IST,

IST,

Risks Associated with Macroeconomic Adjustments: Global Perspective

Dr. Rakesh Mohan, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India

delivered-on అక్టో 13, 2006

I. Growth Trends I am happy to observe the continued healthy expansion of world GDP and that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is projecting only a marginal slowdown from 5.1 per cent in 2006 to 4.9 per cent in 2007. It is important to note, however, that some other forecasters are not so sanguine. The global economy has maintained its pace of growth in the first half of 2006. Although growth rates recorded in most of the advanced as well as emerging economies have exceeded their earlier projections, the US does appear to be slowing down in the face of headwinds from a cooling housing market. Expansion has continued in the euro area, which along with a sustained recovery in the Japanese economy bodes well for world growth prospects. China and India have continued to grow at an accelerated pace and the rest of Asia has also maintained its growth momentum. China and India certainly will continue to exhibit healthy growth next year. The IMF projects that China is expected to grow at 10 per cent in 2006 as well as in 2007, while the growth projection for India has been placed at 8.3 per cent for 2006 and 7.3 per cent in 20071 (Table 1). Considering these developments, the projections by the IMF for the world economy at 5.1 per cent in 2006 and 4.9 per cent in 2007 may not be over optimistic, barring a really severe US slowdown. During 2007, a slowdown, which is expected in most advanced economies, will be partly * Presentation by Dr. Rakesh Mohan, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India in the Meeting of G20 Finance and Central Bank Deputies held in Sydney, Australia during October 13-15, 2006. Assistance of Rajiv Ranjan in preparing this address is gratefully acknowledged. 1 We may note that official Indian GDP growth estimates have been revised to 9.0 per cent for 2005-06 and the Reserve Bank has projected growth to be in the range of 8.5 – 9.0 per cent for 2006-07. offset by continued strong growth in major emerging markets, particularly in Asia. However, it would depend on how far growth in emerging economies is autonomous of the US growth prospects. Softer demand in economies such as the U.S., Japan and Germany will drive the slowdown as the tightening of economic policy begins to materialise, though indications from Japan and Germany suggest a continuing recovery. However, emerging Asia is still considered to be the fastest growing region of the world, which would prop up the global economy in 2007. So far high oil prices have had a limited impact on economic growth as demand rather than supply has been the major driver of price rises. International oil prices have, however, eased in recent months possibly on account of a series of positive supply side developments before picking up again more recently. If further sustained increase in prices prevails2 , it may aggravate the growth

