 65.2 per cent during 1995-96 to 1999-2000 (RBI, 2007a).

6.29 Although the Reserve Bank pursued accommodative monetary policy during this period (1996-97 to 2001-02) by reducing the cash reserve ratio (CRR) and the policy rates, viz., the Bank Rate and the reverse repo rate (the then repo rate), credit offtake did not pick up. Downward stickiness of nominal interest rates on the one hand, and the falling inflation rate on the other, led to a significant rise in real interest rates. The average real lending rates of banks increased to 12.5 per cent during 1996-97 to 2001-02 as against 6.5 per cent during 1990-91 to 1995-96 (Mohan, 2003). This also appeared to have contributed to slackness in credit expansion.

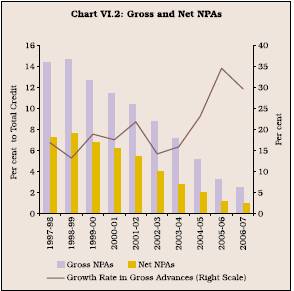

6.30 In the third phase (2002-03 to 2006-07), credit growth generally remained high. The nature of rapid credit growth from May 2002 has been structurally at variance from the historical trends. Credit, in particular, expanded at a robust pace of around 30 per cent for three consecutive years from 2004-05 to 2006-07. The credit expansion was also pro-cyclical in nature, which indicates that the strong income growth recorded in recent years also significantly contributed to credit growth (RBI, 2007a). One of the major contributory factors was an improvement in asset quality. As banks’ gross/net NPAs declined to more reasonable levels, credit growth accelerated (Chart VI.2).

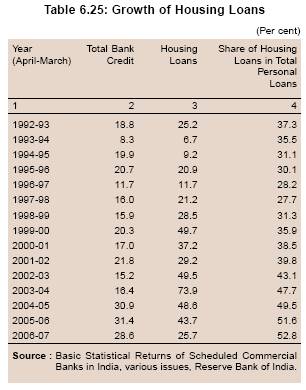

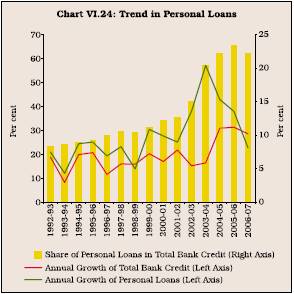

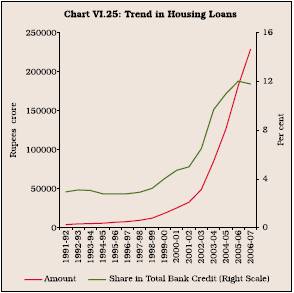

6.31 Other major factors that contributed to the acceleration in credit growth were a pick-up in economic growth, moderation in inflation and inflation expectations, decline in real interest rates, rising income of households and increased competition with the entry of new private sector banks. Besides, the sharp growth in bank credit in recent years could also be attributed to factors such as financial deepening from a low base, structural shifts in supply elasticities, rise in efficiency of credit markets and policy initiatives to improve the flow of credit to sectors such as agriculture and small and medium enterprises. During this phase, retail credit, especially housing loans, emerged as the major source of credit demand as explained in Section

VII. Banks also increased their exposure to the infrastructure sector as detailed in Section VI.

6.32 The rise in the credit to GDP ratio indicates increasing financial deepening. However, rapid credit growth may pose certain risks. In view of rapid credit expansion, the Reserve Bank in April 2006 indicated that growth of non-food bank credit, including investments in bonds/debentures/shares of public sector undertakings and private corporate sector and commercial paper, would be calibrated to decelerate to around 20 per cent during 2006-07 from a growth of above 30 per cent. Keeping this in view, monetary measures were initiated to moderate the credit growth. Besides, prudential measures were also introduced in the form of increased risk weight and provisioning requirement for lending to certain sensitive sectors. The risk weight on exposures on commercial real estate was increased from 100 per cent to 125 per cent and further to 150 per cent. Banks’ total exposure to venture capital funds was included as part of their capital market exposure and they were required to assign a risk weight of 150 per cent to such exposures. The general provisioning requirement on standard advances to the sectors comprising real estate, outstanding credit card receivables, loans and advances qualifying as capital market exposure and personal loans, excluding residential housing loans, was raised to 2.00 per cent on January 31, 2007. The provisioning requirement in respect of residential housing loan was raised to 1.00 per cent from the existing 0.4 per cent for loans in excess of Rs.20 lakh. Monetary measures included an increase in the repo rate by 150 basis points in stages to 7.50 per cent by March 2007 from 6.00 per cent in September 2004. Further, CRR was raised by 150 basis points in stages from 4.50 per cent in March 2004 to 6.00 per cent by March 20072. The Reserve Bank increased the provisioning requirement for banks’ exposure in the standard asset category to systemically important NBFCs to 2.00 per cent from the earlier level of 0.4 per cent. Further, risk weight for banks’ exposure to such NBFCs was increased to 125 per cent from the earlier level of 100 per cent. Banks were prohibited from granting fresh loans in excess of Rs.20 lakh against the NR(E)RA and FCNR(B) deposits, either to depositors or to third parties.

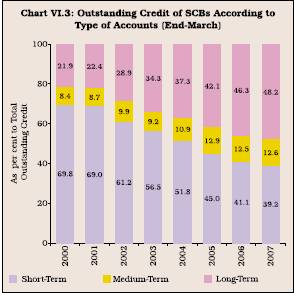

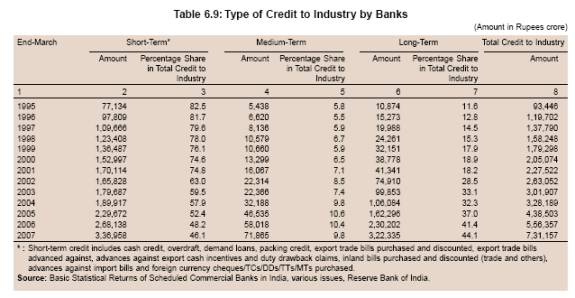

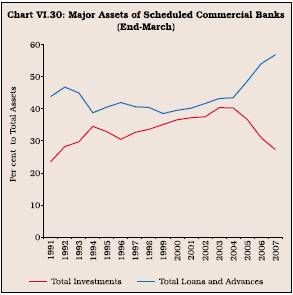

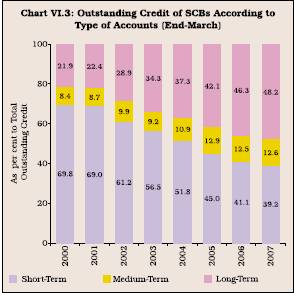

6.33 Housing loans combined with infrastructure financing led to a sharp increase in the share of medium and long-term loans in total credit (Chart VI.3).

The share of long-term loans in the outstanding credit of scheduled commercial banks increased from 21.9 per cent at end-March 2000 to 34.3 per cent at end-March 2003 and further to 48.2 per cent at end-March 2007. The share of medium-term loans also showed an increase from 8.4 per cent in 2000 to 12.6 per cent in 2007.

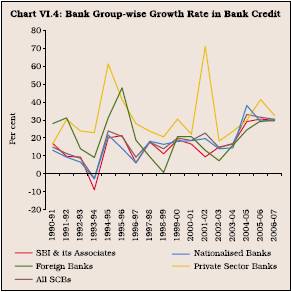

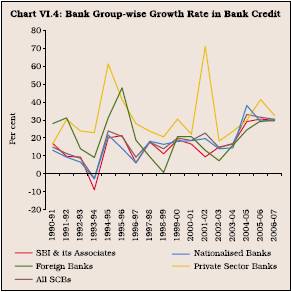

6.34 Bank group-wise analysis indicates that credit growth of private sector banks was consistently above the overall credit growth. At times, it also showed wide variations (Chart VI.4)

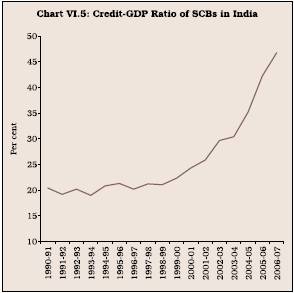

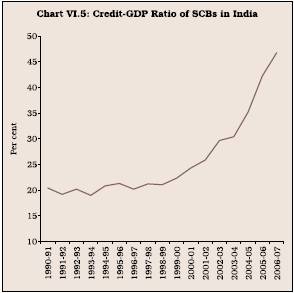

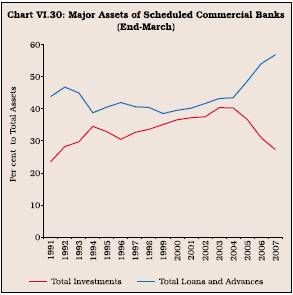

6.35 Bank credit (outstanding), which constituted 20.4 per cent of GDP at end-March 1991, increased to 22.3 per cent at end-March 2000 and 46.8 per cent at end-March 2007 (Chart VI.5).

