Navin Bhatia*

The mechanism of lending through Self Help Groups (SHGs) has gained wide popularity during the last few years and has been adopted as an important strategy by banks for lending to the poor. Despite tremendous growth in the number of SHGs linked to banks, their sustainability has not been subjected to detailed analysis. This paper is based on a State-level study conducted during 2005-06 to review the present status of SHGs, which were linked to banks till March 1998 under the SHG bank linkage programme. The paper introduces the concept of SHGs and portrays their status on various parameters such as continued existence, membership, meetings held, leadership, savings made and loans obtained, loan utilisation and repayment record.

JEL Classification : G 21, G 29

Keywords : Microfinance, SHG and Others.

Introduction

Provision of credit to the poor has remained a formidable challenge for the banking system in India. Various measures such as nationalisation of major banks, massive branch expansion, formation of Regional Rural Banks (RRBs), introduction of directed lending under the priority sector concept and specialised anti-poverty programmes have been taken in this direction during the past. The latest innovation in delivery of credit to the poor has been through the mechanism of Self Help Groups (SHGs).

This paper provides a very brief theoretical concept of SHGs in Section I. While Section II gives the rationale of the study, Section III is devoted to the major findings. At the end, Section IV lists the issues that have emerged from the study and makes certain suggestions.

Section I Concept of SHGs

An SHG is a small group of about 20 persons from a homogeneous class, who come together voluntarily to attain certain collective goals, social or economic. The group is democratically formed and elects its own leaders. The essential features of SHGs include members belonging to the same social strata and sharing a common ideology. Their aims should include economic welfare of all members. The concept of SHGs is predominantly used in the case of economically poor people, generally women, who come together to pool their small savings and then use it among themselves.

It has been the experience that the SHGs are generally formed through the intervention of a facilitating agency. The non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) have traditionally had a history of promoting SHGs. However, over time, SHGs have come to be promoted by Government agencies, banks and also by federations of SHGs themselves.

The SHG members meet at fixed intervals, generally weekly, fortnightly or monthly and collect their savings of a predetermined amount at these meetings. The pooled savings are then used to make small interest bearing loans among themselves. The members who borrow the money have to return the same in weekly, fortnightly or monthly instalments at predetermined rates of interest. The group is solely responsible for determining its periodical saving rate, internal lending policy as well as interest rates.

This process helps group members imbibe the essentials of financial intermediation such as prioritising the needs, fixing terms and conditions, and maintaining accounts. They also learn to appreciate that resources are limited and have a cost. Over a period of time, the groups learn to handle larger sums of money. During this period, the group is also encouraged by the facilitator to open a savings bank account with a bank. If the group transactions go on smoothly for a period of six months or more, it is a signal that the group has matured. If after that stage the group is in need of amounts of money larger than it can generate through its internal funds, the external facilitator

encourages the group to seek loan from a bank. The bank sees the group and on being satisfied with its credentials, grants loan to it. The process of linkage of the SHG with a bank begins when the bank opens its savings bank account. After watching the operations in the account for some time and being satisfied with the credentials of the group, the bank considers the group for lending purposes at the request of the group. The group is eligible for borrowing from the bank in a multiple of its savings. The bank lends to the SHG, which, in turn, gives loans to its members in accordance with the group’s policy. At this stage the group is said to be credit linked to the bank. In common parlance, the SHG is stated to be linked to the bank when it avails credit facilities from the bank. The loan is granted in the name of the SHG and all members of the group are collectively responsible for the repayments to the bank. These loans have no collateral security as group cohesion and peer pressure act as security for the bank loan.

SHG bank linkage programme

The concept of linking SHGs to banks was launched as a pilot project by National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) in 1992. The pilot envisaged linking of just 500 SHGs to banks. By the end of March 1994, 620 SHGs had been linked to banks. The success of the pilot led to its transformation into the SHG bank linkage programme with an ever-increasing number of banks and NGOs participating therein. From modest beginnings in 1992, the SHG bank linkage programme spread rapidly and in just over a decade had emerged as the single largest microfinance programme in the world.

At the end of March 2006, its coverage extended to 583 districts located in 31 States and Union territories. Over 22.38 lakh SHGs had been linked to banks and cumulative loans of Rs 11,397.54 crore disbursed under the programme1. Besides the participation of 4,896 NGOs and other agencies, a total of 44,362 branches of 547 banks were involved in lending under the programme. Women’s groups formed over 90 per cent of the SHGs.

Over a period of time, three different models of lending have emerged under the programme. In Model 1, the bank takes the initiative in forming the groups, nurturing them, opening their savings accounts and then finally providing credit to them. In Model 2, while facilitating agencies like NGOs, government agencies or community based organisations take the lead in forming groups and nurturing them, they are provided savings and credit facilities by the banks. In Model 3, the NGOs, which have promoted and nurtured the groups also act as financial intermediaries. Under this model, the banks lend to these intermediaries for onward financing to the groups or their members. In some cases, the promoting NGOs organise the SHGs into federations, which then take on the role of financial intermediaries. Data published by NABARD reveals that Model 2 has proved to be the most popular. At the end of March 2006, 74 percent of the SHGs linked were under this model; Model 1 and Model 3 accounted for 20 per cent and 6 per cent of the SHGs respectively.

Despite the phenomenal growth under the programme, certain areas of concern continue to persist. First, the focus on achievement in terms of numbers has resulted in the qualitative aspects of the SHGs not getting the deserved attention. Second, there remains a strong regional bias towards the southern States. As at the end of March 2006, while Andhra Pradesh, the State with the largest share among the southern States, accounted for 26.2 per cent of the total SHGs and 38.1 per cent of the total loans disbursed, Rajasthan, the State with the largest share of SHGs in the northern region, accounted for only 4.4 per cent of the SHGs and just 2.1 per cent of the total loans disbursed. Third, the quantum of loan granted per SHG continues to be very low. In March 2006, the amount was Rs 37,582 for new loans and Rs 62,949 for repeat loans to existing SHGs. Considering that on an average an SHG has 14 members, the per capita loan amount in March 2006 was Rs 2,684 for new loans and Rs 4,496 for repeat loans. Fourth, the issue of sustainability of SHGs has also not been highlighted. Only since 2001, NABARD has been publishing data regarding the number of SHGs provided with repeat bank credit. These data reveal that the percentage of SHGs getting repeat bank credit has remained quite low, indicating that most SHGs have had access to bank credit on only one occasion.