2 The mild winter in the US and Europe 2006-07 has subsequently contributed to the cooling of oil prices for the present. concerns for 2007 as the consequences could be much worse this time round. In the face of heightened uncertainties with regard to slowdown in growth in advanced economies like the US, coupled with inflation concerns, policy makers are finding it increasingly difficult to gauge appropriate policy responses for supporting growth while fighting off renewed bouts of rising inflation at the same time. II. Risks to the Global Economy As a central banker, I have to admit that nothing worries us more than collective impression of no risks on the horizon. As Mr. Mervyn King is reported to have said, when asked what do central bank Governors do in their bi-monthly meetings in Basel: “we get together to worry together”. Accordingly, I was also disturbed in the last IMF Article IV Mission to India that found little to worry about! Then, what are the worries at the present juncture? As almost all commentators would list, let me reiterate the common concerns. 1. Continuing Uncertainties Related to Oil Prices The issue of rising oil prices has been a source of concern for policy makers for some years. The reasons of rising oil prices are of course multiple including limited spare capacity, geo-political uncertainties, and the like. In contrast, others believe that the price of oil is almost entirely speculative, and that the increase in price is due to oil speculation extending into the long term. They argue that speculators foresee increasing demand, decreasing supply, or both, leading to a long term increase in the price of oil. Uncertainties with regard to rising oil prices leave the countries particularly the biggest consumer like US and China highly vulnerable to any supply disruption and/or ratcheting up of prices. During the first eight months of 2006, the average petroleum spot prices has surged by 16 per cent. It appears that price increases since 2003 have had some dampening effect on demand but continued buoyancy in most of the major countries, especially China and US has prevented a fall in overall consumption (IMF, 2006). Since the issue of elevated international oil prices has been discussed and analysed a lot over the time, I would like to conclude by highlighting four points, two negative and two positive. (a) The overall demand supply situation remains tight and is expected to remain so over the next few years. Hence, a high level of international oil prices may continue and any small disturbances will lead to high volatility and uncertainty. (b) If there is a world GDP slow down, it could affect developing country oil importers very adversely. (c) There seems to be further scope of improving the oil use efficiency by enhancing productivity, and the US can go a long way in improving the oil economy. (d) Use of oil resources by the oil exporters, if put in real investment, could stimulate the world economy. 2. Possibility of Inflationary Pressures The global economy proved remarkably resilient to the sharp rise in energy and metal prices till early 2006. This is perhaps partly attributable to the fact that overall pass through has not yet materialised across many countries to greater globalisation and competition in product markets, increase in energy efficiency, lower oil-GDP ratio and lower raw material intensity in production process (lower share in value added). However, in recent months, headline inflation in many of the major advanced economies and emerging economies has been above central bank comfort zones3 on account of rising oil prices but there are now signs of increases in core inflation as well. Major central banks have reacted to upside risks to inflation (Table 2). Energy prices and more recently certain non-oil commodities like metals have been a major source of build up of inflation pressures in most of the economies. During the first eight months of 2006, in the US, the consumer price index (CPI-U) rose at a 4.6 per cent seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR). This compares with an increase of 3.4 per cent for all of 2005. The index for energy, which rose 17.1 per cent in 2005, advanced at a 22.3 per cent SAAR in the first eight months of 2006. Despite the fact that the world economy has coped remarkably well with sharp rises in energy and metal prices the following four factors indicate a worrisome picture: (i) The overall monetary overhang of prolonged monetary accommodation in the US/Europe/Japan should, in principle, bare its ugly inflationary effects at some point. 3 As oil prices have fallen from their $70+ peaks, headline inflation has also tended to moderate in developed countries.

(ii)

The sustained high oil and metals price would also be expected to pass through