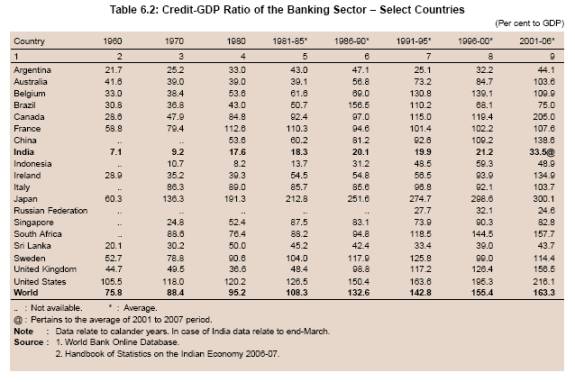

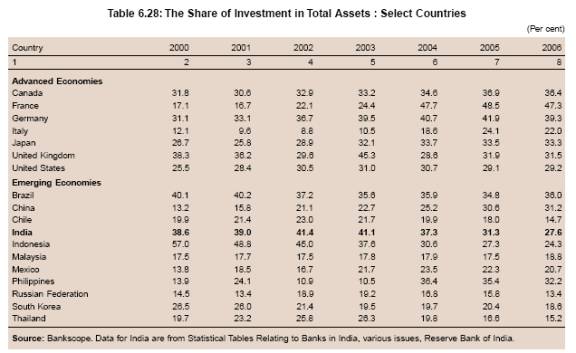

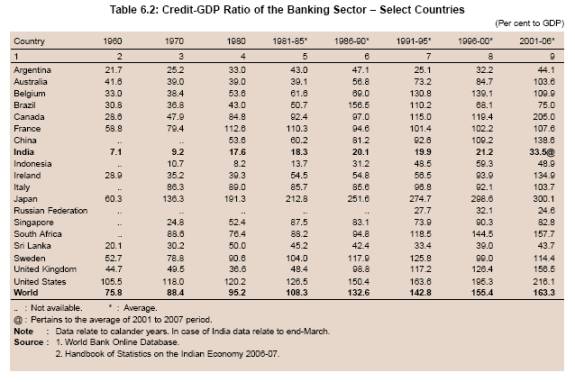

6.36 Notwithstanding the increase, the credit to GDP ratio in India was lower than that of developed and several emerging market economies (Table 6.2).

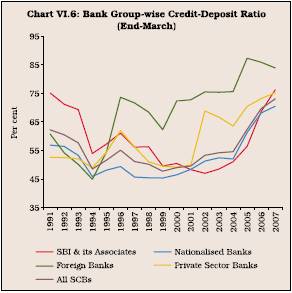

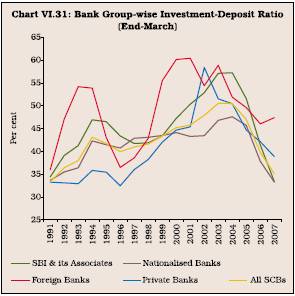

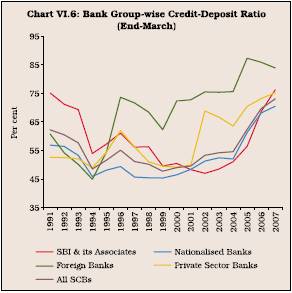

Credit-Deposit Ratio (CDR)

6.37 The credit-deposit ratio refers to the proportion of loan assets funded by banks from deposits mobilised. The C-D ratio of scheduled commercial banks tended to move upwards from 2000-01. The ratio, which was 48.4 per cent at end-March 1994, increased to 53.2 per cent at end-March 2002 and further to 73.0 per cent at end-March 2007. The financing of higher proportion of credit in recent years in a way was facilitated by excess SLR securities portfolio built-up by banks in the mid-1990s. An analysis of bank-group wise credit-deposit ratio during the period 1991-2007 reveals that the credit-deposit ratio of all bank groups tended to move up in line with the increase in overall credit from 2001-02. The ratio of various bank groups almost converged at around 73 per cent at end-March 2007, barring foreign bank group, which maintained significantly higher C-D ratio from 1995-96 than other bank groups. The ratio in respect of foreign banks was at around 84 per cent at end-March 2007 (Chart VI.6).

Sectoral Deployment of Credit

6.38 Economic refor ms and the evolving economic structure had a profound impact on the bank lending to the various sectors of the economy during the 1990s and the current decade. The growth of lending to agriculture by banks during the 1990s slowed down to almost one-half as compared with the 1980s. However, credit growth to agriculture picked up significantly from 2003-04 onwards as a result of concerted efforts made by the Reserve Bank and the Government to increase the flow of credit to agriculture. Bank lending to the industrial sector too slowed down, albeit marginally, in the 1990s. However, it picked up in the current decade. Credit growth to the household sector accelerated sharply in the current decade (refer Table 6.1).

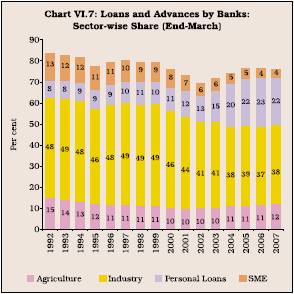

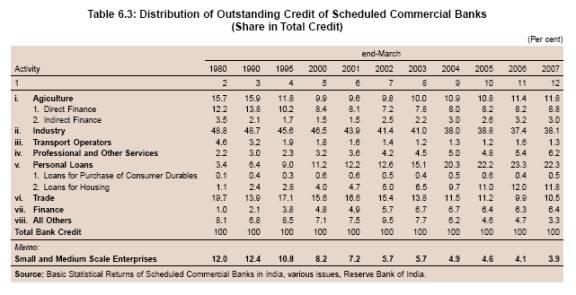

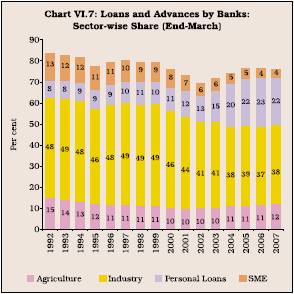

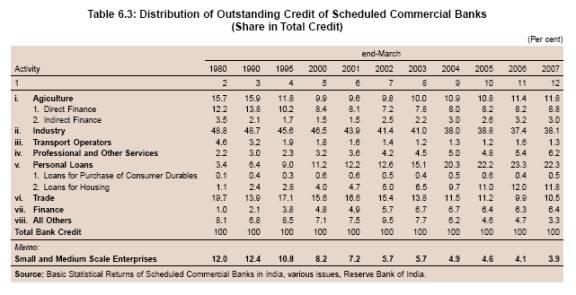

6.39 The share of personal loans in overall credit extended by SCBs increased from 6.4 per cent at end-March 1990 to 22.3 per cent at end-March 2007 (Chart VI.7 and Table 6.3). As a result, other components of credit underwent a significant change. The share of theagriculture sector in bank credit declined in the 1990s before it recovered from end-March 2002 onwards. The share of the industry and the SME sectors also declined. A detailed analysis of bank credit to various sectors is set out in the following sections.