Section II

The Study

A review of existing literature revealed that little is known about the sustainability of SHGs, how long they last, and how they and the scale of their transactions change over time. The study was planned by the investigator in the light of the concerns highlighted in Section I and in order to address the gap indicated above. In the present study, the investigator attempted revisiting the SHGs that had been linked several years ago and portraying their present status. The SHGs, which were linked to banks till March 1998, were taken up for the study. In view of the limitations of time and resources, it was decided to restrict the study to only one State. Since the southern states have the maximum number of SHGs, most studies on SHGs have been carried out in those States. It was, therefore, decided to leave them out. The State of Rajasthan was purposively selected for the study as it is the largest State of the country and has the maximum number of SHGs among all the States of the northern region.

Data obtained from NABARD revealed that 245 SHGs were linked to banks in Rajasthan at the end of March 1998. These SHGs were spread over 12 districts of the State. However, 96 per cent of these SHGs (235) were from seven districts, viz., Hanumangarh (95), Udaipur (74), Alwar (30), Ajmer (10), Sawai Madhopur (10), Jodhpur (8) and Chittorgarh (8). The remaining five districts accounted for only 10 SHGs amongst them.2 Therefore, it was decided to cover 235 SHGs in the above seven districts for the study.

The study was based on both primary and secondary data. While secondary data were obtained from NABARD and controlling offices of banks, primary data were collected from 44 SHGs, 12 bank branches, 65 SHG members and 5 NGOs.3 Data collection was carried out between December 2005 and April 2006 through pre-designed schedules and personal interviews with bankers, SHG members and chief functionaries of NGOs. The following paragraphs present the findings of the study and make certain suggestions on the issues emerging therefrom.

Section III Major Findings

(a) Status of linkage

Women’s groups formed less than half (46 per cent) of the SHGs linked to banks by the end of March 1998, as compared to a share of 78 per cent at the national level. A majority of the SHGs (58 per cent) were formed by NGOs and linked to banks under the more popular Model 2 of linkage. The remaining SHGs had been formed by a bank and linked to its branch under Model 1 of linkage. As against a national share of only 18 per cent of the total SHGs linked, Model 1 of linkage occupied a share of 42 per cent in the State.

The spread of SHGs as well as existence of NGOs varied greatly among the districts. While there was an established NGO and a formal SHG federation in existence in Alwar district, in Ajmer district, there were no NGOs worth their name. In Hanumangarh district, all the SHGs had been promoted and financed by a single bank under the Model 1 of linkage while Model 2, where groups were promoted by NGOs, was adopted for linkage by banks in all the remaining districts. In Hanumangarh district, there was a preponderance of male groups while female groups dominated in all other districts. The nature and linkage of groups in this district was also different from other SHGs: each group was composed of five members, there was no internal lending, loans were granted in the names of individuals and members were not required to visit the bank branch.

(b) Number of SHGs traced and existing

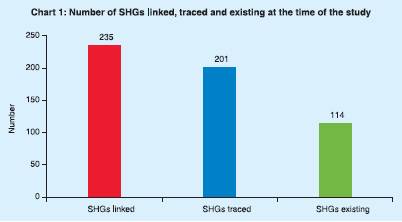

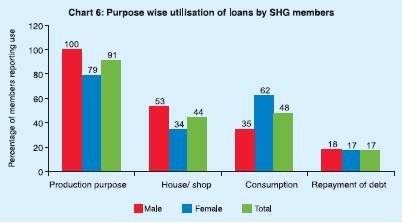

Out of the 235 SHGs linked to banks, the records of only 201 SHGs (85.5 per cent) could be traced out. Despite all efforts made, details of the remaining SHGs were not available, either with NABARD or banks. There is a strong possibility that these SHGs have ceased to exist. In any case, they have, for all practical purposes, been forgotten and written off from the banking system. Further, out of the total SHGs linked to banks, 114 (48.5 per cent) were still in existence at the time of the study. The position is depicted graphically in Chart 1.

It may be seen that at the State level, just less than half of the SHGs that were linked up to March 1998 continued to exist. However,

significant differences were noticed at the district level, both in terms of SHGs traced and SHGs existing. While in Hanumangarh and Sawai Madhopur districts, all the linked SHGs could be traced, on the other hand, in Ajmer district, only 20 per cent of the SHGs could be traced. Similarly, in Hanumangarh and Alwar districts, while 66 and 60 per cent of the SHGs were found to be still in existence, no SHG of the period selected for the study was found existing in Ajmer and Jodhpur districts.

The district-wise position of SHGs linked, traced and in existence is graphically depicted in Chart 2.

The principal reason for the high rate of existence of SHGs in Hanumangarh and Alwar districts was the presence of a strong support system by the promoting organisations. Oriental Bank of Commerce (OBC), the bank that had promoted the SHGs in Hanumangarh district was itself the financing institution and was able to keep a constant watch on them due to its system of weekly meetings firmly in place. In Alwar district, while the NGO that had promoted the SHGs (PRADAN) had largely withdrawn from the area, an SHG federation called Sakhi Samiti had taken over its functions. The regular meetings of Sakhi Samiti went a long way in providing guidance and continuity to the SHGs.

The main reasons for disintegration of groups could be classified under two categories, viz., those pertaining to group dynamics and those external to the group. The reasons relating to group dynamics were: (a) internal conflict and rivalry among the group members; (b) leadership issues within the group; (c) inability to conform to group discipline; (d) members in a hurry to obtain loans; and (e) more loans taken by members as compared to their repaying capacity.

The principal reasons external to the groups were:

(a) continuing drought conditions in the villages leading to migration of some group members; (b) inadequate support and guidance provided by the promoting NGO; and (c) winding up of the promoting NGO itself.

It was evident that the role and responsibility of the promoting organisation was very crucial to the sustainability of the SHGs. It was observed that where the promoting NGO was sincere and committed in its endeavours, the groups had a greater tendency to sustain and mature. However, where the NGO itself lacked the vision and long-term relationship with the SHGs, the groups disintegrated.