gradually. (iv) Increasing food prices, particularly in developing countries is another concern in the global context. In short, there are risks that continued high inflation may seep in to high inflation expectations and higher wage demands leading to cost push pressures in the US. Further supply concerns in the oil market may aggravate such inflation concerns and as mentioned earlier posing the challenge of growth-trade off for the central banks. The emerging scenario with regard to inflationary concerns would depend on how equipped we are as monetary authorities and fiscal authorities to manage these incipient risks. It would hinge upon (i) how far can monetary tightening go without impacting GDP growth, and (ii) how far rising interest rates could impact new investment. 3. Cooling of Housing Markets in the US The US housing market has already shown signs of cooling down and the US Chair can perhaps inform us more on this issue. Any abrupt cooling of housing market in US is likely to weigh down US consumption and thus its growth prospects, which in turn, would have adverse spillover effects on major trading partners like China and other emerging economies. The US economy is decelerating moderately and this trend is expected to roll over well into 2007 as growth is likely to moderate at 2.9 per cent, driven primarily by an expected sharp slowdown in household expenditure and more modest business investment. By some measures, prices of existing homes have leveled off in nominal terms, house sales have fallen, and inventory/sales ratios have risen sharply. Residential investment has already subtracted about 0.5 percentage point from second quarter US GDP growth, more than many observers expected. How much this slowdown will affect consumption is unclear. According to Ben Bernanke, the Fed Chairman, “the decline in US residential construction would subtract “about one percentage point” from growth in the second half of this year and “probably something going into next year as well”. The ultimate determining factors in this context would be (i) how far the housing market correction will last, (ii) what would be the magnitude of its impact on the rest of the sectors, and (iii) how other sectors like equity, non-resident construction sectors behave in the period ahead. Importantly, a “substantial correction” in the US housing market is going on but so far it has not had a big effect on the rest of the economy and has yet to translate into significantly lower consumption. To date there is little evidence that this correction in the housing market has had any significant adverse spillover effects on other parts of the economy. The production of construction supplies has decelerated, but in general, surplus resources available in the residential market appear to have been largely absorbed in nonresidential building or elsewhere. The cooling of housing market may erode household expenditure by dampening the wealth effect but trends in equity market, growth in wages and oil prices would also be important determinants of US consumer spending. Therefore, the ultimate outcome would hinge upon the confluence of these factors. It may be noted that both the housing and equity boom have been important drivers of growth in recent years. Furthermore, there has been substantial off-setting strength in other sectors, including non-residential construction and we may witness a soft landing. 4. Abrupt Adjustment to Global Imbalances The build-up of global macroeconomic imbalances poses a serious threat for the global economy as the US current account deficit continues to widen as does the Chinese surplus (Table 3). In the US, the current account deficit widened to 6.4 per cent of GDP in 2005 and 6.6 per cent in the second quarter of 2006. The budget and current account deficits need to be seen in a more holistic perspective as fiscal shortfalls, especially with the economy nearing full employment, intensify the need for foreign capital. The greatest threat to the US fiscal position over the long-term comes from unsustainable growth in entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare. The US Budget for FY 2007 carried some proposals for savings and reforms to mandatory spending programs. How far these measures would contribute towards halving of the budget deficit by 2008 and thus leading to narrowing of US current account deficit is yet to be seen. The important question in this regard is – do we need coordinated structural action or will the market mechanism work? Although alternative scenarios are widely discussed yet it is difficult to be decisive with regard to the final solution. While the correction can be envisaged through joint policy action across different regions for moving towards a more orderly adjustment but consensus on such correcting policies