IV. LENDING TO AGRICULTURE

6.40 The key driver for the progress of any sector is the availability of adequate credit. In the case of agriculture, it is not only the availability of credit but also the access to adequate institutional credit that matters, since most of those who are engaged in agriculture belong to the marginal and small farmer categories. In view of this, the strategy has been to strengthen the role of institutional sources of credit

to agriculture with a view to replace informal sources of credit such as moneylenders and ensuring timely credit to the agricultural sector. Moreover, since agriculture still continues to depend on the monsoon (as evident in substantial year to year variations in agricultural output), it is perceived as a high risk area (Box VI.2).

6.41 There was a perceived reluctance on the part of the banks to service high-risk activities, including agriculture. Some policy intervention was thus felt necessary to direct credit to the agricultural sector. The policy framework of agricultural finance has evolved over the years with the aim of creating an enabling environment for the smooth flow of resources to agriculture. The need for adequate institutional credit to agriculture occupied the policy space as early as 1936 and 1937 when studies showed that finance to agriculture was totally dependent on moneylenders and co-operatives and other agencies played a negligible part. Hence, during the period between 1935 and 1950, the focus of the Reserve Bank was on re-invigorating the co-operative credit movement. The increased role for commercial banks in the delivery of rural credit in national policy began as a result of the recommendations of the All India Rural Credit Review Committee set up by the Reserve Bank in July 1966 (Chairman: Shri B Venkatappiah). The role of commercial banks was further widened following the nationalisation of major commercial banks in 1969 (and in 1980) and with the introduction of the concept of priority sector advances in 1969, which was formalised in 1972 (Box VI.3). In terms of recommendations of the Working Group on Rural Banks (Chairman: Shri M Narasimham), regional rural banks (RRBs) were set up constituting the third institutional tier in the “multi-agency approach”. Following the recommendations of the Committee to Review Arrangements for Institutional Credit for Agriculture and Rural Development, a specialised institution, National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) was set up in 1982. It took over the entire undertaking of the Agricultural Refinance and Development Corporation (ARDC) and the refinancing functions of the Reserve Bank in relation to State co-operatives and RRBs.

Box VI.2

Risks Associated with Lending to Agriculture

The nature of risk and its intensity faced by farmers and rural entrepreneurs vary according to the type of farming system, agricultural production, weather conditions and the prevailing economic and agricultural policies. The risks that the financial institutions face while lending to agriculture relate mainly to high interest and liquidity risk, refinance risk and credit risk.

Credit riskincreases in long-term agricultural lending, since estimation of prices, costs, market demand and technical progress becomes more difficult over longer time horizons and the likelihood of systemic risk increases. Accordingly, the margin of error inherent in loan appraisal increases proportionately to loan maturity. There is also the case of larger amounts and longer terms, which result in increasing the moral hazard risks.

Any defaults on term loans have a greater impact on the quality of portfolio of the lender. This may lead to higher costs for loan loss provisioning and affect the rating of the bank in the capital market, increasing the costs of funds. In order to contain portfolio risks, lenders are constrained to limit the share of agricultural term loans in their portfolio. The severity of this risk is more if instruments for managing systemic risks such as crop insurance, irrigation or price risk management tools are absent.

A conventional bank practice that protects the lender against possible borrower default is the requirement of loan collateral such as real estate or mortgage. Banks use loan collateral in order to screen potential clients (as a substitute for lack of customer information) and to enforce and foreclose loan contracts in the event of loan default. The preferred form of conventional bank collateral is mortgage on real property, which, however, requires clear land titles and mortgage registration. As there is generally lack of clear and secure land titles, banks face additional risk in lending to agriculture.

Lending to agriculture tends to be heavily dependent on a very narrow range of sub-sectors with bulk of the portfolios restricted to 2-3 agricultural products in any given branch. The more concentrated the portfolio is among fewer agricultural products, the more susceptible the entire portfolio to market risk and changes in the industry. Moreover, as economic activities of rural depositors are similar or interlinked, the ‘production risks’ tend to be covariant in a given community and might be passed on to the deposit-taking institution. For instance, in the event of any major crop failure and animal diseases among others, the lending institution is beset with the higher risks of massive deposit withdrawals simultaneously with higher loan demand.

One of the most common risks faced by the agriculture sector in developing countries is the vulnerability of the prices of the final products to macroeconomic factors in the rest of the world than the market for the goods and services of urban enterprises, which tend to have local markets that are less volatile, even if they are weak.

The presence of higher risks assumes criticality in lending to agriculture. It is held that experiments with crop or credit-insurance have not been very satisfactory in most of the developing countries so far. In fact, many farmers feel that where compulsory insurance is resorted to, it has only increased the burden of borrowing from institutional sources and once the transaction costs are added, the overall costs rise significantly. Perhaps, it is necessary to recognise that if some elements of insurance are ab initio not viable, extending credit becomes more risky and hence constrained (Reddy, 2005).

References:

Coffey, Elizabeth. 1998. “Agricultural Finance: Getting the Policies Right.” Agricultural Finance Revisited No.2, FAO, June.

Gichler, Thorsten. 1999. “Sources of Funds for Agricultural Lending.” Agricultural Finance Revisited No.4, FAO, December.

Reddy, Y.V. 2005. “Banking Sector Reforms in India: An Overview.” RBI Bulletin, June.

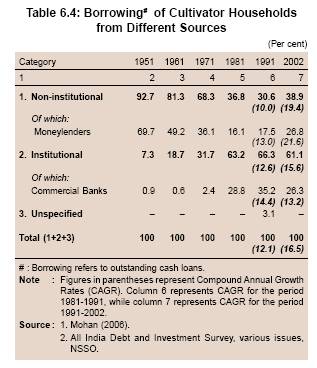

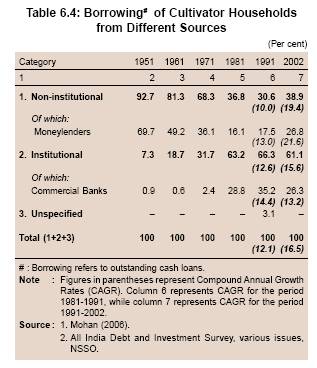

6.42 Institutional credit to cultivator households has made considerable progress since the mid-1960s. Based on the All India Debt and Investment Surveys (AIDIS) by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO), the share of borrowings of cultivator households from institutional sources increased from 7.3 per cent in 1951 to 66.3 per cent in 1991, but declined to 61.1 per cent in 2002. Between 1991 and 2002, borrowings by cultivator households increased sharply, especially from non-institutional sources. The increase in household indebtedness was largely on account of consumption and similar other expenditures. It is, therefore, possible that the increase in indebtedness of cultivator households to non-institutional sources was also partly on account of consumption expenditures, which could not be easily financed from institutional sources. As a result, the share of non-institutional sources in the indebtedness of cultivator households increased between 1991 and 2002 even as indebtedness of cultivator households to institutional sources grew at a higher rate between 1991-2002 in comparison with 1981-91 (Table 6.4).

Box VI.3

Priority Sector Targets for Scheduled Commercial Banks - Revised Guidelines

The origin of priority sector prescriptions for banks in India can be traced to the Credit Policy for the year 1967-68, wherein it was emphasised that commercial banks should increase their involvement in the financing of priority sectors, viz., agriculture, exports and small-scale industries, as a matter of urgency. However, the concept of the priority sector was formalised in 1972 on the basis of the report submitted by the Informal Study Group on Statistics Relating to Advances to the Priority Sectors constituted by the Reserve Bank in May 1971. On the basis of this report, the Reserve Bank prescribed a modified return for reporting priority sector advances and certain guidelines were issued in this regard in February 1972, indicating the scope of the items to be included under various categories of priority sector. In most of these cases, the guidelines indicated only the general description of the advances to be included and no ceilings were fixed, except in the case of small-scale industry and road and water transport operators where ceilings on the value of original investments were indicated. The scope and extent of priority sector has undergone several changes since then with several new areas and sectors being brought within the purview of this sector.

As per the revised priority sector norms in April 2007, the priority sector definition was rationalised to include only those sectors that impact large sections of the population, the weaker sections and the sectors which are employment-intensive such as agriculture, and tiny and small enterprises. The broad sectors under the revised norms include agriculture (both direct and indirect), small enterprises (direct and indirect), retail trade in essential commodities and consumer cooperatives stores, micro credit, education loans and housing loans.