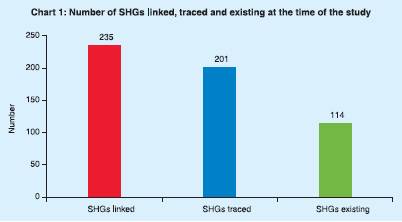

(c) Sex-wise composition of SHGs traced and existing

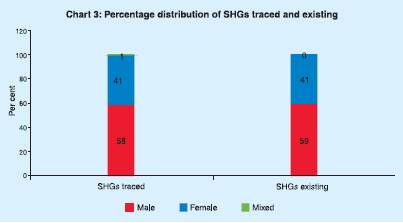

The sex-wise analysis of data pertaining to SHGs traced and existing, given in Table 1 and Chart 3, reveals that there was

Table 1: Sex-wise composition of SHGs traced and |

existing at the time of the study |

Name of |

Number of SHGs traced |

Number of SHGs existing |

district |

Male |

Female |

Mixed |

Total |

Male |

Female |

Mixed |

Total |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ajmer |

– |

2 |

– |

2 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Alwar |

– |

24 |

– |

24 |

– |

18 |

– |

18 |

Chittorgarh |

1 |

7 |

– |

8 |

– |

1 |

– |

1 |

Hanumangarh |

91 |

4 |

– |

95 |

61 |

2 |

– |

63 |

Jodhpur |

– |

3 |

– |

3 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

S. Madhopur |

3 |

9 |

– |

12 |

2 |

2 |

– |

4 |

Udaipur |

21 |

34 |

2 |

57 |

4 |

24 |

– |

28 |

Total |

116 |

83 |

2 |

201 |

67 |

47 |

– |

114 |

|

(58) |

(41) |

(1) |

(100) |

(59) |

(41) |

|

(100) |

Note : Figures in parenthesis show percentage to total number of SHGs. |

practically no difference between the sex-wise distribution of SHGs traced and existing.

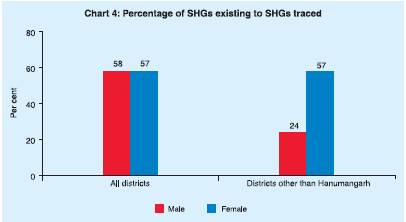

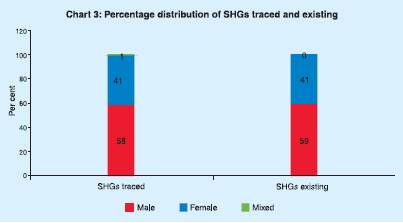

In both the cases, female groups formed 41 per cent of the total SHGs. Data further reveals that out of 116 male groups traced, 67 (58 per cent) were in existence while out of 83 female groups traced, 47 (57 per cent) were in existence. Thus, at the State level there was almost no difference between the sex-wise existence of SHGs as a

percentage of SHGs traced. This may lead to the inference that there was no difference on account of sex in the existence of groups over a period of time. However, the same was not borne by closer analysis of data and field interactions during the study.

It may be noticed that the presence of Hanumangarh district, with its almost all male groups, has led to distortion of the picture somewhat. If SHGs other than those belonging to Hanumangarh district are taken into account, it was found that only 24 per cent of the traced male groups continued to exist. The corresponding figure for female groups was 57 per cent. Thus, by excluding Hanumangarh district, while there was no change in the percentage for female groups, the percentage for male groups showed a significant decline (Chart 4).

These figures reveal that, barring SHGs in Hanumangarh district, male SHGs had a greater mortality rate than female SHGs. This feature was highlighted most significantly in Udaipur district where male, female and mixed groups were all in existence. In that district, the mortality rate was cent per cent in case of mixed groups, 81 per cent in the case of male groups and only 29 per cent in the case of female groups.

Hanumangarh district proved an exception as all the SHGs linked were under Model 1 of linkage where the bank promotes the groups

and also links them. Since this district also accounted for the largest number of SHGs at that time, it resulted in a masking effect on the figures presented above.

It was clearly evident that male SHGs required a greater degree of supervision than female SHGs. Since that level of supervision was in-built in the Hanumangarh model of OBC, the male SHGs promoted in that district sustained to a greater extent over a period of time. In the case of other SHGs, which had been promoted by NGOs, the same level of supervision and monitoring provided to all SHGs resulted in a greater survival rate of female SHGs. The functionaries of NGOs confirmed the above perception in field interactions. It was also revealed that NGOs were in the process of gradually moving away from male SHGs and devoting increasing attention to female SHGs. Even OBC, which had pioneered male groups in the early 1990s in Hanumangarh district, had moved towards forming an increasing number of female groups in the subsequent years.

Field interactions with functionaries of NGOs revealed that better survival rate of female groups was primarily due to the feminine psyche, which placed an increased importance towards repayment ethics and loan utilisation in the overall interest of the family rather than their personal interests. Furthermore, fewer conflicts over leadership issues were stated to be observed in female groups.

(d) Membership of SHGs

Under the SHG bank linkage programme, the number of members in a group is usually kept between 15-20 members. This number is considered ideal for group cohesion and stability and for exerting peer pressure on the members. However, under the Grameen model of lending, which was adopted by OBC, the number of members is pegged at five. Both models were in existence in the State. The study revealed a decline in the membership of SHGs over a period of time. It was found during the study that in Hanumangarh district, only 48 per cent of the groups had the same number of members as at the time of their formation. The average membership of the 63 SHGs functional at the time of the study had come down from 5.0 to 4.1.

Interestingly, the decline in membership resulted in two ‘SHGs’ being left with a lone member each while four others were left with only two members each. Thus, these entities, although appearing as SHGs in bank records, were no longer groups in the true sense.

Data obtained from selected SHGs of Alwar, Sawai Madhopur and Udaipur districts also reveals decline in membership (Table 2). Data reveal that while there was a decline of 18 per cent in the membership of SHGs in Hanumangarh district, the decline was 21 per cent in the membership in the three other districts. Thus, over a period of time, the membership of SHGs had come down by about a fifth of their original numbers.

While a decline in the number of members of a group may not by itself be seen as a negative feature, it definitely reveals chinks in the solidarity of the group. This reflects on the quality of the group, which is again dependent on the credentials of the promoting organisation. The lesser decline in the number of members in case of SHGs in Hanumangarh district could be attributed to the fact that the bank had promoted these groups while the SHGs in other districts were promoted by various NGOs. The closer monitoring in case of Hanumangarh district, largely due to the weekly meeting system, could be responsible for the lesser decline in membership. It was also observed that there was a practice of replacement of members of SHGs in all the districts. New members were often included as group members in place of members who had dropped out. However, this practice could also not curb the decline in membership over a period of time.

Table 2: Average membership of SHGs, |

initially and during the study |

Name of district |

Number of SHGs |

Average initial |

Average membership |

|

|

membership |

during the study |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Alwar |

5 |

15.0 |

11.8 |

Sawai Madhopur |

3 |

18.0 |

16.1 |

Udaipur |

7 |

17.7 |

13.4 |

Total |

15 |

16.9 |

13.4 |

(e) Meetings held and attendance

The position of meetings held and attendance therein was collected for the 44 SHGs, which were still in existence during the study by interacting with some of their members. In 40 of the 44 SHGs (91 per cent), it was reported that the meetings were being held regularly without fail. The remaining SHGs reported that sometimes a few meetings were being skipped or two or three meetings combined into one. The meetings were being held at a fixed place and time. The venue was generally the house of one of the members of the SHG, generally among the office bearers, or at a public place like a school compound. In Hanumangarh district, the meetings were taking place on weekly basis as per the provisions under the Grameen Project. Similarly, weekly meetings were taking place in Alwar district as required under the Sakhi Samiti rules. In other districts, fortnightly or monthly meetings were being held.

As regards attendance at meetings, it was reported that the same varied over time. While most members attended the important meetings, at certain times (such as marriage season, harvest time, etc.) the attendance was lower. The position of average attendance at the SHG meetings held over the last one year is presented in Table 3.

It may be seen that in over three-fourths of the SHGs, the average attendance at meetings was over 75 per cent. It was observed that a practice of proxy attendance was in vogue in several SHGs. A member who was unable to attend a meeting would send his saving amount and loan instalment through another member. Such a member would be treated as present for the meeting.

Table 3: Average attendance during the last one year at |

meetings of SHGs |

(N = 44) |

Attendance at meetings |

Number of SHGs |

Percentage |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Over 90 per cent |

5 |

11 |

Over 75 and upto 90 per cent |

30 |

68 |

Over 60 and upto 75 per cent |

7 |

16 |

Upto 60 per cent |

2 |

5 |

In 35 of the SHGs (80 per cent), there were provisions for levying penalties for not attending the meetings. The amount of penalty was generally Rs 5 to Rs 10 per person for not attending a meeting. While the fines were imposed in most SHGs, only 9 per cent of the SHGs reported that the fines were not being collected.

The reasons given by members for not attending the meetings were being out of the village for work or business, being busy with household activities, religious or other functions in the family, and nothing much being done at the meetings. It was observed that the office bearers of the SHGs were most particular in attending the meetings. Members who had to take loans also made it a point to attend the meetings where their loan proposals were to be discussed.

(f) Leadership

Conceptually, the SHGs should provide for grooming for leadership skills among the members. In Hanumangarh district, where the SHGs comprised only five members, the issue of leadership was not found to be of much relevance. It was learnt that at the time of formation of groups, the leadership issue was important as the group leader was to get the last priority in obtaining loan from the bank. With the passage of time and after several loan cycles, the issue was not of concern to the members. Moreover, in a system where loans were granted to individuals, the role of the leader was reduced to a great extent.

In the remaining districts, it was observed that there had been only marginal and cosmetic changes among leaders of SHGs. In most of the SHGs, the leaders at the time of the study were the same as at the time of formation of groups. Even where there was a change in the leader, the same was largely cosmetic such as the secretary becoming the president or the treasurer assuming designation of secretary. In general, the group leadership had remained vested in the same two or three persons among the group during this time span. Perhaps the time span of seven to ten years was not enough for new leadership to emerge.

When asked about this aspect, the members stated that their leaders were generally performing well and they felt no need to change them. Although anecdotal evidence referred to misuse of position by leaders in several groups leading to collapse of groups, the existing group members seemed relatively complacent in this regard. Perhaps the implicit faith in leadership by the group members was one of the factors responsible for sustaining the groups. Furthermore, among the reasons mentioned for disintegration of groups, leadership issues figured prominently. Hence, SHGs with leadership disputes would have either ceased to exist or the dissatisfied members would have broken away to form new groups. Consequently, the leadership issues in existing SHGs were minimal and not very significant.

It was observed that group leaders generally had a higher status in the groups and often belonged to relatively well-off families as compared to other members. Group leaders generally were also more articulate, possessed higher education level and had more exposure to the outside world than the other group members. A few group leaders had participated in fairs, workshops or exposure visits conducted by their respective NGOs or NABARD.

(g) Group savings

Regular saving by group members is among the core principles of SHGs. The study observed that group members were generally adhering to the saving principle in all the SHGs. In 38 of the 44 SHGs (86 per cent) regular savings were being made at the periodicity prescribed. In the remaining SHGs, savings were being made but not at the prescribed periodicity. In these SHGs, there were occasional cases of several members depositing savings in lump sum.

In two districts, viz., Alwar and Hanumangarh, the prescribed periodicity of savings was on weekly basis. In the remaining districts, the group members were making their savings on monthly basis. At the time of formation of groups, the individual savings varied from Rs 5 to Rs 10 per week in Alwar and Hanumangarh districts and from Rs 10 to Rs 50 per month in the remaining districts. The present rate of savings by members had gone up from those amounts. They now varied between Rs 10 to Rs 50 per week and from Rs 50 to Rs 200 per month in the respective districts.

Provision for fines in case of non-payment of prescribed savings existed in 35 SHGs (80 per cent). The range of fine for default varied from Rs 5 to Rs 10. In most SHGs, the fines were being collected religiously. In only two SHGs (5 per cent) it was reported that fines existed only on paper and were not being levied. It was observed that the fine amounts were rather low and not a deterrent for not depositing the savings in time. However, the provision of fines for not depositing the savings in time acted as a sort of reminder to the members. There was also a degree of social stigma attached to not depositing the saving regularly; hence about 90 per cent of the members generally made their savings in time. Only in a miniscule number of cases, it was reported that the members were so poor that they could not deposit even the minimum savings amount regularly. In very few cases, the savings were made with arrears on account of the members being away from the village in connection with their work.

In the SHG concept, the savings of members are supposed to be deployed towards internal lending amongst the group members. However, under the Grameen model being followed in Hanumangarh district, the savings of members are deposited in the bank and members are not supposed to withdraw the amount. As a result, group members had built up respectable savings over a period of time. As soon as the group savings reach Rs 5,000, the bank makes fixed deposits of Rs 1,000 each in the names of the individual members (assuming that all members have saved equally). In the process, the total savings of the 63 SHGs existing at the time of the study with the bank had accumulated to Rs 22.21 lakh. The average deposit per member worked out to Rs 8,609.

In other districts, where the group savings were being utilised towards internal lending among group members, some SHGs had built up savings bank deposits in the range of Rs 20,000 to Rs 40,000. Some SHGs were withdrawing the entire amount at periodical intervals and distributing the same in proportion to the savings made by the members. Since the amounts were being withdrawn whenever required, it was not possible to get figures for aggregate savings made by SHGs. However, interactions with field functionaries of NGOs revealed that the total savings of the SHGs that had been in existence for several years were substantial. As a very rough estimate, a member saving Rs 50 per month for eight years would have saved Rs 4,800. A group having 15 such members would have had a total saving of Rs 72,000 during this period.

It was observed that the group savings acted as a source of strength and confidence for the members. Several members, during their interactions with the investigator, expressed pride and happiness at the savings habit that they developed as a result of their becoming members of SHGs. The accumulated savings possessed by the SHG in their accounts were in many cases of an amount that they had never imagined would be possible in their lifetime.

(h) Repeat finance to SHGs

One of the critical issues in sustainability of SHGs is their access to repeated doses of finance. It is generally supposed that over a period of time, the SHGs would access and absorb larger doses of credit. This aspect was examined during the study.

In Hanumangarh district, where all the SHGs were covered under the OBC’s Grameen Project, individual group members were the recipients of the loans directly from the bank. Therefore, the position regarding the number of times loans were availed was obtained in respect of selected individual members in that district. In all the other districts, banks disbursed the loans in the names of SHGs; hence the position of repeat finance was considered for the SHGs.

The position regarding number of times individual SHG group members obtained loans from banks in Hanumangarh district is shown in Table 4. It may be seen that over 70 per cent of the members had taken loans on three or more occasions from the bank. As all SHGs covered in the study had been in existence for nearly a decade, the coverage of loans could be considered adequate. It was also observed that over half of the members who reported having taken loan once or twice were those who had joined the SHGs at a later date.

Table 4: Number of times SHG members in Hanumangarh |

district availed loans from banks |

(N=28) |

Number of times |

Number of persons |

Percentage to total |

loan availed |

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

Once |

3 |

11 |

Twice |

5 |

18 |

Thrice |

14 |

50 |

More than thrice |

6 |

21 |

The position regarding the number of times SHGs in the remaining six districts obtained loans from banks is indicated in Table 5. It may be seen that the largest number of SHGs (39 per cent) had taken only a single loan from the banks while nearly a third of the SHGs (32 per cent) had taken loans on three or more occasions.

It may be noted that the figures in Table 5 are not strictly comparable to those in Table 4 because data in respect of Hanumangarh district pertains to individual members of SHGs and not SHGs themselves. Secondly, the members selected from SHGs in Hanumangarh district all belonged to SHGs that were in existence at the time of the study whereas the SHGs in other districts for whom data have been presented were those which had been traced during

Table 5: Number of times SHGs availed loans from banks |

Name of district |

Number of |

Number of times loans availed |

|

SHGs |

Once |

Twice |

Thrice |

More than thrice |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Ajmer |

2 |

1 |

1 |

– |

– |

Alwar |

24 |

5 |

13 |

5 |

1 |

Chittorgarh |

8 |

7 |

1 |

– |

– |

Jodhpur |

3 |

3 |

– |

– |

|

Sawai Madhopur |

12 |

5 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

Udaipur |

57 |

20 |

15 |

9 |

13 |

Total |

106 |

41 |

31 |

18 |

16 |

|

(100) |

(39) |

(29) |

(17) |

(15) |

Note : Figures in parenthesis indicate percentage to total number of SHGs. |

Table 6: Number of times loans availed by SHGs that |

have ceased to exist |

Name of district |

Number of |

|

Number of times loans availed |

|

SHGs |

Once |

Twice |

Thrice |

More than thrice |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Ajmer |

2 |

1 |

1 |

– |

– |

Alwar |

6 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

– |

Chittorgarh |

7 |

7 |

– |

– |

– |

Jodhpur |

3 |

3 |

– |

– |

– |

Sawai Madhopur |

8 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

– |

Udaipur |

29 |

18 |

8 |

3 |

– |

Total |

55 |

36 |

13 |

6 |

– |

|

(100) |

(65) |

(24) |

(11) |

|

Note : Figures in parenthesis indicate percentage to total number of SHGs. |

the study. It is but natural that those SHGs that had continued to exist would have obtained loans on more occasions than SHGs that ceased to exist.

The data presented in Table 5 has been disaggregated in Tables 6 and 7 according to whether the SHGs had ceased to exist or whether they continued to exist respectively.

Table 7: Number of times loans availed by SHGs that |

continued to exist |

Name of district |

Number of |

|

Number of times loans availed |

|

SHGs |

Once |

Twice |

Thrice |

More than |

|

|

|

|

|

thrice |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Ajmer |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Alwar |

18 |

3 |

10 |

4 |

1 |

Chittorgarh |

1 |

– |

1 |

– |

– |

Jodhpur |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Sawai Madhopur |

4 |

– |

– |

2 |

2 |

Udaipur |

28 |

2 |

7 |

6 |

13 |

Total |

51 |

5 |

18 |

12 |

16 |

|

(100) |

(10) |

(35) |

(24) |

(31) |

Note : Figures in parenthesis indicate percentage to total number of SHGs. |

It may be seen that out of the SHGs that ceased to exist, nearly two-third (65 per cent) had taken only one loan from the banking system. On the other hand, out of SHGs that continued to exist, more than half (55 per cent) had obtained loans on three or more occasions while just one-tenth had obtained a single loan from the banks.

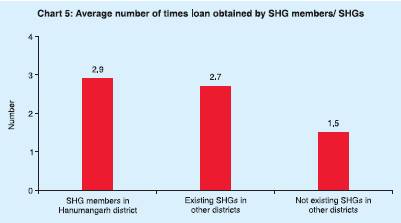

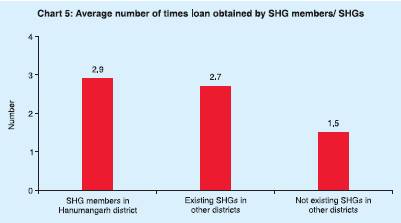

Further data analysis revealed that, on an average, in Hanumangarh district, a member had taken loan 2.9 times. In other districts the average number of times an SHG that had ceased to exist took loan from a bank worked out to 1.5 while the average number of times an existing SHG availed loan from the bank worked out to 2.7 (Chart 5).

Field interactions indicated that there was a greater tendency on the part of the SHGs to crumble during the first two years of their existence. The first loan from the bank was a milestone in the life of an SHG. While in some SHGs the bank loan acted as a binding agent, spurring the members towards greater cohesion and solidarity, in other SHGs, it worked as an instrument of discord resulting in infighting among the members. If the SHG could resolve the issues, which arose subsequent to the first loan from the bank, it would have taken a big stride towards stability.

(i) Quantum of loan taken

One major concern in the context of financing to SHGs has been that the quantum of loan availed has remained rather low. This aspect was examined during the present study.