across policy makers may be an issue. In this regard, the IMF is conducting its first multilateral consultations, involving the U.S., the Euro area, Japan, China and Saudi Arabia to assess how joint efforts by key countries can contribute to reducing global imbalances while maintaining healthy growth. In an alternative scenario, adjustment could be automatic through the market mechanism but the crucial issue is whether it will be in an orderly fashion or otherwise. It is, however, clear that emerging Asian economies along with the oil exporting countries would have a greater stake in the adjustment process. The concern, therefore, warrants a better understanding of policy issues so that appropriate and timely policy actions can be taken in such a manner that adjustments can take place in an orderly fashion. I have expressed my apprehensions regarding the efficacy of the exchange rate adjustment mechanism in various fora. There seems to be some moderation in exchange rate pass through due to the lower share of manufacturing in GDP and the globalisation of production. Hence the effect of exchange rate adjustments on consumption and other behaviour appears to be muted. Policy actions which can work toward an orderly adjustment could be:

5. Risk of GDP Slowdown Sustained growth in the global economy in recent years has absorbed spare capacity and led to some emerging signs of inflationary pressures. Output gaps seem to be closing in the advanced countries and narrowing in emerging market economies. Such a scenario makes the potential growth prospects of the world economy more uncertain with the underlying risk of growing inflationary pressures in the years ahead. This suggests that there is need for new investment to create further capacity or that aggregate demand would have to be managed within the present limits of productive capacity. Business sentiment, which seems to have picked up globally, may bode well for a further strengthening of corporate investment. However, given the present scenario marked with uncertainties with regard to growth and also the global economy operating near the potential level of output, policy makers are likely to face challenges of an optimum policy mix of monetary and fiscal policy. Central banks of major economies like the US are facing the paradox of an expected slowdown along with the possibility of incipient high inflationary pressures. While on one hand, inflationary pressures force central banks to have a tightened monetary policy stance, the expectation of a slowdown in major economies warrant an expansionary monetary policy. The question now is whether fiscal policy can provide any cushion. Since these countries are also facing fiscal strain in the form of high current account deficits and fiscal deficits, there may not be any further headroom for expansionary fiscal policy. Therefore, in the short to medium run one cannot expect much expansion in the global production capacity out of public expenditure at least. Given the limited existing spare capacity and fiscal challenges for most of the countries, policy makers will have to manage aggregate demand through an optimal policy mix so as to maintain a balance between growth and price stability which of course would depend on country-specific circumstances. 6. Growing Protectionism A major offshoot of the global slowdown and disorderly adjustment to global imbalances could be the intensification of a protectionist wave across the major advanced countries. The OECD has estimated the gains at nearly US$ 100 billion in terms of increased economic activity and hence prosperity –that could be obtained from full tariff liberalisation for industrial and agricultural goods. The benefits from liberalising trade in services – the fastest growing sector of the world economy - could be five times higher, at around US$ 500 billion. Thus, these ongoing developments, not entirely mutually exclusive, pose some threat to the growth prospects in the advanced economies. 7. Food Prices Rising food prices are another emerging challenge for the global economy in general, and developing economies in particular. The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) projects an increase of over 2 per cent in the world food import bill in 2006 compared to 2005. Given the higher share of imports of food and feed, developing countries’ import bill is expected to grow by 3.5 per cent, while that of low-income food-deficit countries is forecast to increase by nearly 7 per cent (FAO, 2006). The food price index rose 11 per cent between January–July 2006 (IMF, 2006). Unfavorable weather conditions early this year reduced grain production significantly, while demand continued at record highs, drawing down already low global stocks. Countries like Australia are facing drought conditions while the agriculture sector in India has remained stagnant. It is difficult to ascertain whether rising food price cycle is a temporary phenomenon? If such a trend in food prices continues, it poses threats not only in the form of further inflation, but would also have serious equity implications internationally. To the extent that food has a larger weight in the consumption basket in developing countries, similar sectoral price increases would result in higher measured inflation in developing countries. Attributing the rising food grain prices partly to crop based fuel production, Lester Brown of the Earth Policy Institute warns that for the 2 billion poorest people in the world, many of whom spend half or more of their income on food, rising grain prices can quickly become life threatening. The broader risk is that rising food prices could spread poverty and overall instability in low-income countries that import foodgrain. This instability could in turn disrupt global economic progress (Brown, 2006). Furthermore, it is unclear how long the current upswing in world prices will persist? In short, global risks can be enumerated both in terms of demand side as well as supply side concerns. Whether it is negative demand shocks triggered by the sharper slowdown in US housing market or supply side shock in terms of fall in productivity and productive capacity in advanced countries leading to inflationary concerns, it has become a formidable challenge for central banks to decide on lead and lags of their policy actions. These uncertainties not only warrant better coordination between national government and central banks within a country but across the countries. III. Global Macroeconomic Prospects and India In recent years, India’s stake in the global economy has increased as its share in world GDP has increased from 4.3 per cent in 1990 to about 6.2 per cent in 2005. The Indian economy has been growing at an average annual growth rate of nearly 6 per cent since the 1980s, and at over 8 per cent during the last three years, which is likely to be exceeded this year. A Draft Approach Paper to the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-08 to 2011-12) suggests that the economy can grow between 8 and 9 per cent per year (Government of India, 2006)4. India has also shown considerable resilience during the recent years and avoided adverse contagion impact of several shocks. As regards the price situation, it may be noted that pre-emptive monetary actions by the Reserve Bank in the form of hike in policy rates in recent period helped in stabilising inflation expectations 4 The approach paper released in November 2006 has indicated an average growth rate of 9 per cent over the Eleventh Five Year Plan period. in the face of rising international oil prices and domestic demand. Inflation movements in 2006-07 have been driven largely by primary food articles prices. The impact of mineral oils, which have been the major driver of inflation over the past two years, petered out by early September 2006 on the back of base effects. Headline inflation remained within the indicative trajectory although underlying inflationary pressures continued5 . As far as India’s growth prospects in the face of global slowdown are

concerned, it is important to note that the Indian economy is largely domestic

demand driven and is likely to remain resilient on account of its inherent strengths

even if a growth slowdown occurs in rest of the world. We are in fact in the world

of a positive sum game mainly because of increasing trend in saving and investment.