Under the revised norms, the overall priority sector lending targets at 40 per cent and 32 per cent for the domestic and foreign banks, respectively, as also other sub-targets, have been retained unchanged. However, these are now calculated as a percentage of adjusted net bank credit (ANBC) or credit equivalent amount of off-balance sheet exposures (OBE), whichever is higher, instead of net bank credit (NBC). ANBC includes NBC plus investments made by banks in non-SLR bonds held in HTM category.

Individual farmers, under priority sector advances, can avail of up to Rs.10 lakh against pledge/hypothecation of agricultural produce (including warehouse receipts) for a period not exceeding 12 months, irrespective of whether the farmers were given crop loans for raising the produce or not. Out of the overall 40 per cent target for domestic banks, a sub-target of 18 per cent of adjusted net bank credit or credit equivalent amount of off-balance sheet exposure, whichever is higher, has been set for lending to the agricultural sector. The 18 per cent lending target to agriculture is inclusive of finance provided by banks to farmers indirectly, i.e., through other agencies or indirect finance. However, indirect credit to agriculture should not exceed 4.5 per cent of adjusted net bank credit or 25 per cent of overall credit to agriculture (which is used for computing the performance by the banks under the sub-target of 18 per cent). Under the priority sector norms direct institutional credit to the agriculture sector includes loans sanctioned for small and marginal farmers for purchase of land for agricultural purposes. Distressed farmers indebted to non-institutional lenders can obtain loans against appropriate collateral and group security.

In the revised guidelines, with the aim of overcoming the crowding out effect against small loans, particularly to agriculture, only one-third of amount of the big-ticket loans/ advances are allowed to be classified as direct agriculture. In order to address cases where banks report a ‘nil’ or negligible net bank credit (NBC) on account of its engagement in mostly non-funded business (derivatives), the priority sector lending targets were linked to the credit equivalent of their off balance-sheet business.

In case, the domestic scheduled commercial banks are unable to meet the priority sector lending targets (40 per cent of ANBC or credit equivalent amount of off-balance sheet exposure, whichever is higher) and/or agriculture target (18 per cent of ANBC or credit equivalent amount of off-balance sheet exposure, whichever is higher), they would be allocated amounts for contribution to the Rural Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF) established with NABARD or funds with other financial institutions, as specified by the Reserve Bank. The foreign banks with a shortfall in priority sector lending as per stipulated target/sub-targets are required to contribute to Small Enterprises Development Fund (SEDF), the necessary logistics in this respect have been put in place by Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI).

6.43 As per the statistical returns by banks3, of the direct4 institutional sources of agricultural credit, the share of co-operatives, which constituted the largest share of 57 per cent of outstanding direct institutional

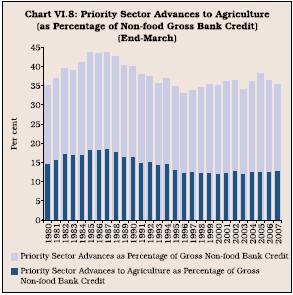

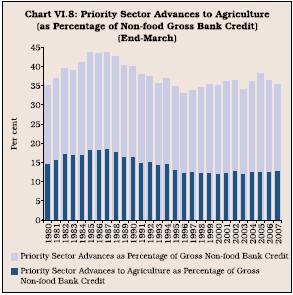

agriculture credit in 1980-81, declined to 32 per cent in 2001-02. On the other hand, the share of scheduled commercial banks (including RRBs), which constituted 43 per cent of outstanding direct institutional credit to agriculture in 1980-81, increased to 68 per cent in 2001-02, thereby emerging as the largest source of direct institutional agricultural credit. However, the share of agricultural credit in the total credit outstanding by scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) showed a sharp decline in the 1990s and at the beginning of the current decade. The share of priority sector advances to the agricultural sector by SCBs in gross non-food credit declined from a peak level of 18.4 per cent at end-March 1987 to 14.8 per cent at end-March 1991 and further to 12.1 per cent at end-March 2001 (Chart VI.8).

6.44 There has been a significant improvement in the share of SCB credit to agriculture in the recent years. The share of agricultural credit in total credit outstanding of SCBs increased from 9.8 per cent at end-March 2002 to 11.8 per cent at end-March 2007, although it was still below the level attained in the early 1990s. The

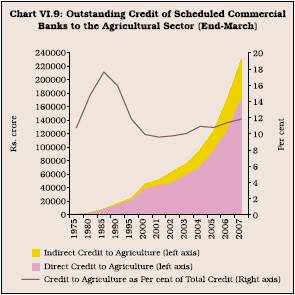

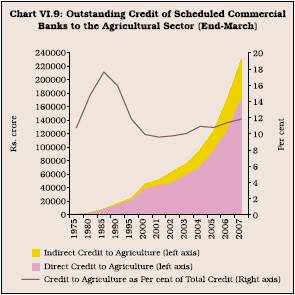

upturn could be attributed to a series of policy measures initiated to improve the credit flow to agriculture. These, among others, included the rescheduling of short-term loans into medium and long-term loans following agricultural distress in several parts of the country, higher credit targets under Special Agricultural Credit Plans for public and private sector banks, and directions to banks to double the flow of credit within three years starting from 2004-05 (RBI, 2007a). As part of the comprehensive credit policy for agriculture announced by the Government of India on June 18, 2004, agricultural credit was to be doubled within three years, with credit to increase at the rate of 30 per cent per year. In terms of financial inclusion, policy efforts were directed towards increasing the coverage of farmers by commercial banks by extending finance at the rate of 100 farmers/branch and financing of 50 lakh new farmers in a year. As a result, growth of SCB credit to agriculture, which was a low 10.6 per cent during the 1990s, accelerated to 26.0 per cent during 2000-01 to 2006-07. Growth of bank credit to agriculture accelerated significantly from 2003-04 onwards, from 23.7 per cent during 2001-02, to 29.2 per cent during 2004-05 and further to 38.8 per cent during 2005-06, before moderating to 33.3 per cent in 2006-07 (refer Table 6.1). A salient feature of the upturn was the sharp increase in the share of indirect finance5 in total credit

by SCBs to the agricultural sector from 16.1 per cent at end-March 2001 to 25.5 per cent at end-March 2007 (Chart VI.9). The growth in indirect finance was possibly a consequence of the broadening of the scope of items covered under the indirect bank finance to the agricultural sector.

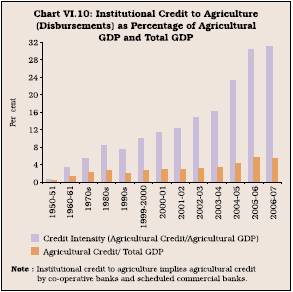

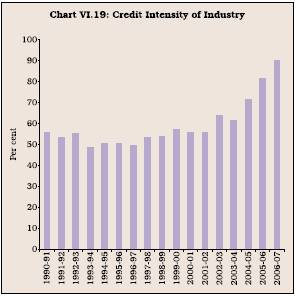

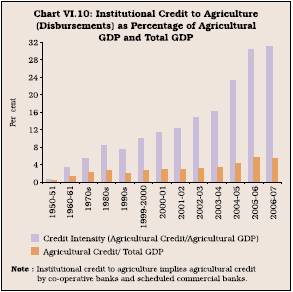

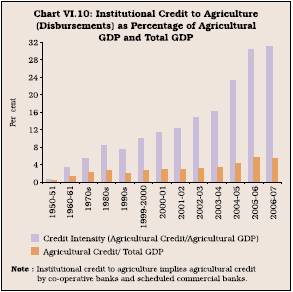

6.45 As a result of the various policy initiatives to improve the flow of credit to agriculture, credit to agriculture from institutional sources as percentage of agricultural GDP (credit intensity) increased sharply from 11.3 per cent in 2000-01 to 31 per cent in 2006-07. The share of agricultural credit from institutional sources in total GDP (at factor cost at current market prices) also rose from 2.8 per cent in 2000-01 to 5.4 per cent in 2006-07 (Chart VI.10). One striking aspect of this increase in credit intensity of the agricultural sector was that it was occurring at a time when the value added by agriculture as a ratio to GDP was witnessing a decline (Mohan, 2006).

Agricultural Credit by SCBs: Bank Group-wise

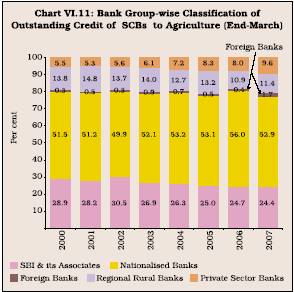

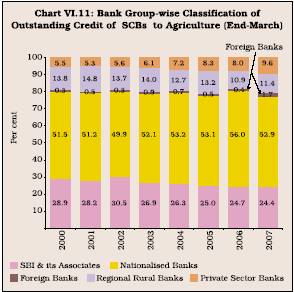

6.46 Bank group-wise distribution of credit of scheduled commercial banks suggests that at end-March 2007, more than half of outstanding bank credit to agriculture was contributed by the nationalised banks group (52.9 per cent) and around one fourth by the State Bank group (24.4 per cent). Among scheduled commercial banks,public sector banks, thus, together accounted for more than three fourths (77.3 per cent) of credit to the agricultural sector. Over the years, while the share of SBI and its associates declined, that of nationalised banks and private sector banks increased. The share of regional rural banks, which were primarily set up to provide timely institutional credit in rural areas specifically to agriculture, declined to 11.4 per cent at end-March 2007 from around 13.8 per cent at end-March 2000. The share of private sector banks witnessed a moderate increase during the period 2000-2007 (Chart VI.11).

Agricultural Credit by SCBs: By Type of Loans

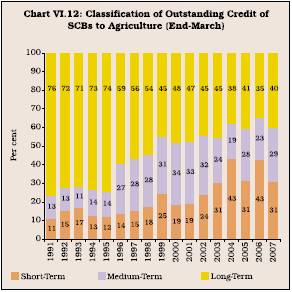

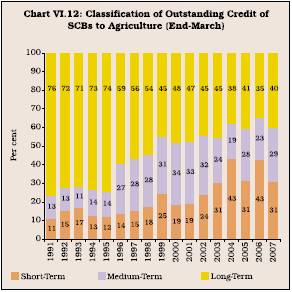

6.47 The trend in credit to agriculture by SCBs based on type of account reveals that the share of long-term loans6 in total outstanding credit to agriculture has declined sharply since the early 1990s. This was in contrast to the pattern in overall bank credit, wherein the share of long-term loans in total bank credit increased sharply. The share of long-term loans to agriculture in outstanding credit by SCBs to agriculture declined sharply from 76.3 per cent at end-March 1991 to 59.3 per cent at end-March 1996, to 40.7 per cent at end-March 2005 and further to 34.7 per cent at end-March 2006 before showing an improvement to 39.8 per cent at end-March 2007.

6.48 On the other hand, the share of short-term credit7 in total agricultural credit by scheduled commercial banks increased significantly from end-March 2002 while that of medium and long-term loans declined (Chart VI.12). This increase in the

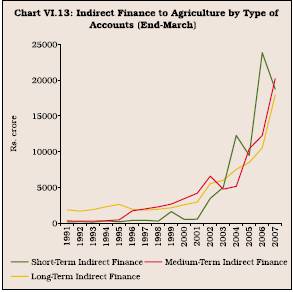

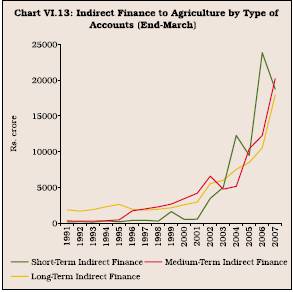

share of short-term credit from 2002 was contributed largely by the sharp increase in short-term indirect finance. Short-term indirect finance to agriculture increased from Rs.165 crore at end-March 1991 to Rs.23,829 crore at end-March 2006 before declining to Rs.18,714 crore at end-March 2007 (Chart V1.13). As a result, the share of short-term indirect credit to agriculture in short-term credit to agriculture increased from 16.2 per cent at end-March 2001 to 58.4 per cent at end-March 2006 before declining to 45.9 per cent at end-March 2007. The decline in the share of term loans could be the result of both supply and demand side constraints. On the demand side, the demand for credit for investment may have been adversely affected due to reduction in the average size of land holdings. Between 1991-92 and 2003, the number of operational holdings increased from around 93 million to around 101 million, whereas the area operated declined from around 125 million hectares to around 108 million hectares, resulting in a decline in average area operated from 1.34 hectares in 1991-92 to 1.06 hectares in 20038. On the supply side, banks might also be interested more in short-term credit as it bears low credit risk, entails lower supervision and monitoring costs, and facilitates a better asset liability management (Golait, 2007).

Agricultural Loans by SCBs: By Size of Land Holdings

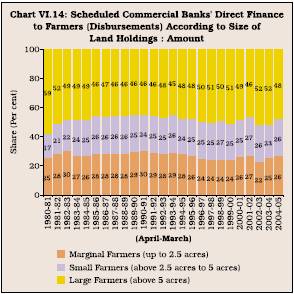

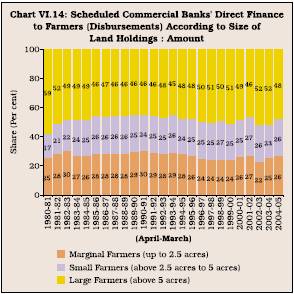

6.49 The underlying objective in granting priority sector status to agriculture was to ensure that credit flowed specifically to the small and marginal farmers, who constituted the bulk of the agricultural labour force. Data on loans disbursed by SCBs to agriculture, according to the size of land holdings, revealed that the share of marginal farmers (with land holdings up to 2.5 acres) in the total agricultural loans remained broadly at the same level between 1980-81 and 2004-05. The share of small farmers (with land holdings above 2.5 acres and up to 5 acres) increased from 16.6 per cent in 1980-81 to 26.2 per cent by 1985-86 and remained broadly at that level thereafter, while that of large farmers (with land holdings of above 5 acres) declined from 58.5 per cent in 1980-81 to 46.2 per cent in 1985-86 and remained broadly at the same level thereafter (Chart VI.14). Thus, even when loans to small and marginal farmers in absolute amount increased by more than ten times between 1990 and 2005, their share in total agricultural loans did not show any significant improvement.

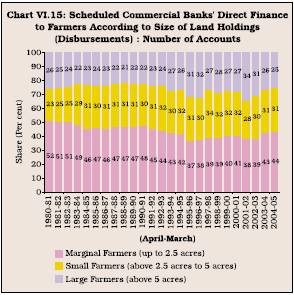

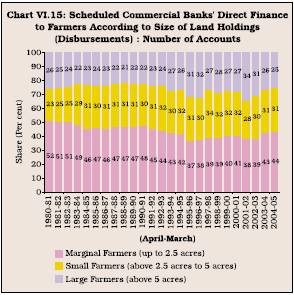

6.50 In terms of number of loan accounts, the share of marginal farmers in total number of agricultural loan accounts declined from 51.7 per cent in 1980-81 to 37.4 per cent in 1995-96, before recovering to 44 per cent in 2004-05 (Chart VI.15).

Agricultural Credit by SCBs: Small Loans to Agriculture

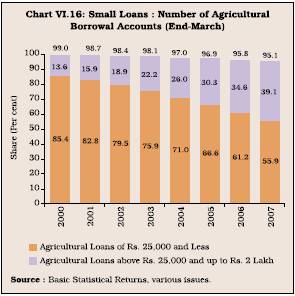

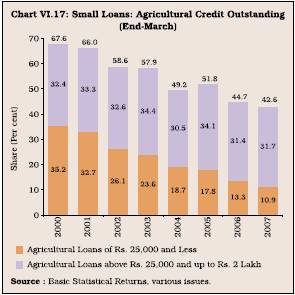

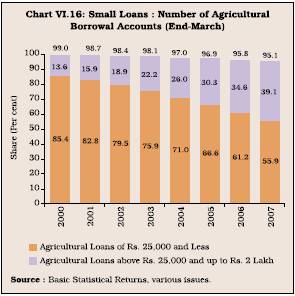

6.51 Small loans to agriculture (comprising borrowal accounts up to Rs.2 lakh as per the revised cut-off limit for small loans effective March 1999), which constituted around 99 per cent of total number of agricultural borrowal accounts at end-March 2000, declined moderately to 95.1 per cent at end-March 2007. The further break-up of small loans category shows that the share of small borrowal accounts with a credit limit of less than Rs.25,000 in total number of agricultural borrowal accounts declined from 85.4 per cent at end-March 2000 to 55.9 per cent at end-March 2007. However, the share of small borrowal accounts with credit limit greater than Rs.25,000 and up to Rs.2 lakh in total number of agricultural accounts increased from 13.6 per cent at end-March 2000 to 39.1 per cent at end-March 2007 (Chart VI.16).

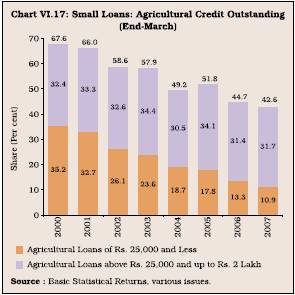

6.52 The share of agricultural credit outstanding to small borrowal accounts up to Rs.2 lakh in total agricultural credit declined from 80.9 per cent at end-March 1992 to 67.6 per cent at end-March 2000 and further to 42.6 per cent at end-March 2007. This was primarily on account of a significant decline in the share of agricultural credit outstanding in respect of small borrowal accounts with a credit limit size class of Rs.25,000 and less (Chart VI.17).

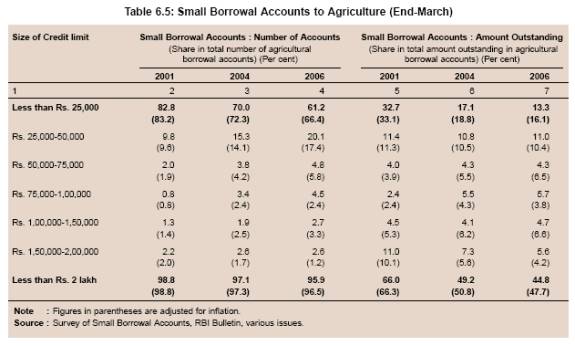

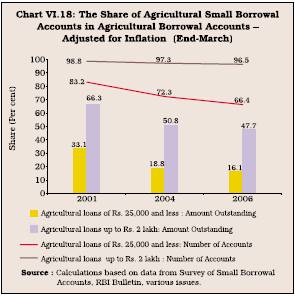

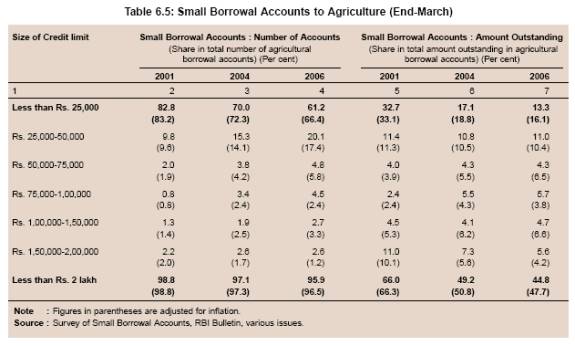

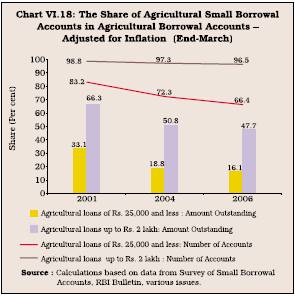

6.53 The decline in the share of agricultural small borrowal accounts (which comprise accounts up to credit limit size of Rs.2 lakh) in terms of number of accounts and amount outstanding was partly due to inflation effects. The credit limit size classes are expressed in nominal terms and over a period of time, on account of inflation, there is a possibility that the value of these credit limit size classes in real terms has fallen. On the basis of the 'Survey of Small Borrowal Accounts', for the period 2001-2006, after adjusting the credit limit size classes under small borrowal accounts for inflation9, the decline in the share of number of agricultural small borrowal accounts in total number of agricultural borrowal accounts persisted, although the extent of decline was somewhat lower. The share of number of small borrowal accounts with a credit limit of Rs.25,000 and less (which is the credit limit size with the most number of agricultural small borrowal accounts), after adjusting for inflation declined. However, the decline was of a lower order when adjusted for effects of inflation. The share of amount outstanding under agricultural small borrowal accounts in total credit outstanding to agriculture, after adjusting for inflation effects, also witnessed a decline, although of a lower order than without adjusting for inflation effects (Table 6.5 and Chart VI.18).

Cross-Countr y Exper iences in Lending to Agriculture

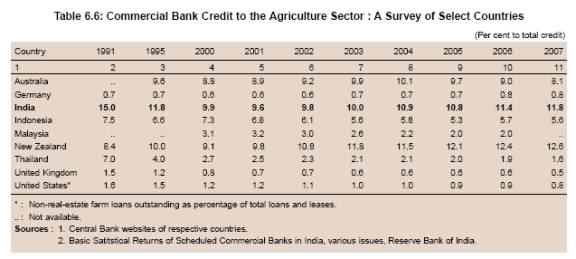

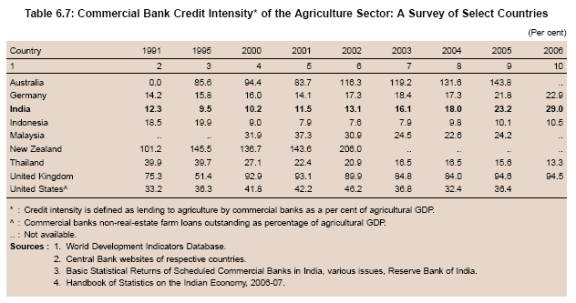

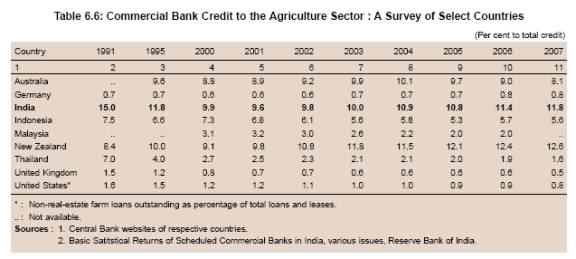

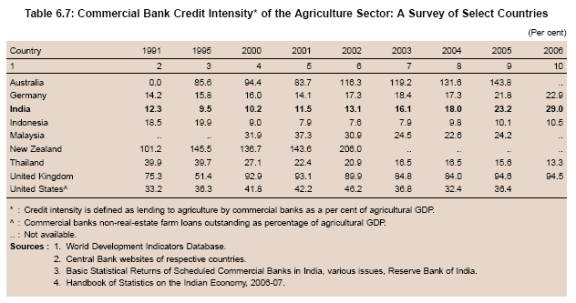

6.54 In 2007, New Zealand was the only country in the sample studied in which the agricultural credit share in total credit of commercial banks was higher than that of India (Table 6.6). Among the countries reviewed commercial bank credit intensity of the agricultural sector in India (i.e., agricultural credit of commercial banks as percentage of agricultural GDP) was similar to that in other East Asian emerging economies. However, credit intensity of agriculture was significantly higher in countries such as New Zealand, Australia, the UK and the US (Table 6.7). This could be mainly due to the higher level of commercialisation of agriculture in these countries, which demands increased credit for technological upgradation, for food processing activities and also for marketing systems for agricultural products.

6.55 To sum up, in India, the share of institutional credit in total agricultural credit has increased significantly since the mid-1960s (Government of India, 2007b). Co-operative banks were the predominant source of institutional agricultural credit in the 1970s and the early 1980s, while scheduled commercial banks emerged as a major source from the mid-1980s. The

share of institutional credit in the indebtedness of cultivator households declined between 1991 and 2002. This was mainly on account of a sharp increase in borrowing from non-institutional sources. Borrowings by cultivator households from institutional sources in the 1990s continued to grow more or less

at the same rate as during the 1980s. However, credit growth to agriculture by SCBs picked up significantly from 2003-04. As a result, the share of credit to agriculture in total credit by SCBs increased in recent years. Priority sector advances to agriculture as percentage of non-food bank credit also increased. As a result, credit intensity of the agricultural sector improved. However, some disquieting features were also observed. One, the share of long-term loans in total credit to agriculture declined almost consistently between 1991 and 2006; the share in 2006 was less than half of the share in 1991. Two, the share of marginal farmers in direct finance to farmers and in total credit accounts held by them showed little perceptible improvement. Three, the share of loans up to Rs.2 lakh, interest rates on which continue to be partially regulated, witnessed a decline both in credit accounts and amount outstanding. However, this decline persists even after adjusting for inflation, although the decline was of a lower order after adjusting for inflation.

Issues in Bank Credit to Agriculture

6.56 Agricultural credit as percentage of total bank credit showed a persistent decline from the early

1990s to 2000-01. This period was also characterised by a decline in the share of agriculture in GDP. Therefore, a more relevant measure to evaluate the agricultural credit performance would be credit intensity, i.e., agricultural credit as percentage of agricultural GDP. Credit intensity of agriculture, which rose continuously between the early 1950s and the 1980s, declined in the 1990s. Growth in bank credit to agriculture, however, accelerated significantly from 2003-04 on account of the various policy initiatives by the Government and the Reserve Bank. As a result,

credit intensity began to increase sharply from 2003-04 onwards. However, insofar as the priority sector credit norms for agriculture are concerned, the credit flow to agriculture has been below the priority sector target of 18 per cent for agriculture since early 1990s. Only eight of the 28 public sector and three of the 26 private sector banks met the target of extending 18 per cent of the net credit outstanding to agriculture at end-March 2007 (RBI, 2007b). The shortfalls in priority sector lending targets by the commercial banks are required to be deposited with the Rural Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF) maintained with NABARD. Thirteen annual tranches of RIDF have so far added up to Rs.72,000 crore (NABARD, 2007). The Union Budget for 2008-09 has budgeted the corpus of fourteenth tranche of RIDF, i.e., RIDF-XIV for 2008-09 at Rs.14,000 crore.

6.57 Although the overall flow of institutional credit has increased in recent years, there are still several issues in agricultural credit delivery arising out of structural transformation taking place in the agricultural sector. First, a change in the pattern of demand for agriculture is emerging as the agricultural sector is getting increasingly diversified and the required scale of finance is increasing. Second, though substantial proportion of Indian agriculture continues to be a ‘small farm’ based economic activity, it is increasingly moving from a system of farmers’ own-resource based subsistence farming to input-based intensive commercial farming. However, at present, the banking system in India is geared more to financing the traditional crops like cereals. It needs to reorient itself to meet the changing requirements of commercialisation of agriculture with heterogeneous production cycles. There is an increased demand for allied activities such as dairy, fishing and livestock, cash crops, besides ancillary activities such as sorting, grading, processing, packaging and transporting to final destinations and markets. Other service sector activities that spin-off the main activities are also growing. On the part of the banks, this would call for designing innovative schemes and products which recognise the differing nature of agri-business and supply chains for different products. More importantly, increased commercialisation of agriculture would call for newer forms of credit assessment and risk-management systems to be put in place, besides upgrading skills and changes in attitudes and mindsets. The banking system may also have to address the problem of “financial dualism”, characterised by faster modernisation of urban financial markets compared with their rural counterparts and the “digital divide”, which separates those using modern computers and communication technologies from those who do not. Financial dualism could result in large farmers, agri-business and rural industries obtaining financial services from modern urban financial institutions, while small and marginal farmers and landless labourers may have to depend on micro-finance and personal savings (Mohan, 2006). More or less similar issues in effective credit delivery to the agriculture sector are confronted by several other developing countries and even advanced countries (Box VI.4).

International Experiences in Credit to the Agricultural Sector

6.58 Broadly, agricultural finance systems in various countries can be classified into three categories, viz., the developmental model, the mixed market model and the market liberal model (Coleman and Grant, 1998). In developmental model, the state plays a proactive and dominant role in agricultural finance activities. This, among others, takes the form of providing long-term credit, where commercial banks are reluctant to participate. For this purpose, specialised corporations are established, interest rates are charged lower and subsidised loans are provided to agriculture. In a mixed market model, there is an orientation towards market-based provision of infrastructure for agriculture, while at the same time a special role for direct state intervention is retained. In such a model, though state supported agencies exist, they cater to the broader agri-food sector rather than agriculture producers and they work in direct competition with the commercial banks. Finally, in a market liberal model, there exists no specific support for agricultural farmers and marginal producers and the credit needs of agriculture, as in the case of other sectors, are met by the banking system. Most of the countries follow one of the three models or a mix of the three. However, the specific lending practices have evolved in accordance with the country-specific needs and characteristics (Box VI.5).

6.59 Most developing countries followed largely ‘supply-side’ oriented directed credit programme till the 1980s. A review of agricultural credit delivery mechanisms in developing countries revealed that results of the supply-led thrust to agricultural credit were disappointing for several reasons. First, for agriculture, more than liquidity the immediate need is that of flexible services, which are generally provided by informal lenders. Second, despite empirical evidence of significant saving potential of small farmers, the agricultural credit markets failed, which could be attributed to inadequate public investment in legal and physical infrastructure, enforcement mechanisms and commodity risk mitigating mechanisms. Third, the fungible nature of money, provided as credit, very often resulted in funds being used for purposes other than investment, thereby reducing the effectiveness of credit in enhancing productivity. There were some examples of successful credit programmes, which were primarily due to strong village co-operative systems and social cohesiveness along with institution building and development of legal and physical infrastructure (Yaron, 1992; FAO, 1998; Meyer and Nagarajan, 2000). However, with non-sustainability of directed credit in many developing countries, ‘demand-centric approach’ – where the stress is more to meet the unique credit requirements of the farmers, especially the small and marginal farmers through specific products – has been adopted, focusing on the viability of banking. Noteworthy among them are the success stories of Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI) and its BRI- UD (Unit Desai) system in Indonesia and Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Co-operatives (BAAC) in Thailand (Box VI.6).

Box VI.4

Issues in Agricultural Credit - Developing Countries’ Perspective

Agriculture plays an essential role in developing economies, especially because the large proportion of the population is engaged in agriculture in developing countries as also for strategic reason of ensuring food security. The variety in farming activities and farm management poses challenges and opportunities to agricultural and rural lenders. It is common that policymakers, particularly in developing countries, have been confronted with the task of resolving a number of issues in agricultural lending.

The basic challenge faced is that providing finance to agriculture and rural development is not seen as a commercial and business opportunity by the banks or for that matter by the formal financial systems. Unlike in the past, the present day agriculture has become increasingly capital intensive which requires access to working capital and seasonal loans along with medium and long-term credit for on-farm investments and cannot modernise without the suppor t of a strong financial system. Significantly, even small farmers generally have no access to formal credit because the financial system is not innovative or sufficiently efficient to reduce transaction costs and to provide ‘tailor-made’ products to small clients at affordable cost.

Two major factors that hamper the smooth flow of credit to agriculture are the absence of effective credit delivery systems and the lack of adequate credit absorptive capacity of the rural populace.

In agricultural lending, the cost for delivery and monitoring of credit is found to be very high and the banks have not yet found an easy solution to manage the cost of credit delivery and supervision in the agricultural sector within the discipline of balance sheet numbers. Distances between clients and financial intermediaries, transport and communication difficulties, and the risky nature of agriculture that is vulnerable to natural disasters, boost these costs. The challenge still is to design and deliver the provision of loan products to better suit the farming community. Weak land titling and cumbersome and costly court procedures also compound the problems of providing conventional collateral for loans in rural areas, thereby further increasing the risks of rural lending. Another major issue confronting the agricultural and rural credit is that standard credit programmes are not suited to the heterogeneous needs of small farmers. Subsidised interest rates blocked the emergence of vigorous and competitive rural financial markets, fostered loan repayment indiscipline, prevented banks from covering costs, and discouraged local savings mobilisation. Complexity of various outdated procedures and the related paper-work involved in provision of credit is another issue in agricultural lending.

Rural financial markets cannot thrive and grow if their clients lack creditworthiness. The low absorption capacity of farmers, inability to repay loans, and the inability to save because their incomes are depressed, all result in low creditworthiness. Notwithstanding improvements in the information technology, banks lack essential information on the credit history of potential clients, the viability of on-farm investments, the self-financing capacity of farmers and their repayment capability. Lack of these vital pieces of information hampers the timely credit reach for agriculture and rural development.

As most of the farmers are either small or marginal in the developing countries, they lack the absorptive capacity both in terms of cost and the size of loans and advances which are of cost effective size to be handled by the banks. Since many of the financial transactions in rural areas are small -both for loans and for deposits - the transaction cost per unit of money involved is necessarily high compared to larger transactions. Most of the banks either lack risk management system or they feel it is not necessary to have one, especially when it comes to financing agriculture.

References:

Klien Brigette, Meyer Richard, Hanning Alfred, Burnett Jill and Ficbig Michael. 1999. “Better Practices in Agriculture Lending.” Agricultural Finance Revisited No.3, FAO, December.

RBI. 2004. “Report of the Advisory Committee on Flow of Credit to Agriculture and Related Activities from the Banking System.” June.

6.60 To sum up, institutional credit to agriculture has made considerable progress since the mid-1960s. The share of institutional agricultural credit in total credit to agriculture increased from 18.7 per cent in 1961 to 66.3 per cent in 1991. In particular,

Box VI.5

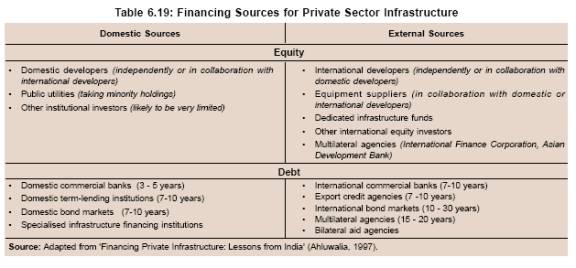

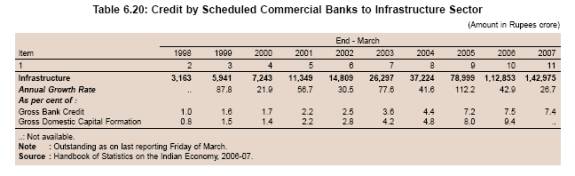

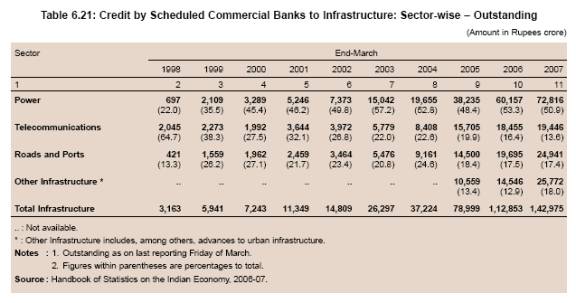

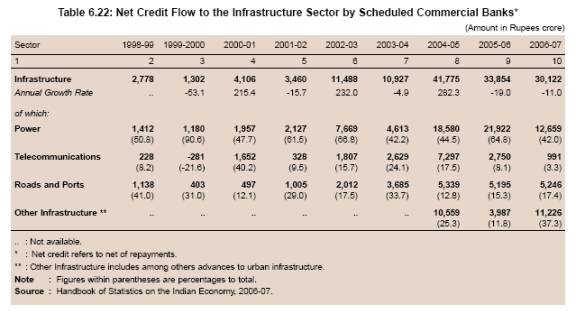

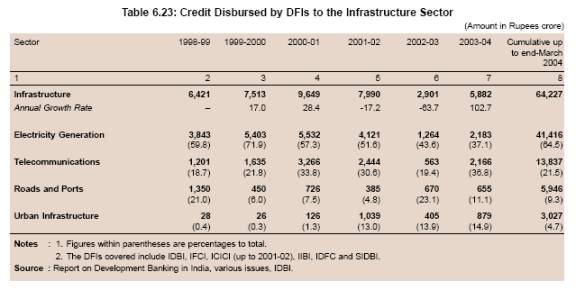

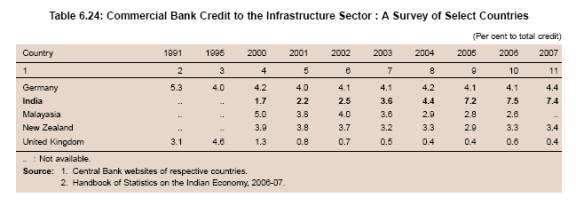

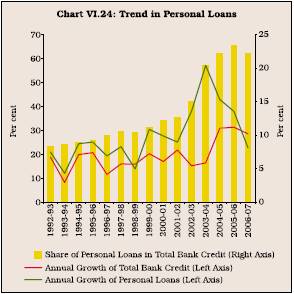

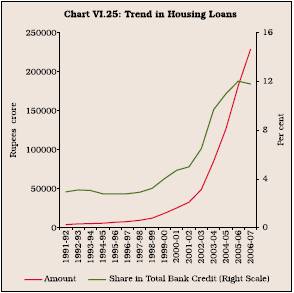

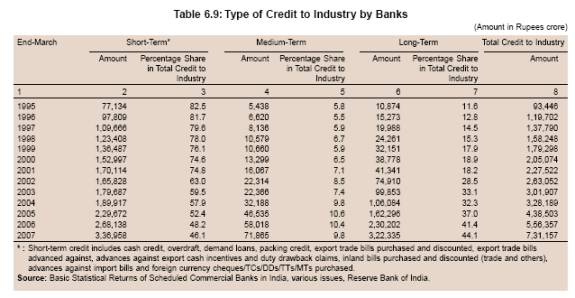

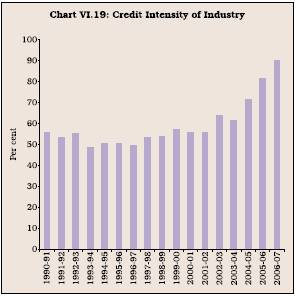

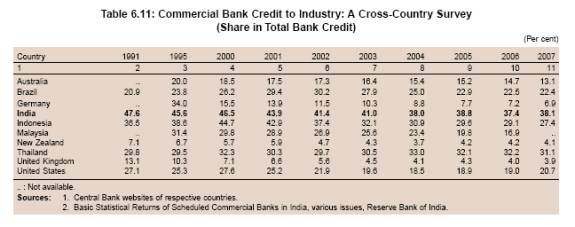

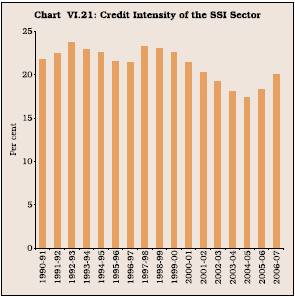

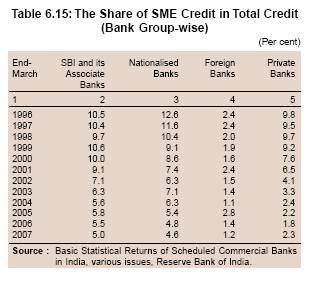

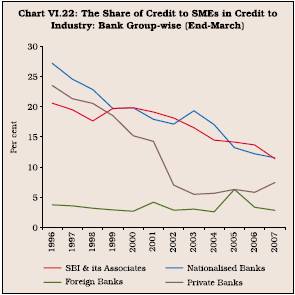

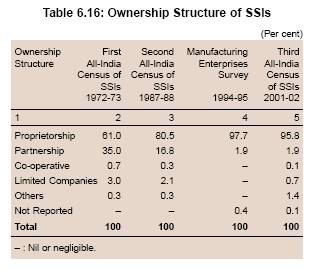

Agricultural Lending Practices: Cross-Country Experiences