In Hanumangarh disrict, loans were taken by individual members as per the provisions of Grameen Project, which stipulates a maximum limit on the loan amount. The amount of first loan was Rs 5,000 while subsequent loans were generally for higher amounts. Since almost all members had taken repeat loans, their present loans were in the range of Rs 8,000 to Rs 25,000. Under the Project, the present ceiling for loan was Rs 25,000. The study showed that while over half the members (58 per cent) had present loans between Rs 20,000 to Rs 25,000, another 21 per cent had present loans between Rs 15,000 to Rs 20,000. The average present loan amount came to Rs 19,600 while the average total loan amount came to Rs 31,500.

In other districts, the amount of first loan availed by an SHG generally ranged from Rs 5,000 to Rs 40,000, save a solitary instance where a loan of Rs 89,700 was granted to an SHG in 1995.

In all districts, repeat loans were generally of higher amounts than first loans. The district-wise distribution of SHGs according to the total loans availed by them till the date of the study is shown in Table 8. It may be seen that over a half of the SHGs had availed of

Table 8: Distribution of SHGs according to the amount of |

loan received |

Name of district |

Number of SHGs |

Amount of loan availed (Rs lakh) |

|

|

Up to |

0.50- |

1.00- |

2.50- |

Over |

|

|

0.50 |

1.00 |

2.50 |

5.00 |

5.00 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

Ajmer |

2 |

2 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Alwar |

24 |

9 |

8 |

7 |

– |

– |

Chittorgarh |

8 |

8 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Jodhpur |

3 |

3 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Sawai Madhopur |

12 |

6 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

– |

Udaipur |

57 |

28 |

10 |

9 |

6 |

4 |

Total |

106 |

56 |

19 |

20 |

7 |

4 |

|

|

(53) |

(18) |

(19) |

(6) |

(4) |

Note : Figures in parenthesis indicate percentage to total number of SHGs. |

Table 9: Distribution of SHGs that ceased to exist according |

to the amount of loan received |

Name of district |

Number of SHGs |

Amount of loan availed

(Rs lakh) |

|

|

Up to |

0.50- |

1.00- |

2.50- |

Over |

|

|

0.50 |

1.00 |

2.50 |

5.00 |

5.00 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

Ajmer |

2 |

2 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Alwar |

6 |

3 |

3 |

– |

– |

– |

Chittorgarh |

7 |

7 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Jodhpur |

3 |

3 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Sawai Madhopur |

8 |

6 |

– |

2 |

– |

– |

Udaipur |

29 |

24 |

5 |

– |

– |

– |

Total |

55 |

45 |

8 |

2 |

– |

– |

|

(100) |

(82) |

(14) |

(4) |

|

|

Note : Figures in parenthesis indicate percentage to total number of SHGs. |

loans of up to Rs 50,000. There were only four SHGs that had so far taken loans of over Rs 5 lakh. The maximum total loan availed by an SHG during its existence was Rs 8.84 lakh, availed by an SHG in Udaipur district.

However, if the figures of SHGs that had ceased to exist and SHGs that continue to exist are studied separately, they throw up different results. These are shown in Tables 9 and 10, respectively.

Table 10: Distribution of SHGs that continued to exist |

according to the amount of loan received |

Name of district |

Number of |

Amount of loan availed (Rs lakh) |

|

SHGs |

Up to |

0.50- |

1.00- |

2.50- |

Over |

|

|

0.50 |

1.00 |

2.50 |

5.00 |

5.00 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

Ajmer |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Alwar |

18 |

6 |

5 |

7 |

– |

– |

Chittorgarh |

1 |

1 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Jodhpur |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Sawai Madhopur |

4 |

– |

1 |

2 |

1 |

– |

Udaipur |

28 |

4 |

5 |

9 |

6 |

4 |

Total |

51 |

11 |

11 |

18 |

7 |

4 |

|

(100) |

(21.5) |

(21.5) |

(35) |

(14) |

(8) |

Note : Figures in parenthesis indicate percentage to total number of SHGs. |

The figures show that over four-fifth of the SHGs that ceased to exist (82 per cent) had received loans of up to Rs 50,000. On the other hand, only about a fifth of the SHGs (21.5 per cent) that were in existence had availed of loans of that amount. Over half of the SHGs in existence (57 per cent) had received loan amounts of over Rs 1 lakh. It is clear that the SHGs that continued to exist received higher amounts of loans than those that ceased to exist.

The average loan amount received per SHG in all the three categories revealed wide variations in different districts. District-wise figures in this regard are shown in Table 11. It may be observed that the average loan amount availed by an SHG worked out to Rs 62,136. Furthermore, the average loan for an SHG that continued to exist was nearly three times higher at Rs 173,813. The total average loan amount of existing SHGs as compared with the savings made by these SHGs, indicated that the quantum of loan was roughly 2.4 times of their cumulative savings.

Out of the 65 members contacted during the study, as many as 63 (97 per cent) reported getting of loan from the bank. The average loan availed by members who had obtained bank loans in different districts is given in Table 12. It may be seen that the average loan amount was highest in Hanumangarh district and least in Chittorgarh district. The average loan availed per person from the banks at Rs 15,630 was quite low considering that they had been members of the SHG for

Table 11: Average loan amount received per SHG in |

different districts |

Name of district |

Average loan amount

received per SHG (Rs) |

|

|

All SHGs |

SHGs ceased |

SHGs existing |

|

|

to exist |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Ajmer |

20,000 |

20,000 |

– |

Alwar |

86,625 |

42,500 |

101,333 |

Chittorgarh |

9,375 |

9,375 |

– |

Jodhpur |

25,000 |

25,000 |

– |

Sawai Madhopur |

94,167 |

51,876 |

178,750 |

Udaipur |

137,649 |

37,517 |

241,357 |

Total |

62,136 |

31,045 |

173,813 |

Table 12: Average loan amount received per member |

|

in different districts |

|

Name of district |

Number of members |

Average loan amount (Rs.) |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Alwar |

13 |

14,300 |

Chittorgarh |

3 |

3,750 |

Hanumangarh |

28 |

31,500 |

Sawai Madhopur |

6 |

12,900 |

Udaipur |

13 |

15,700 |

Total |

63 |

15,630 |

around a decade. However, members in districts other than Hanumangarh had also borrowed from the internal savings of the groups on several occasions.

(j) Utilisation of loan

Members reported multiple areas for utilisation of the loan amounts. Table 13 shows the district-wise position in this regard.

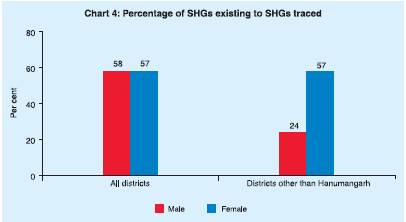

It may be seen that an overwhelming majority (91 per cent) of members reported loan utilisation for productive purposes. Among the production purposes, dairy activity was the most preferred activity and purchase of buffaloes and goats was most common. This was followed by availing finance for various types of shops, among them kirana shops and cycle repair shops being most common. Nearly half (47 per

Table 13: Purpose-wise utilisation of loans by SHG members |

in various districts |

Name of district |

Number of |

Purpose of loan utilisation |

|

members |

Production |

House/ shop |

Consumption |

Debt |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Alwar |

13 |

10 |

7 |

8 |

2 |

Chittorgarh |

3 |

– |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Hanumangarh |

28 |

28 |

15 |

9 |

4 |

Sawai Madhopur |

6 |

6 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

Udaipur |

13 |

13 |

3 |

8 |

3 |

Total |

63 |

57 |

28 |

30 |

11 |

|

(100) |

(91) |

(44) |

(48) |

(17) |

Note : Figures in parenthesis indicate percentage to total number of members. |

cent) the members reported utilising loan amounts for consumption purposes. Among consumption needs, members had utilised the loans on medical needs, wedding of family members, utensils and jewellery.

A very large number of members (44 per cent) utilised loan amounts towards construction or repair of house or shop. Although construction or repair of shop would qualify for production purposes, it was shown clubbed with construction or repair of house as the nature of utilisation of loan was basically different. Furthermore, some members were running their shop or business from the same location as their residence; hence construction or repair of one of those could not be treated separately. Over one-tenth (17 per cent) of the members reported using the amounts towards repaying earlier debts.

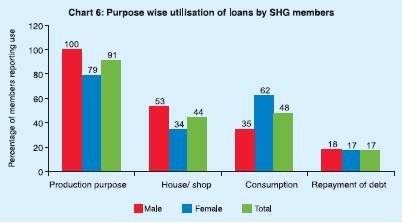

An analysis of the data on utilisation of loans, classified on the basis of sex, shows that while all the male members (100 per cent) reported utilising the loans for productive purposes, just over three-fourths (79 per cent) of the female members did so (Table 14). Furthermore, while only a third of the men (34 per cent) reported utilising loans for consumption purposes, as many as 62 per cent of the women reported so. The position regarding utilisation of loans by SHG members, overall and sex-wise, is depicted in Chart 6.

Field interactions with women SHG members brought out the fact that many women indulged in purchase of jewellery items for their own use or for their children. They looked upon jewellery not only as a cosmetic embellishment but as an avenue for investment or security, to be drawn upon in times of need and crisis.

Table 14: Purpose-wise utilisation of loans by SHG |

members classified on the basis of sex |

Sex |

Number of |

Purpose of loan utilisation |

|

members |

Production |

House/shop |

Consumption |

Debt |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Male |

34 |

34 |

18 |

12 |

6 |

|

|

(100) |

(53) |

(35) |

(18) |

Female |

29 |

23 |

10 |

18 |

5 |

|

|

(79) |

(34) |

(62) |

(17) |

Note : Figures in parenthesis indicate percentage to total number of members of the respective sex. |

(k) Repayment of loans

Prompt and timely repayment of loans has for long been considered the hallmark of lending to SHGs. Several studies have highlighted that repayment in loans granted to SHGs has exceeded 90 to 95 per cent. This aspect was also examined during the course of the study.

In Hanumangarh district, where the loans were granted not in the name of the SHG but in the names of individual members, the repayment record was observed to be good. There was no default in the current loan accounts of all the 28 members contacted during the study. However, a perusal of the current records of the bank revealed that in about 5 per cent of the cases, repayments were not forthcoming as per schedule and the accounts were overdue. It was observed that groups where the membership had reduced to three or less members were more vulnerable to default.

In Alwar district, out of the seven SHG loan accounts still continuing with the original branches, four accounts (57 per cent) were overdue and NPA. In Udaipur district, out of the 21 SHGs continuing to have loan accounts with banks, nine accounts (43 per cent) were irregular and overdue. Out of these, in two accounts the SHGs had ceased to exist and their loan amounts were yet to be repaid.

Furthermore, out of 36 SHG accounts, which were closed at the time of the study, recovery had been irregular and delayed in eight accounts (22 per cent). Even the repayments in some of these accounts had to be re-phased during the period of loan. In Sawai Madhopur district, out of the 12 SHGs that has been credit linked, the accounts of four SHGs (33 per cent) had become NPA. Only two of these SHGs were still in existence. In Chittorgarh district, out of eight SHGs linked, one account (12 per cent) was NPA; the concerned SHG had ceased to exist. In Jodhpur district, out of the three SHG accounts that could be traced, in two of them (66 per cent) the accounts had become NPA before they were settled and closed. In Ajmer district, the repayments in both the SHGs that could be traced had been regular before the accounts were closed.

Thus, the consolidated position in respect of 89 SHGs spread over six districts indicated that in 28 of the SHGs (31 per cent), there were problems relating to repayment of loans. If only the existing SHG accounts are taken into account, the position still worsens with 15 out of 33 accounts (45 per cent) having problems in repayment.

The study thus revealed that the picture of repayment in respect of SHGs linked to banks up to March 1998 was not a rosy one as would have been expected. At the branch level, bankers conceded that several SHG accounts showed signs of irregular repayments. However, where there were sincere NGOs involved, the bankers took recourse to them for pursuing with the SHGs to make repayments regularly. It was observed that the bankers did not make any worthwhile efforts for effecting recovery from recalcitrant SHGs, presumably because of the small sums involved.

Significantly, the repayment record where the bank had itself promoted the SHGs (in Hanumangarh district) was much better than where the SHGs had been promoted by NGOs. In the former case, the bank was directly in touch with the individual SHG members on a weekly basis; hence it resulted in a closer and intimate monitoring of the accounts. In other districts, the bankers relied very heavily on the promoting NGOs for monitoring the accounts

of SHGs. In one of the districts, the banker was ignorant about the location of the SHG and conceded that he had never visited the group. In other districts too, the bankers seldom paid a visit to the SHG after the loan was sanctioned though visits prior to sanction had been made.

Section IV Emerging Issues

The issues that have emerged from the study relate to sustainability of SHGs, loan frequency and size, membership, leadership, repayment of loans, model of linkage, maintaining of database and the life cycle of SHGs. These issues are summarised below, together with certain suggestions.

The large-scale disintegration of SHGs as brought out by the study portends a potential threat to the SHGs bank linkage programme. In order to ensure sustainability of SHGs, the quality of groups formed is of prime importance. Group formation needs to be handled in a professional manner by trained personnel. At the apex level, NABARD should focus on paying increased attention to the promoters of SHGs. In recent years, when Government agencies have ventured into group formation in big way, it is very important that their functionaries are also sensitised about the importance of group quality and sustainability. The banks should undertake due diligence of the promoting organisations before releasing the funds. An initial guideline enunciated by NABARD at the time of launching the Pilot Project stated that the group members should have a feeling of mutual help and should not have come together only for the sake of getting bank finance. This is still relevant and should not be lost sight of in the race to achieve the ever-increasing targets for forming SHGs.

The amount and frequency of loans availed by SHG members may appear to be low but in relation to their savings, it varies between two to three times of the total savings. For the poor persons who have been exposed to bank finance for the first time in their lives, this amount could be considered adequate. However, for SHGs that continue to sustain beyond a certain time period, say five years, the amount of loan should increase considerably to enable members to graduate to the economic activity stage. The time has come for NABARD to formulate a suitable policy for matured SHGs. Both banks and the promoting organisations have to be sensitised about the financial requirements of SHG members after the SHGs reach a degree of maturity. Such members of mature SHGs who desire to graduate to higher levels should have access to guidance and finance to enable them to increase the scale of their operation, either at the individual level or in the group. Smaller groups of up to five persons, out of the original SHG could be considered separately for financing within the scope of SHG lending.

The decline in membership of SHGs over a period of time by about one-fifth should cause some rethinking on this aspect. In Hanumangarh district, where the original groups comprised only five members, the reduced membership had in certain cases reduced the ‘group’ to a single or two members adversely affecting its performance. While the general practice in the context of the SHG bank linkage programme has been to promote groups comprising 15 to 20 members, the desirability of having smaller groups comprising about 10 to 12 members needs to be examined. In the light of performance of five member groups as promoted by OBC under the Grameen Model, there seems to be a case for having smaller groups than the ones presently propagated. Perhaps such smaller groups would result in greater group cohesiveness and solidarity than is in evidence at present.

While leadership issues were among the major cause for disintegration of SHGs, they were not of much consequence once the group had stabilised. Generally, the better educated and socially and economically more advanced among the group members tended to assume the leadership roles in SHGs. The same set of two or three persons continued with the leadership roles within the SHGs. This arrangement had been accepted by the other group members. The time period of less than a decade was perhaps too short for alternative leadership to emerge within the groups.

Problems in repayment of loans by SHGs were quite widespread. Since the amounts involved in these loans at the individual level were not of much significance to the banks, there was a tendency not to take a serious note of irregularities in the repayment schedules of SHGs. However, as the loans to SHGs also had a tendency to slip into the irregular mode more often than not, bankers need to exercise care and caution while dealing with SHGs as they would in case of other borrowers. Besides conducting personal visit to the SHG and due diligence of the promoting NGO before sanctioning loans to the SHGs, the post sanction supervision and monitoring also requires to be carried out seriously. These tasks can be entrusted to the NGOs/ SHGs under the business facilitator and correspondent models in terms of guidelines issued by Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in January 20064.

The better performance of groups in Hanumangarh district on several parameters than the SHGs in other districts may lead to the impression that Model 1 scores over the Model 2 of linkage. However, that interpretation could be flawed. The groups in Hanumangarh district performed better compared to other SHGs due to better and more intensive monitoring through weekly meetings in the presence of the banker and continuous contact through dedicated bank personnel. If the same features could be adopted in Model 2 of linkage by the promoting organisation, the performance could show an improvement. For such an effort, the promoting organisations/ banks would have to redouble their efforts for group monitoring and support. This would no doubt require increase in their costs. Perhaps the banks or NABARD could be persuaded to share a part of this cost of the promoting institutions. The RBI guidelines on business correspondent and business facilitator models could be used to strengthen the NGO mechanism.

There exists an imperative need to set up and maintain a systematic life cycle data-base of all SHGs covered under the SHG bank linkage programme. Although NABARD does maintain figures relating to SHGs promoted and financed under the programme, there is a case for individual SHG level data being available at NABARD at its district level offices. Since the SHG bank linkage is a flagship programme of NABARD, it must possess micro level information relating to the SHGs covered under the programme.

The life cycle of an SHG needs to be studied and understood in detail. The granting of first loan to the SHG should not be viewed as the culmination of the process of linkage (as happens in many cases) but as the first step in the progressive maturing of the group. Unfortunately, the reporting system and the target oriented approach place undue importance to this aspect resulting in complacence on the part of the promoting agencies as well as the banker. This often results in the first signs of problems within the group getting ignored. In order to monitor the progress of the health of SHGs that have been linked to the banking system, all SHGs may be covered by a rating system based on parameters already identified by NABARD. Only those SHGs that secure top ratings may be considered for subsequent doses of funds. A similar rating system may also be made applicable to the promoting organisations.

Notes

1. As per provisional figures for 2006-07, 29.24 lakh SHGs had been linked to banks and cumulative loans of Rs. 18,041 crore disbursed under the programme (Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India, 2006-07).

2. These districts, with the number of SHGs in brackets, were Kota (4), Bharatpur (3), Dausa, Banswara and Jhunjhunu (1 each.)

3. The district-wise break-ups were as follows:

SHGs: Alwar (5), Chittorgarh (1), Hanumangarh (28), Sawai Madhopur (3) and Udaipur (7); Bank branches: Alwar and Udaipur (3 each), Sawai Madhopur (2), Chittorgarh, Hanumangarh, Ajmer and Jodhpur (1 each);

SHG members: Alwar (15), Chittorgarh (3), Hanumangarh (28), Sawai Madhopur (6) and Udaipur (13); NGOs: Udaipur (2), Alwar, Chittorgarh and Sawai Madhopur (1 each).

4. Circular DBOD.No. BL.BC. 58/22.01.001/2005-06 dated January 25, 2006 (available on website www.rbi.org.in).

Select References

Basu, Kishanjit and Krishan Jindal (2000), Microfinance Emerging Challenges, Tata McGraw Hill Publishing Company Ltd, New Delhi.

Fisher, Thomas and M.S.Sriram (2002), Beyond Micro-Credit: Putting Development Back into Micro-Finance, Vistaar Publications, New Delhi.

NABARD (2000), NABARD and microFinance 1999-2000.

NABARD (2006), Progress of SHG-Bank Linkage in India 2005-06.

* The author is Deputy General Manager, Rural Planning and Credit Department, Reserve Bank of India, Central Office, Mumbai. This paper is an abridged version of the findings of the study conducted by him under the supervision of Prof Abhay Pethe, Professor of Economics, University of Mumbai during the sabbatical granted to him by the Bank. The views expressed are those of the author and not of the institution to which he belongs.

|

IST,

IST,