Increase in the domestic saving rate is contributed by a significant turn around

in public sector saving and the sustained high profitability of the corporate

sector. Assuming the trend continues in the coming years, one can imagine that

the Indian economy may achieve higher growth in GDP and per capita GDP. Given

the reform initiatives envisaged under the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management

(FRBM) Act, we expect the public savings to improve further. 5 Inflation has since exceeded the indicative range of 5 to 5.5 per cent and the RBI has taken further measures to withdraw monetary accommodation, along with prudential measures to restructure credit growth in certain sectors. showing robust growth (e.g., business and financial services, retail and construction) for the last few years, need lower capital intensity than the manufacturing sector. This preserves the current pattern of growth and therefore, India may not need or achieve the kind of investment rate that the East Asian countries needed to finance their rapid growth driven by manufacturing sector. It is not merely the difference between the rates of saving but it is the composition of saving that seems to be more striking. In all the East Asian countries as well as in the US, the corporate saving exceeds household saving by a magnitude of 10 per cent (Korea) to nearly 400 per cent in case of Philippines, while for India the reverse is the case. As far as impact of global growth slowdown on the Indian external sector is concerned, it is important to note that not only Indian growth process is more domestically driven but our export basket composition is quite diversified. Our trade deficit on goods accounts is partly financed by the surplus on invisible account particularly remittances and software. However, one unstated worry is that if the trade deficit gets widened in the medium term in the range of 6 to 7 per cent, it may lead to concerns relating to domestic employment prospects. In the event of a global slowdown and a sharper fall in US growth, there may be some adverse impact on software exports and remittances flows to India (Table 4). However, over a period of one and a half decades, the share of the top 10 trading partners in India’s total trade has decreased from 65 per cent in 1990-91 to 46.2 per cent in 2005-06 indicating growing trade

relations and wider diversification across countries. In this context, it may however, be noted that, till recently, the US had a much higher weight in India’s global trade, which is now being supplemented by China and the East-Asian economies (Table 5).

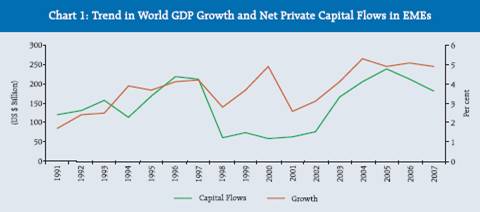

Indian trade has grown faster with these countries than its overall trade growth. Emerging Asian economies accounted for a significant share of around 25 per cent in India’s total exports in 2005-06 (16.0 per cent in 1999-2000) and 23.0 per cent of total India’s imports (16.2 per cent in 1999-2000). China has emerged the second major export destination for India after the US. It has now become the largest source of imports for India, surpassing the US. A similar trend was noticeable vis-à-vis the ASEAN-5 (Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines) but way ahead there is vast scope for expanded trade with these countries. In view of this diversified destination and source of India’s foreign trade, it is unlikely that global slowdown would have any significant impact of trade. Moreover, the export basket of India has become increasingly diversified with certain sectors such as automobiles, pharmaceuticals, textiles, etc., and emerging as driving factor. For example, steel production in India is now among the lowest cost in the world. Pharmaceutical and biotech firms are likewise very competitive internationally. It is important to realise that the traditional face of Indian business has changed dramatically in the last few years. Indian firms are no longer only seekers of foreign technology or producer of staple goods or providers of low-end services. Indian corporate sector have recorded better bottom-line growth with higher sales in recent quarters. Their engagement with the world has acquired new dimensions. Indian firms are increasingly carrying out their own R&D. India has an impressive record when it comes to investment abroad and acquiring brands by its companies. Indian firms are acquiring manufacturing firms abroad to leverage comparative advantage of foreign locations, using synergies between the parent company and the company under acquisition and having production facilities near the major markets. Our patent law is compatible with the best countries in the world. The Indian capital market have been exhibiting buoyancy as resources raised by the Indian corporates through public offerings, private placements and euro issues increased significant. The secondary market registered sharp gains during 2005-06 and continued to surge during the early part of 2006-07 with the benchmark indices recording all time high levels. This trend has continued in the current financial year as domestic stock markets recorded gains during the July-September period offsetting almost all the losses suffered in the meltdown in May-June. Large investments by foreign institutional investors (FIIs) and domestic mutual funds on the back of robust macroeconomic fundamentals, congenial investment climate and strong corporate profitability buoyed the stock markets. In the context of impact of slowdown in the US economy which may have adverse impact on the global economy, it may also happen that in search of low cost, outsourcing from the US and other parts of the globe to India may get boost and compensate any adverse effect which may be in terms of slowdown in software exports or remittances. As in recent years, we have witnessed the coming of age of the Indian IT multinationals, with the traditionally India-centric, indigenous players beginning to build noticeable presence in other locations - through cross-border acquisitions, onshore contract wins and organic growth in other low-cost locations. This has been complemented by global majors continuing to significantly improve their offshore delivery capabilities - predominantly in India, vindicating the success of the global delivery model and highlighting India’s increasingly important role in the new world IT order. With Indian firms exporting services ranging from call centers to medical diagnostics to tutoring, India’s position of strength in information technology is well known. India‘s Information Technology Enabled Services/Business Process Outsourcing (ITES-BPO) industry has demonstrated its sustained cost advantage and fundamental competitiveness. Around 30 per cent annual growth in India’s IT and ITES exports since the mid-1990s reflects the maturity of the Indian service capabilities in meeting the needs of a global customer base and the importance accorded to India as a global sourcing destination. According to NASSCOM (2006), IT software and services exports were US$ 23.4 billion in 2005-06. The large investments of the Government in establishing high quality institutions like the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) and other publicly funded engineering and technical institutions form the human resource backbone of India’s IT and ITES revolution. There had been apprehension in several quarters that with the turn in the interest rate cycle after reaching the minimum of 1 per cent, would lead to slowdown in capital flows towards emerging market economies. Moreover, a moderate degree of correlation has been observed in global growth and net private capital flows in emerging market economies in recent years (Chart 1). Any slowdown may have a concomitant impact on the capital flows to emerging economies. However, the events in the last 2-3 years have shown that India has emerged as a major destination of foreign investment, especially portfolio investments even in this tightening cycle. Furthermore, the trend in foreign capital flows in India would also depend on the trend in interest rate differential between India vis-à-vis other countries mainly source countries. It may happen that with the decrease in Fed rate as is expected in US, emerging markets like India may continue to attract private investors from abroad.

The World Investment Report 2005 has ranked India as the second most attractive investment destination among transnational corporations (UNCTAD, 2005). This is also evident from a recently released survey by ATKearney which, in terms of FDI Confidence Index, has placed India at the second place after China. Their Survey based on opinions of CEOs and CFOs of the world‘s largest 1000 firms finds that investors‘ enthusiasm for investment in China and India is an all time high and India seems to be on the cusp of FDI take off (ATKearney, 2005). Although foreign investment in India has gone up in the past two decades, it has remained well below the foreign investment in countries like China. India ranks as one of the three largest emerging markets in terms of economic size and stock-market capitalisation. Foreigners have invested in more than 1,000 Indian companies which is a record for any country outside the US. Likewise, India is more attractive than ever to global retailers and has topped the 2006 global retail development index of ATKearney as buoyant and sustained growth is likely to support retail industry estimated at US$ 325 billion and expected to grow by 13 per cent in the current year (ATKearney, 2006). A recent study by Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), released in March 2006 projects that emerging markets, China and India in particular, will take a greater slice of the world economy. It also projects that propelled by fast growth in China and India, Asia will increase its slice of world GDP from 35 per cent in 2005 to 43 per cent in 2020. Thus, given the inherent strength of the Indian economy and the interest that we see among the global investors combined with the fact that emerging Asia could continue to drive the global economy, we do not see any major change in the attitude of foreign investors in the wake of slowdown in the global economy. Another advantage we see would help us to withstand any global slowdown is the demographic profile of India which bodes well for prospects of growth. India has the world’s youngest and fastest growing working-age population. India is entering the second stage of the demographic cycle and over the next half-century, a significant increase in both savings rate and share of working age population is expected. In 2020, the average Indian will be only 29 years old, compared with 37 in China and the US, 45 in West Europe and 48 in Japan (Chandrasekhar and Ghosh, 2006). Given our emphasis on human resource development in terms of producing a large number of engineers, technologists, doctors etc., it is expected that a large and young population of India would have high labour productivity along with lower need for social security and health related expenditures, which in turn, could power the growth process of not only India, but would increasingly meet the growing need of other industrialised countries. India, being one of the youngest countries in the world could use its large and growing labour to its advantage in terms of better growth by making efforts towards human capital formation. Given the ongoing buoyancy in the Indian economy and the related need to increase improve infrastructure, there are ample opportunities for both local and international investors. The financial sector in India has witnessed advancements in terms of stability, health and depth. The strength of India’s financial sector could help us to withstand any stress in the balance sheet of the banks due to global slowdown. India has a mature banking and financial system with a network of 84 scheduled commercial banks, 102 Regional Rural Banks and over 68,000 bank branches. India has also made significant progress in financial liberalisation since the institution of financial sector reforms in 1992 and this has been recognised internationally. India has also made significant progress in financial liberalisation since the institution of financial sector reforms in 1992 and this has been recognised internationally. Among emerging economies, India appears to be the most financially solvent. IV. Concluding Observations Growth performance of the world economy has remained satisfactory so far under the relatively benign world environment and concerns with regard to inflation have been well managed by the central banks with calibrated policy responses. However, risks with regard to inflation continue to pose a challenge to monetary and macroeconomic management. In this context, supply side trends in oil, metals and food would be particularly important for the global price situation. It is still unclear how far the upward trend in food prices, which is relatively recent, would continue. At the same time, there are also concerns regarding the rising inflation pressures as the expansion matures in the face of narrowing output gaps across the major growth driving economies, may lead to a cyclical global slowdown as central banks may have to resort to further monetary tightening to contain inflationary pressures. Furthermore, it is yet to be tested how far growth in Europe and Asia is really self-sustained. Although domestic demand in the euro area, and especially corporate spending, strengthened progressively in the first half of 2006 and the recovery also seems to have reached the labour market, private consumption growth might still be fragile; especially the impact on consumer spending of the planned fiscal tightening in Germany and Italy in 2007 remains uncertain. Another risk to be accounted for is the sharp expansion in China, largely based on excessive fixed investment not subject to market discipline, represents a major challenge. Similarly, as rightly mentioned in the IMF background paper, a global slowdown would aggravate the challenges faced by fiscal policy to ensure sustainable fiscal position particularly in the US and some of the European countries. All these risks reinforcing each other have imparted considerable uncertainty to the global growth prospects and also have made decision making for the policy makers a challenging task. References: ATKearney (2005), FDI Confidence Index, Global Business Policy Council 2005, Volume 8, A.T.Kearney, Inc. USA. ATKearney (2006), Emerging Market Priorities for Global Retailers, The 2006 Global Retail Development Index, A.T.Kearney, Inc. USA. Brown, L.R. (2006), “Supermarkets and Service Stations Now Competing for Grain”, Earth Policy Institute, July 2006. Chandrasekhar, C.P and Ghosh, Jayati (2006), “India’s potential `demographic dividend”, Macroscan, Business Line, January 6, 2006. Economic Intelligence Unit, Foresight 2020, Economic, Industry and Corporate Trends, Study sponsored by CISCO Systems, The Economist, March 2006. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, Food Outlook, June 2006. Government of India (2006), “Towards Faster and More Inclusive Growth: An Approach Paper to the 11th Five Year Plan”, Draft Paper by Planning Commission, June 14, 2006. International Monetary Fund (2006), World Economic Outlook, September 2006. NASSCOM (2006), Indian IT Industry: Fact Sheet. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2005), The World Investment Report, 2005: Transnational Corporations and the Internationalisation of R&D, United Nations: New York and Geneva, 2005. * Presentation by Dr. Rakesh Mohan, Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India in the Meeting of G20 Finance and Central Bank Deputies held in Sydney, Australia during October 13-15, 2006. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

పేజీ చివరిగా అప్డేట్ చేయబడిన తేదీ: