IST,

IST,

Report of the Expert Committee to Review the Extant Economic Capital Framework of the Reserve Bank of India

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has developed an Economic Capital Framework (ECF) to provide an objective, rule-based, transparent methodology for determining the appropriate level of risk provisions to be made under Section 47 of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. The framework was developed in 2014–15, and while it was used to inform the risk provisioning and surplus distribution decisions for that year, it was formally operationalized in 2015–16. The ECF was supplemented by a Staggered Surplus Distribution Policy (SSDP) in 2016-17 to smoothen the cyclicality in RBI’s economic capital and incorporate a certain degree of flexibility in surplus distribution. 2. As decided by the Central Board of the RBI in its meeting held on November 19, 2018, the RBI, in consultation with the Government of India (Government), constituted an Expert Committee to review the extant ECF of the RBI. Shri Subhash Chandra Garg, the then Secretary, Department of Economic Affairs, was initially a member of the Committee. Subsequently, with the appointment of Shri Rajiv Kumar, Finance Secretary, the composition of the Committee is as under:

The terms of reference (ToR) of the Committee are given below: 2.1 Keeping in consideration (i) statutory mandate under Section 47 of the RBI Act that the profits of the RBI shall be transferred to the Government, after making provisions ‘which are usually provided by the bankers’, and (ii) public policy mandate of the RBI, including financial stability considerations, the Expert Committee would:

2.2 To suggest an adequate level of risk provisioning that the RBI needs to maintain; 2.3 To determine whether the RBI is holding provisions, reserves and buffers in surplus / deficit of the required level of such provisions, reserves and buffers; 2.4 To propose a suitable profits distribution policy taking into account all the likely situations of the RBI, including the situations of holding more provisions than required and the RBI holding less provisions than required; 2.5 Any other related matter including treatment of surplus reserves, created out of realized gains, if determined to be held. The Memorandum of Constitution of the Expert Committee is at Annex I. 3. The Committee held eleven meetings during the course of its deliberations. The first meeting was held on January 8, 2019. As the Committee was required to submit its report within a period of 90 days from the date of its first meeting, an extension was granted by the RBI. 4. These meetings were also attended by Dr. Deepak Mohanty (Executive Director, RBI), Shri Amit Agrawal (Joint Secretary, Department of Financial Services) and Dr. Shashank Saksena (Adviser, Department of Economic Affairs) as special invitees in light of their expertise and long-standing association with the ECF. 5. Shri Rohit P. Das (General Manager, RBI) was the nodal officer to the Committee and provided outstanding secretariat support to the Committee. 6. The Committee expresses its appreciation to Dr. Deepak Mohanty, Shri Amit Agrawal, Dr. Shashank Saksena and Shri Rohit P. Das for the extensive contribution and support provided to the Committee. 7. The Committee expresses its appreciation to the Government officials Dr. C. S. Mohapatra (Additional Secretary, DEA), Shri Abhishek Anand (Deputy Director, DEA), Shri Shubham Bhatia (Officer on Special Duty, DFS) and Ms. Meetu Aggarwal (Officer on Special Duty), who extensively supported the Committee. 8. The Committee records its appreciation to the supporting RBI team comprising of Smt./Shri Minal A. Jain, Saurabh Aggarwal, Kaustubh Jambhulkar, Ashish Gupta, Sangeetha Mathews, Dr. N. K. Unnikrishnan, Dr. D. Bhaumik, Indranil Bhattacharya, Shriti Das, Jaikish, Manoranjan Padhy, Indranil Chakraborty, S. S. Ratanpal, Purnima S. Lakra, Dr. S. Gayen, Dr. Jai Chander, Dr. Saurabh Ghosh, Shailaja Singh, Savitha Rajeevan, Meenakshi S. Seet, Pradeep Kumar and Saket Kumar. 9. The Committee expresses its appreciation to RBI, New Delhi for providing logistic support. 10. The Committee finalized its recommendations after, inter alia, taking an overview of the role of the central bank’s financial resilience, reviewing cross-country practices, and assessing the impact of RBI’s public policy mandate and operating environment on its balance sheet and risks. 11. Finally, the Committee would like to thank Shri Shaktikanta Das (Governor, RBI), for entrusting it with this responsibility.

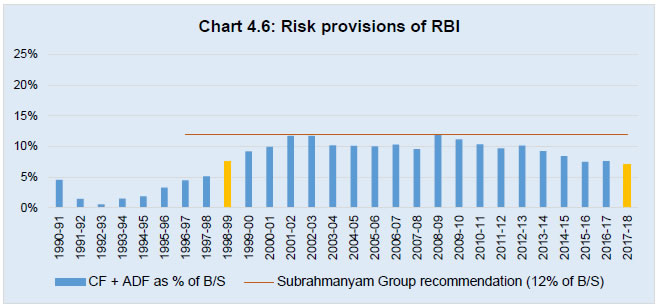

1. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is one of the pioneers in the area of central bank capital, starting with the Subrahmanyam Group which submitted its report in early 1997. This was followed by the Thorat Committee in 2004 (recommendations of which were not accepted), the Malegam Committee in 2014 (recommendations of which were accepted) and the Economic Capital Framework (ECF) which was developed between 2014 - 2015 and operationalized by the RBI in 2015-16, so as to operate concurrently with the Malegam Committee’s recommendations which were valid for a three-year period, i.e. 2013-14 to 2015-16. 2. This periodic assessment indicates the importance that the Government of India (Government) and the RBI have placed on finding the right balance between the opportunity cost of central bank capital vis-à-vis the socio-economic cost and the negative externalities of having an undercapitalized central bank, making it imperative that a holistic and comprehensive perspective be taken based on what is in the best interest of the country as a whole. Central bank capital and its role in monetary and financial stability 3. Central banks do not require capital to carry on operations, as being the managers of domestic liquidity, they can do so simply by printing currency/ creating liquidity. The Committee recognised that central banks require financial resilience to absorb the risks that arise from their operations and the delivery of their public policy mandate of buffering the economy from monetary shocks and financial stability headwinds (by virtue of them being the monetary authority as well as LoLR). Emerging Market and Developing Economy (EMDE) central banks have an additional role of managing external stability in the face of volatile capital flows, and the spillover effect of monetary policy changes by Advanced Economies (AE) central banks. 4. The Committee is of the view that there is an important link between central banks’ financial resilience and its policy efficacy. A survey of international literature also reveals that this is the predominant view in the academia and the central banking community. Central banks’ unique risk environment and their risk management frameworks 5. Central banks are exposed to some similar risks as commercial banks, though their operating risk environment is also unique on account of the following:

6. Among central banks, given the considerable variation in their roles and responsibilities, the environments they operate in, their financial relationship with the Sovereign and their accounting frameworks, there is no internationally laid down risk capital framework for central banks. Central banks, therefore, develop and adapt risk management frameworks to their own specific conditions and requirements. This also means that international comparisons will only reveal global trends and averages, but not a generally agreed international norm. 7. The broad approach that most central banks have followed is to draw a distinction between risks arising out of monetary policy/ financial stability operations and other risks. Many of the central banks actively monitor the risks arising from their monetary policy operations, but do not seek to limit or offset those risks for reasons relating to policy efficacy, while risks arising from non-monetary operations are actively managed. Institutional mechanisms are put in place to ensure that financial resilience is appropriate to absorb the impact of policy risks. Review of central banking practices 8. The Committee was informed by a cross-country analysis of 53 central banks and the salient observations are outlined below.

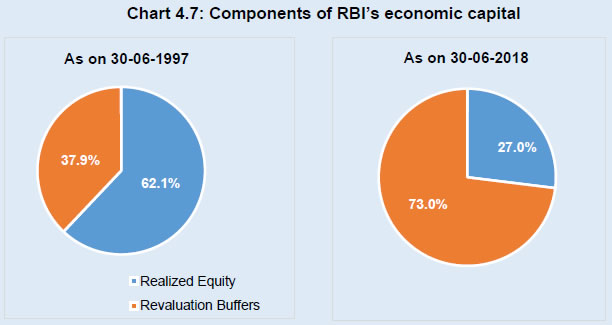

Comparison of central banks’ risk buffer levels 9. The Committee noted that the RBI had an overall fifth rank in 2018 at 26.8 per cent of its balance sheet with respect to central banking economic capital, largely emanating from revaluation balances accumulated by rupee depreciation vis-à-vis the US dollar. Among the EMDEs, the RBI’s position was fourth in 2018, with the other concerned central banks also having large revaluation buffers. 10. The RBI’s realized equity (the component which is actually determined by the central bank’s management) was 7.2 per cent of its balance sheet in 2018 as revaluation balances account for 73 per cent of RBI’s economic capital. 11. The Committee noted that drawing definitive conclusions from simple comparative analysis with equity levels of other central banks is difficult because of the following reasons:

The RBI’s public policy mandate and their impact on its balance sheet and risks 12. The RBI is a full service central bank. Among its varied functions, the role of monetary authority, forex reserve management and fostering of financial stability can particularly give rise to balance sheet and contingent risks for the RBI. The most significant impact of public policy considerations on the RBI’s balance sheet is the size of the forex reserves maintained to manage the volatility in the exchange rate. While these reserves provide the economy with a buffer against external stress, they give rise to significant risks for the RBI, as they have to be maintained as open, unhedged positions thereby exposing the RBI to currency risk on more than three-fourths of its balance sheet. In the past, mark-to-market (MTM) losses of 1.1 to 1.5 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP) have been experienced during certain periods. Moreover, the materialization of sterilization risks has caused large variability in RBI’s surplus during years of strong foreign inflows, when the balance sheet is already under strain due to the MTM losses. Nevertheless, the RBI has never suffered an overall loss in any year. RBI’s rationale for risk parameterization 13. As part of the review of the extant ECF, the Committee took into consideration the RBI’s rationale for risk parameterization: (i) The RBI had adopted the then prevailing Basel methodologies for market, credit and operational risks as these represented the most widely accepted risk assessment methodologies. At the time of adoption, the S-VaR represented the latest risk management standard as it was introduced globally in 2009 by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) in the aftermath of the GFC to address the limitations observed in the VaR methodology during the crisis. Other leading central banks were seen to be using this approach at that point of time. The actual risk parameterization of the ECF - return period, time horizon, size of data set, distribution assumptions, components of economic capital, etc. was carried out keeping in mind RBI-specific considerations. (ii) The 99.99 per cent CL was selected in recognition of the fact that the RBI is the external face (international counterparty) of the Government and also forms the primary bulwark during external crises for which it requires financial resilience to match the highest credit rating in international markets in light of the following:

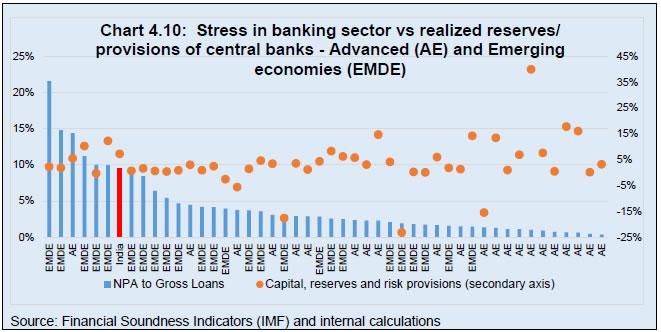

(iii) The objective of RBI having the financial resilience to match the highest credit rating in international markets was to be seen as an unimpeachable counterparty in international transactions and convey its ‘creditworthiness’ to the external sector, even during times of crises. (The importance of financial resilience can be seen as an important learning from the success of the FCNR (B) swap scheme during the Taper Tantrum of 2013); (iv) The financial stability risks are those rarest of the rare, fat tail risks whose likelihood can never be ruled out and whose impact can be potentially devastating. The ECF takes cognizance of the fact that emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) operations would be riskier in banking sectors with high non-performing asset (NPA) levels. The NPA crisis has thrown light on the challenges that arise if a sizable majority of the banking sector needs to be recapitalized during a financial stability crisis. This necessitates the need for RBI’s balance sheet to be demonstrably credible to discharge the LoLR function. The extant ECF-SSDP and risk provisioning 14. The Committee, thereafter, reviewed the trends in RBI’s surplus distribution under the ECF-SSDP framework from a historical perspective, as well as in comparison with other central banks. In this regard, the Committee noted the following:

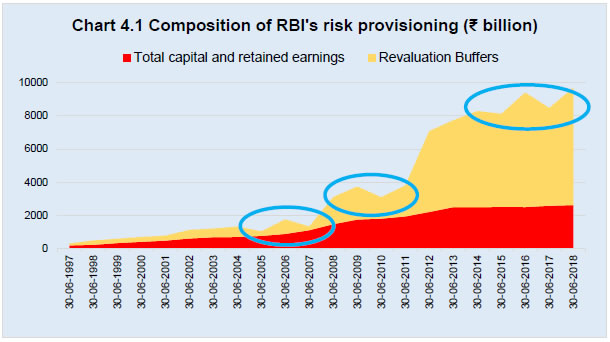

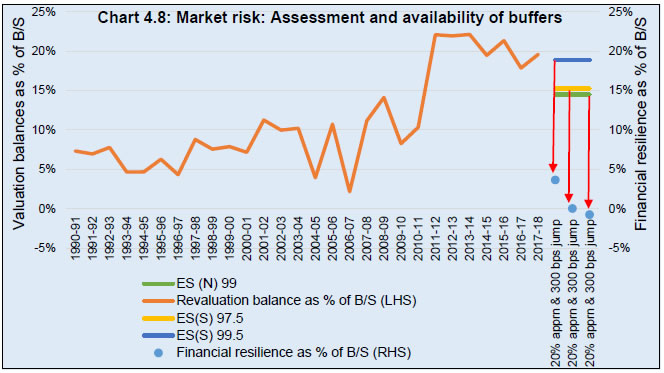

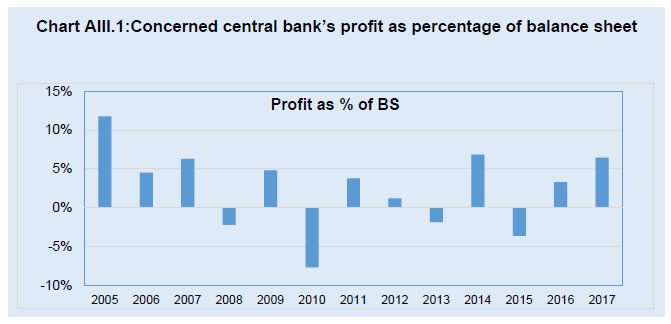

Quality of RBI’s risk buffers 15. Consequent to the transfer of surplus as indicated above, the RBI’s realized equity (Capital, Reserve Fund, Contingency Fund [CF] and Asset Development Fund [ADF]) as a proportion of balance sheet is at similar levels as in the late 1990s, though significant amount of unrealized revaluation balances are now available to act as risk buffers against market risks. 16. The RBI’s economic capital has also undergone a significant transformation over the past 20 years, with the unrealized revaluation balances now accounting for almost 73 per cent of the RBI’s economic capital in 2017-18 vis-à-vis 37.9 per cent in 1997. The Committee’s observations and recommendations 17. The Committee reviewed the extant ECF and its associated SSDP. The Committee has made the following observations/ recommendations. Economic capital levels 18. The Committee observed that even if the RBI’s economic capital could appear to be relatively higher, it is largely on account of the revaluation balances which are determined by exogenous factors such as market prices, and the RBI’s discharge of its public policy objectives. The proportion of realized equity to balance sheet has come down through the surplus distribution – balance-sheet expansion adjustment process since the adoption of Malegam Committee recommendations/ ECF as modified by SSDP. Review of status, need and justification of RBI’s buffers 19. The status, need and justification of various reserves, risk provisions and buffers maintained by the RBI were reviewed by the Committee, which recommended their continuance. The Committee recommended that the RBI should explicitly recognize the ADF not only as a provision for capital expenditure but also as a risk provision in case of need. Treatment of revaluation balances 20. The Committee recommended the inclusion of the revaluation balances as a part of RBI’s overall risk buffers, but with the recognition of its special character in view of their volatility, limited usability, significant strategic and operational constraints on their monetization. The principles of non-distribution of revaluation balances, mapping these only against market risks, and one-way fungibility vis-à-vis realized equity would need to be continued. Transparency in accounts 21. In view of the distinction sought to be made between realized equity and revaluation balances, the Committee recommended a more transparent presentation of the RBI’s Annual Accounts with regard to the components of economic capital (Table E.1). Articulation of financial resilience of the RBI 22. Going forward, the desired financial resilience for the RBI may be articulated by the Central Board in terms of the risk protection desired for its balance sheet. Selection of the risk model to be used 23. Given that ES is a better risk measure for tail risk as well as a coherent risk measure unlike VaR and S-VaR and that there is an increasing convergence on the use of ES, adoption of the ES methodology for the RBI’s market risk provisioning was recommended. Selection of risk parameters 24. Keeping in view, the historical incidence of stress and the need to maintain high level of financial resilience for RBI as well as to take into account the volatility and cyclicality in revaluation balances, the Committee considered various alternate risk parameterizations and selected the ES 99.5 per cent CL under stress conditions as the target resilience for market risk. The Committee noted that this was higher than other central banks who were seen to be using ES 99. The Committee also articulated a risk tolerance limit of ES 97.5 per cent CL based on historical analysis to impart the necessary flexibility to account for the cyclical volatility in RBI’s valuation buffers. Risk provisioning to cover shortfall in market risk would be triggered only if the tolerance limit of ES at 97.5 per cent CL is breached. 25. The Committee was also of the view that even when capital flows and the rupee are strong, government finances buoyant and the country prospering, the RBI will need to have adequate financial resilience to absorb the risks of the challenging monetary policy conditions which would arise in such a scenario caused by large inflows. Assessing off-balance sheet exposures 26. The RBI should assess the risk of its off-balance sheet exposures in view of their increasing significance. The country’s rainy-day savings 27. The Committee recognized that the RBI’s financial stability risk provisions need to be viewed for what they truly are, i.e., the country’s savings for a rainy day (a financial stability crisis), built up over decades, and maintained with the RBI in view of its role as the LoLR. Its balance sheet, therefore, has to be demonstrably credible to discharge this function with the requisite financial strength. Assessing financial stability risks 28. Globally, central banks are seen to be key custodians of financial stability. While they are known to use scenario analysis to assess risks arising from such actions, this is an area where most central banks, including the RBI, are relatively more discreet because of the associated moral hazard in spelling it out upfront. In India, the position of law is such that the RBI is not only the monetary authority, but also the regulator and supervisor, inter alia, of commercial banks, NBFCs and payment systems, and the debt manager of the Government. The Committee agreed that the RBI has one of the widest financial stability mandates deeply entrenched in the RBI’s statute and it is also bound by Section 47 of the RBI Act, 1934 to maintain the financial resources commensurate with the task. While the potentially destabilizing events have been skilfully handled through successful mergers, acquisitions and recapitalization in the past, the Committee acknowledged that the possibility of financial stability risks materializing can never be ruled out, especially in view of the lessons learnt from the GFC. 29. Given that the Government’s manoeuvrability on recapitalization of commercial banks or of the RBI could be constrained during a financial stability crisis, the Committee recognized the need for the RBI to maintain adequate risk buffers to ensure appropriate level of financial resilience in such circumstances. 30. The assessment made in the initial implementation stages of the extant ECF using peak liquidity scenario analysis had suggested that this risk buffer should be between 2 to 6.5 per cent of the RBI’s balance sheet. In light of the same, the Central Board had previously decided to maintain the buffer at 3 per cent with a medium-to-long term target of 4 per cent of the balance sheet. The Committee was also informed by a separate scenario analysis to assess the RBI’s ELA requirements using the European Central Bank’s (ECB) methodology for the liquidity stress-testing of commercial banks under its jurisdiction. Thereafter, a recovery rate ranging from 60 percent to 80 percent on the ELA was applied to estimate the RBI’s LoLR risks. The Committee considered the scenario of ELA to top 10 commercial banks with an 80 per cent recovery rate which results in a risk estimate of 4.6 per cent of the balance sheet. This analysis did not take into consideration the interconnectedness in the financial sector, the risks arising out of Indian banks’ overseas operations or the risks arising from the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC) which is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the RBI. In light of the above, the Committee recommended that the size of the financial and monetary stability risk provisions should be maintained at 4.5 to 5.5 per cent of the balance sheet. The scale of provisioning was moderate when assessed against the scale of costs of financial stability crises globally. Monetary stability risks 31. The CRB represents the cushion for both financial stability as well as monetary stability risks in view of their low correlation. Assessing credit and operational risks 32. The Committee recommended the adoption of the Basel III Standardised Approach for assessing credit risk of the forex portfolio (which also covers off-balance sheet exposures) and the new Standardised Approach for operational risk. Joint credit-market risk modelling 33. The RBI should consider joint credit-market risk modelling as this would help simulate the combined impact of a crisis and may lead to lower risk provisioning due to diversification. Size of realized equity 34. This should cover the requirements of the CRB (i.e., sum of credit risk, operational risk, and financial and monetary stability risks) as well as any shortfall in revaluation balances vis-à-vis the market RTL. Given that, as on June 30, 2018, there was no shortfall in revaluation balances, the size of the realized equity should be 6.5 per cent of the balance sheet, with a lower bound of 5.5 per cent. This represents 1.2 to 1.4 per cent of the GDP. 35. The net position of the risk provisions as determined by applying the recommendations of the Committee is summarized in Table E.2. Application of the Committee’s recommendations to the RBI’s balance sheet for the year 2017-18 results in excess revaluation balances of 0.7 per cent of balance sheet and excess realized equity ranging from 0.7 per cent at the upper bound of CRB to 1.7 per cent of balance sheet at the lower bound of CRB.

Treatment of excess realized equity 36. The excess realized equity as on June 30, 2018 ranges from ₹ 26,280 crores (at upper bound of CRB) to ₹ 62,456 crores (at lower bound of CRB). The excess realized equity as on June 30, 2019 will need to be determined on the basis of RBI’s finalized annual accounts for the financial year 2018-19 as well as the realized equity level decided upon by the RBI’s Central Board. Opportunity cost of RBI’s capital 37. The Committee was also of the view that the return/ cost of RBI’s capital, which is held for public policy objectives involves considerable positive externalities. If these do need to be assessed, it may be done on two broad principles viz. (i) the difference in the overall return on the assets held and the average debt servicing cost of the Government and (ii) the opportunity cost of capital which is the return that the Government would have generated had RBI’s capital been redeployed. With regard to overall return, the assets held against risks buffers could include both a portion of the Net Foreign Assets (NFA) and the Net Domestic Assets (NDA), depending on the composition of the RBI’s balance sheet at any given time. On NDA, RBI receives coupon interest on the G-sec it holds, which is predominantly returned to the Government in the form of surplus transfers. On NFA, the coupon returns may be lower than on NDA, but are typically augmented by valuation returns that accrue to the revaluation balances. The positive impact of NFA on the sovereign rating reduces Government’s overall borrowing costs, and hence has an indirect pecuniary benefit. 38. With regard to the opportunity cost of RBI’s capital and retained earnings, given that G-sec are held against it, the fiscal impact of RBI’s realized equity is minimal1 as RBI predominantly returns the coupon received on the G-sec. Further, given the large size of India’s GDP, the transfer of RBI’s ‘excess’ capital will not have a material impact on its debt-GDP ratio, while negatively impacting other rating criteria used by the CRAs. With regard to the possibility of the debt held against central bank’s capital crowding out the private sector borrowings, the Committee noted that Meyer (2000) had observed that government debt held by the private sector is not affected by the existence or the level of the surplus held by central banks. The opportunity cost of RBI’s capital is, thus, seen to be relatively small, even without taking into consideration the positive externalities of monetary and financial stability which these buffers facilitate. The Surplus Distribution Policy going forward 39. The surplus distribution policy (SDP) should move away from targeting total economic capital alone (as under the extant SSDP), to one where it has a dual set of targets:

40. Given that market risk was mapped against revaluation balances and only a shortfall in these balances needs to be provided for, the SDP, in effect, will be required to target the required level of realized equity (‘requirement’) for covering:

41. The ‘available realized equity’ (ARE), i.e., Capital, Reserve Fund, CF and ADF, will be compared with the ‘requirement’ to determine surplus distribution on the following lines:

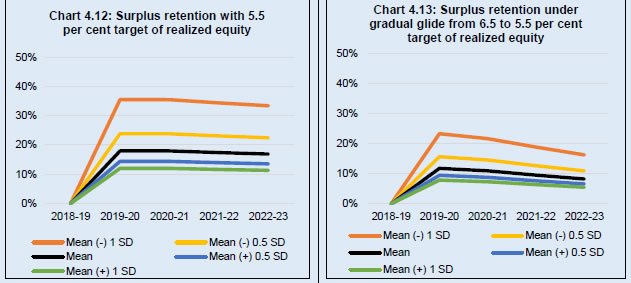

Consistency in the level of risk provisioning 42. The Committee noted that on making reasonable allowance for volatility (± 0.5 SD and ± 1 SD) in the RBI’s net income relative to its balance sheet size, average risk provisioning over the five year period of 2018-19 to 2022-23 for CRB of 5.5 and 6.5 per cent could range from 8.1 to 16.6 per cent of net income in the normal scenario with a range of 5.4 to 11.1 per cent of net income in case of a positive shock and 16.0 to 32.8 per cent of net income in case of a negative shock respectively. The Committee also noted that these were illustrative and not exhaustive scenarios. Treatment of excess revaluation balances 43. The Committee was of the view that it should not concern itself with the issue of alternative deployment of excess accumulated revaluation balances as it did not fall within the Committee’s ToRs. The Committee recommended that these may continue to remain on the balance sheet till such time that they may be realized through the sale or maturity of the underlying asset. Interim dividend and aligning RBI’s financial year with the Government’s fiscal year 44. The Committee recommended that the RBI accounting year (July to June) may be brought in sync with the fiscal year (April to March) from the financial year 2020-21 for the following reasons:

Periodicity of review 45. The Committee recommended that the framework may be periodically reviewed every five years. Nevertheless, if there is a significant change in the RBI’s risks and operating environment, an intermediate review may be considered. 1 An Overview of the Role and Relevance of Central Banks’ Financial Resilience 1.1 The RBI is one of the pioneers in the area of central bank capital, starting with the Subrahmanyam Internal Working Group which submitted its report in early 1997. This preceded the publication of Dr. Peter Stella’s seminal paper ‘Do Central Banks Need Capital’ (Stella, 1997), which subsequently triggered considerable research in this area. This was also before the creation of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) in 1998 – a framework which explicitly laid emphasis on the financial resilience of its member central banks as a means of ensuring their functional independence. 1.2 The Subrahmanyam Group was followed by the Usha Thorat Committee in 2004 (recommendations of which were not accepted), the Malegam Committee in 2014 (recommendations of which were accepted) and the ECF which was developed during 2014-15 and operationalized by the RBI in 2015-16, so as to operate concurrently with the Malegam Committee’s recommendations which were valid for a three-year period, i.e., 2013-14 to 2015-16. 1.3 Given that the role and adequacy of central bank capital is an issue which generally receives greater attention only during crises, the continued attention on this issue in India reveals the importance that the Government and the RBI have placed on finding the right balance between the opportunity cost of central bank capital vis-à-vis the socio-economic cost and the negative externalities of having an undercapitalized central bank, making it imperative that a holistic and comprehensive perspective be taken based on what is in the best interests of the country as a whole. The challenge in finding this right balance arises primarily from the fact that the opportunity cost of central bank capital is relatively easier to measure than the benefits of having a well-capitalized central bank for fostering ‘monetary and financial stability’, given that these are a public good and, therefore, difficult to measure during normal times. I. Central bank capital and its role in monetary and financial stability 1.4 Central banks do not require capital to carry on operations, as being the managers of domestic liquidity they can do so simply by printing currency/creating liquidity. However, central banks require financial resilience2 to absorb the risks that arise from their operations and delivery of their public policy mandate.3 To fully appreciate the importance of the same, one needs to view central banks as macro-level risk managers, mandated with the public policy objective of buffering the economy from monetary shocks and financial stability headwinds (by virtue of they being the monetary authority as well as the LoLR). Emerging market central banks have an additional role of managing external stability in the face of volatile capital flows and the spillover effect of monetary policy changes by AE central banks. The role of central banks’ financial resilience is to enable these institutions to focus on their primary function of fostering monetary, financial and external stability, even in the midst of crisis, without being diverted by balance sheet concerns. This is particularly important given that central bank capital generally represents public resources and the central bank’s management can be held accountable for its losses. 1.5 There are varied views on the role of central banks’ capital/financial resilience. On the issue of central banks being able to carry on operations even with negative capital, Stella and Lönnberg (2008) drew a distinction between ‘technical insolvency’ and ‘policy insolvency’, i.e., a central bank may be able to carry on day-to-day operations with negative equity but may not be effective in the implementation of its policy objectives. Adler, Castro, and Tovar (2016), Klüh and Stella (2008), and Perera, Ralston, and Wickramanayake (2013) had observed a negative relationship between central banks with weak financial resilience and the discharge of their policy mandate. Dalton and Dziobek (2005) concluded that failure to address ongoing losses, or any ensuing negative net worth, will interfere with monetary management and may jeopardize the central bank’s independence and credibility. Sims (2013) also concluded that the LoLR role of the central bank may not be credible if the central bank equity position is not strong. 1.6 Bindseil, Manzanares, and Weller (2004) found that as a fully automated and credible rule of recapitalization of the central bank by the government is difficult to implement in practice, positive capital4 seems to remain a key tool in ensuring that independent central bankers always concentrate on price stability in their monetary policy decisions. Archer and Moser-Böehm (2013) observed that the mere act of seeking recapitalization from the government might cause central banks to give up an authority that had been purposefully delegated to them. 1.7 Specifically, Friedman and Schwartz (1963) observed that the US FED’s concern about its own balance sheet weighed on the decision which prevented an aggressive monetary expansionary response to the emerging Great Depression. Krugman (1998) and Cargill (2005) have argued that Bank of Japan (BoJ) committed similar policy errors as it was concerned with its net worth position. Amador et al. (2016) observed that the dilemma between the desire to maintain currency pegs and the concern about future losses can lead the central bank to first accumulate a large amount of reserves, and then to abandon the peg, as observed in the Swiss case. Hall and Reis (2015) arrived at a similar conclusion. 1.8 On the other hand, according to Subramanian et al. (2018), central banks can always deliver on their domestic operations regardless of their net worth because they can always issue liabilities (‘print money’); and that central banks are a part of the government, hence it is the broader government balance sheet that matters, not that of any of its constituents. In this regard, Buiter (2008), states that a central bank’s balance sheet is uninformative about the financial resources it has at its disposal and about its ability to act as an effective LoLR and MMLR, and, therefore, the equitable insolvency (the failure to pay obligations as they fall due) is more relevant for central banks than balance sheet insolvency, i.e., liabilities exceeding assets. He, however, noted that the scale of recourse to seigniorage to safeguard central bank solvency may undermine price stability. Benecka et al. (2012) did not find any significant link between central bank financial strength and inflation. Frait (2005) as well as Dalton and Dziobek (2005) sought to differentiate between central banks with operating losses from those with valuation losses caused by currency appreciation. Ernhagen, Vesterlund, Viotti (2002) broadly agreed that as long as overall conditions are reasonable, the ‘seigniorage’ income of a central bank will add to the financial strength of the central bank. A central bank would be able to ensure its solvency through seigniorage as long as it does not have significant foreign exchange-denominated liabilities or index-linked liabilities. For these reasons, a number of central banks such as those of Israel, Chile, the Czech Republic and Mexico have continued to operate quite successfully for long periods with negative capital. Restrepo et al (2008), on the other hand, in relation to the Chilean case, observed that it would take at least 25 years for its net worth to reach positive levels, with a high chance of it being negative equity even after 25 years. 1.9 In this regard, an EMDE central bank which is one of the most cited examples of an effective central bank despite having negative equity over a prolonged period, cited the following reasons for central banks to maintain sufficient capital in its 2006 annual report, while mentioning that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has for several years recommended its recapitalization and that risk-rating agencies mention the central bank’s negative capital as something that should be corrected:

1.10 The Committee noted that the aforementioned central bank continues to operate with negative equity as a recapitalization programme launched in 2006 could not be completed in 2009 due to a worsening of the government’s fiscal position. 1.11 With regard to RBI specifically, Subramanian et al. (2018), using the approaches of ‘modal’ risk parameterization and regression analysis, concluded that it is overcapitalized by 13 to 22 percentage points. Similar conclusions were drawn in the Economic Survey 2016–17 and Economic Survey 2017–18. Lahiri et al. (2018), on the other hand, concluded that the RBI was undercapitalized by 5 per cent compared to the average of emerging economies. III. Central banks’ unique risk environment and their risk management frameworks 1.12 Even though central banks are exposed to some similar risks as commercial banks, i.e., policy and strategic risk, market risk, credit risk, liquidity risk (at least, on forex reserves), information security risk, operational risk, reputation risk, etc., their operating environments are rather unique, resulting in a need for adopting risk management frameworks which are specifically adapted to their environment and public policy mandate: (i) Being public policy institutions, the focus of central banks is on ensuring efficacy of their policy actions even if such actions entail assuming significant balance sheet risks—an approach which is referred to within the RBI as the Principle of Public Policy Predominance (PPPP). (ii) This principle impacts the central bank balance sheet and its management significantly. For instance, common risk management tools such as hedging may not be available to central banks and risk-return considerations will figure low in priority in important decisions such as balance sheet composition (the size of forex reserves being more of a strategic decision), keeping the forex reserves as an open position (as they need to be available for intervention purposes), the absence of duration management for the domestic securities portfolio (as it could impact monetary policy operations), etc. (iii) Some of the largest risks, i.e., monetary and financial stability risks, are specific to central banks and they have been seen to materialize at scales which account for a significant portion of an economy’s GDP. If these risks do indeed materialize and lead to a situation where central banks need recapitalization support, the ability to conduct monetary policy may get eroded, thereby constraining their independence. Moreover, given their scale of operations, central banks are difficult to recapitalize as evidenced by several central banks which operate with negative capital. (iv) Given their public policy objectives, central banks may also be required to adopt a ‘counter-intuitive’ approach to risks during crises, wherein they relax their RTL and collateral standards to act as LoLR as well as MMLR, precisely at the time when commercial entities are strengthening their risk management standards. (v) On the other hand, there are certain inherent strengths in a central bank’s balance sheet which are:

1.13 Given that roles and responsibilities of central banks vary considerably, as do the environments they operate in, their financial relationship with the Sovereign (RTMs and surplus distribution policies) and their accounting frameworks, there is no internationally laid down risk capital framework for central banks. Central banks, therefore, develop and adapt risk management frameworks to their own specific conditions and requirements. This also means that international comparisons will only reveal international trends and averages but not a generally agreed international norm. Nevertheless, the broad approach that most central banks have followed for developing their risk frameworks is along the following lines:

1.14 In the following chapter, international practices adopted by central banks with regard to risk management as well as economic capital and financial resilience are examined. 2 Review of Central Banking Practices 2.1 ‘Economic capital is defined as the methods or practices that allow banks to consistently assess risk and attribute capital to cover the economic effects of risk-taking activities’ (Bank for International Settlements [BIS], 2009). Prior to the development of its own ECF, the RBI conducted a cross-country survey of the frameworks used by 36 leading advanced and emerging economy central banks. The purpose of this exercise was to evaluate the frameworks used by other central banks to assess their own risk capital and provisioning requirements. This was further supplemented by technical workshops held with the BIS and the ECB as well as detailed discussions with Banco Central do Brasil (BCdB), Bank of England (BoE), BNM, Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ), South African Reserve Bank (SARB), and Sveriges Riksbank amongst others. More recently, the Government has also conducted a survey of 51 central banks with regard to their total equity levels and risk models used. The Committee was informed by the findings of both these surveys, as well as an extended analysis of 53 central banks (covering all the central banks by the Government and the RBI) on their economic capital, realized equity and other sources of financial resilience and their relative position with regard to macroeconomic and financial stability indicators. I. Various approaches towards strengthening the central banks’ financial resilience 2.2 Archer and Moser-Böehm (2013) identified capital targets, accounting policies, risk-sharing arrangements, profit distribution and recapitalization mechanisms as key determinants of central bank financial strength. Interestingly, following the GFC, a number of leading central banks strengthened their financial resilience by adopting at least one of these measures as brought out in Box 2.1.

2.3 Accordingly, the survey sought to identify key central banking practices in this regard, which are discussed below: (i) Capital Structure: The amount of central bank capital is generally stipulated by their respective statutes, while reserves/ risk provisions are seen to be the dynamic components of a central bank’s capital structure, changing over time and circumstances. It was observed that several leading central banks, e.g. BoE, ECB, RBA and RBNZ, have adopted holistic risk capital frameworks to assess the adequacy of their reserves and provisions. The RBI’s ECF is, thus, in line with current central banking practices. The salient features of BoE, ECB, RBA and RBNZ’s capital frameworks are presented in Annex III. Other than these, there are a number of other central banks which use targeted levels of reserves/ risk provisions such as the Banque de France (BdF), BoJ, US FED, Norges Bank and the SNB, amongst others. The targeted levels of reserves/ risk provisions of these central banks are also given in Annex III. (ii) Evolution of risk methodologies: The survey also brings out the fact that central banks are increasingly adopting a model-based approach for assessing risks and that these risk methodologies evolve with the operating environment and the developments in risk assessment. Table 2.1 shows that a number of central banks had started adopting VaR for risk management/capital purposes well before the GFC. However, the crisis revealed severe shortcomings of the VaR (Crotty, 2007; Gopalkrishna, 2013) and central banks strengthened their risk frameworks with the BoE9, RBNZ and the RBI adopting the S-VaR methodology which was prescribed by the BCBS to replace VaR for commercial banks in 2009. 10 A number of other central banks started moving to ES, which has been prescribed by the BCBS to replace S-VaR in 2016. While the risk parameters range from VaR 95 per cent (Hong Kong), S-VaR 99.9 per cent (New Zealand), S-VaR 99.99 per cent (India) to ES 99 per cent (ECB), etc., ES 99 per cent appears to be emerging as the risk parameter of choice among several central banks presently.

(iii) Risk transfer mechanisms: Certain central banks (including the RBI which has the MSS) supplement their financial resilience with RTMs with the government which are detailed in Annex IV. These RTMs include setting up of Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) where the risk return of quasi-fiscal actions are transferred directly to the government; the direct transfer of losses exceeding the available reserves to the government; making accounting changes whereby central bank losses are treated as a future claim on the government; and ad hoc measures such as issue of bonds by the governments to the central banks to cover their losses. (iv) Efficacy of RTMs: The efficacy of RTMs can truly be assessed only during an actual crisis when the fiscal space available to the government could also get significantly reduced. Post-GFC developments have shown that sovereign debt crises can be quickly triggered when large-scale public sector actions are initiated. There are other specific instances where RTMs have been less effective than initially expected. During the Asian Crisis, an East Asian government issued inflation-indexed government bonds (amounting to around 16 per cent of GDP) to its central bank in exchange for the latter’s claims on banks arising due to the liquidity assistance extended by it. However, the bonds were restructured in tranches prior to any payment being made thereon by the government so as to yield 0.1/1.0 per cent with no fixed repayment date/ 20 years maturity. Incidentally, the stipulation that a charge be paid by the government to the central bank should the central bank’s ratio of capital to monetary obligations fall below 3 per cent was abolished in 2011. There have been other instances where recapitalization of central banks has been done through non-interest bearing bonds. In view of the same, the preference of a central bank could normally be to expect ex ante capitalization. Even in the case of a Asian central bank, which has statutory provision for automatic (ex post) recapitalization, surplus ranging from 41 per cent to 59 per cent was transferred (ex ante) to the risk reserves during 2008–2010, which was higher than the required level of 10 per cent. This requirement has since been raised to 30 per cent. The recent introduction of the capital framework in an AE central bank also points towards the merits of ex ante capitalization, even though the SPV route provides it with one of the strongest RTMs (whereby certain significant central banks’ risks do not enter into the central bank’s books). (v) Treatment of revaluation balances: The cross-country survey suggests that while a few central banks do not recognize valuation gains on their balance sheets or in the profit and loss (P&L), most central banks treat the revaluation balances either as ‘limited-use risk provisions’ or as ‘risk capital’. The spectrum of the varied approaches is outlined below.

(vi) Credit ratings of central banks: The survey revealed that a number of central banks had been rated by CRAs in the past, with many of these ratings having been unsolicited, though in certain cases such as the SNB, the rating was obtained in view of issuance of foreign currency denominated debt. Nevertheless, it was observed that the credit ratings of central banks which were not a part of any currency union were predominantly at the same level as their respective sovereigns. Rating methodology of the various CRAs (S&P, Moody’s and Dominion Bond Rating Service [DBRS]) are given in Annex VI. In this regard, the Sovereign rating methodology of S&P was updated in December 2017 to cover both the Sovereign government and monetary authorities. (The monetary authorities were till such time addressed by a separate ‘monetary authorities rating methodology’.) (vii) Central bank operations and Sovereign ratings: It was noted that CRAs in their assessment of sovereign ratings assign weightage to areas which generally fall within the purview of central banking operations. For instance, the S&P’s sovereign credit analysis rests on five pillars of institutional assessment, economic assessment, external assessment, fiscal assessment and monetary assessment. Of these, monetary assessment depends on exchange rate policy and monetary policy. While the criteria for exchange rate assessment is whether the country has a reserve currency and its exchange rate regime; the criteria for monetary policy assessment were the following:

Source: Sovereign Rating Methodology by S&P global ratings (Dec 18, 2017), https://www.spratings.com/documents/20184/4432051/Sovereign+Rating+Methodology/5f8c852c-108d-46d2-add1-4c20c3304725 2.4 There was a view that as none of the rating parameters covers the level of economic capital held by a central bank, rating of a central bank, based on the economic capital is a misnomer. The alternative view was that global experience, as brought out in survey of literature, showed that financial resilience of a central bank was an important facilitator for achieving quite a few of the above rating criteria. The Committee noted both views. II. Central banks’ economic capital levels as defined under the ECF 2.5 Given that one of the main points supporting the perspective that the RBI is overcapitalized is a cross-country survey based on median as the ‘measure of central tendency’ published in the Economic Survey 2016 and 2017, the Committee considered the same. 2.6 For this purpose, central banks’ economic capital, as defined under the RBI’s ECF (i.e., capital, reserves, risk provisions and revaluation balances), were assessed for all the surveyed central banks. This number does not necessarily reflect what the central banks themselves consider their own economic capital to be.12 In this regard, the RBI has an overall fifth rank at 26.8 per cent of its balance sheet in 2018 with respect to central banking economic capital, which largely emanates from revaluation balances accumulated by rupee weakness vis-à-vis the US dollar. Incidentally, RBI’s position has moderated from 2013 when it had the second highest economic capital level. Among the EMDEs, the RBI’s position is fourth. The average and median among the surveyed countries on this metric when revised for incorporating latest information as well correction of discrepancies are 8.4 per cent and 8.0 per cent respectively. The relatively high level of economic capital in the case of all the above four EMDEs is primarily on account of their substantial revaluation balances arising from currency depreciation on their forex reserves. The relatively high economic capital thus does not necessarily represent a source of strength, but rather is the imprint of previous episodes of external stress. 2.7 The Committee also reviewed the position of the central bank’s realized equity as this is the component which is actually determined by the central bank management (revaluation balances being determined in a largely autonomous manner by market price movements). The RBI’s realized equity was observed to be 7.2 per cent of the balance sheet in 2018 as revaluation balances account for 73 per cent of RBI’s economic capital. 2.8 The Committee, however, noted that drawing definitive conclusions from such comparative analysis would be difficult for the following reasons:

2.9 The Committee noted the varied central banking practices arising due to, inter alia, the differences in their mandates, accounting frameworks, balance sheet structures and operating environments. The Committee, thereafter, reviewed the RBI-specific environment. 3 The RBI’s Public Policy Mandate, the Impact on its Balance Sheet and its Risks 3.1 Having reviewed international practices, the Committee deliberated on the RBI’s specific environment, keeping in consideration the statutory mandate under Section 47 of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 and public policy mandate of the RBI, including financial stability considerations. The functions of the RBI, its public policy mandate and their implications on the balance sheet and the attendant risks are discussed ahead. The RBI’s management of its risk, its risk provisioning under the ECF and the distribution of surplus under Section 47 of the RBI Act, 1934 are covered in Chapter 4. 3.2 The RBI is a full service central bank and its varied functions are briefly outlined below:

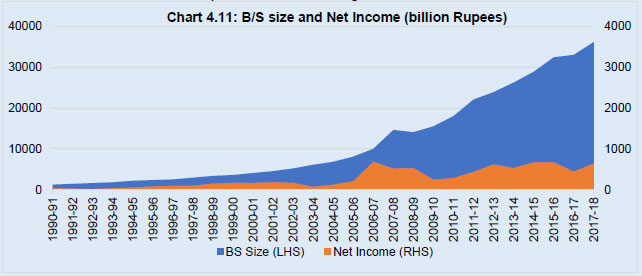

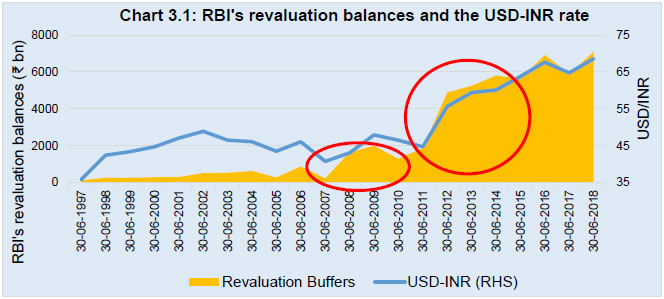

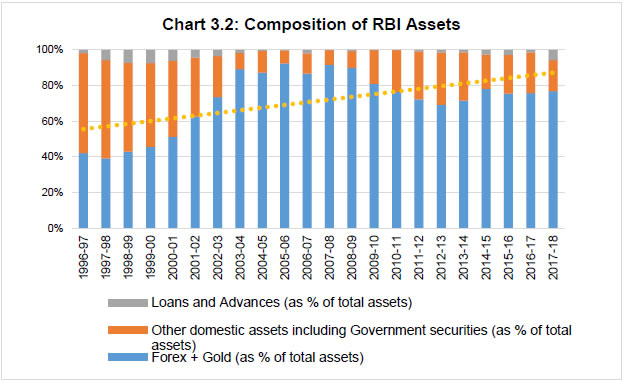

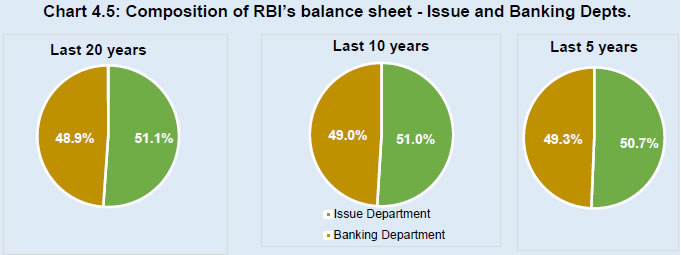

II. Impact of the RBI’s functions and public policy objectives on its balance sheet A broad overview of the RBI’s balance sheet dynamics 3.3 The size and composition of the RBI’s balance sheet is determined largely by the prevailing economic conditions, the external sector, its policy objectives and policy stance. To bring these inter-linkages, the balance sheet is presented in stylized form in Table 3.1. Liabilities 3.4 Being the provider of domestic liquidity, the RBI’s liabilities largely consist of reserve money (typically accounting for about 70 per cent of total liabilities) and its net non-monetary liabilities (which largely represent the RBI’s economic capital). Assets 3.5 On the asset side, the RBI’s balance sheet comprises mainly all its NFA representing, largely, the forex and gold reserves, and its NDA comprising mainly government securities. The share of NFA has varied between 65 and 90 per cent of total assets over the last 10 years. In June 2018, the share was about 77 per cent. The size, acquisition and sale of foreign assets are independent of considerations related to the balance sheet. Increases take place when the overall BoP is in surplus, either through current account surpluses or through capital account surpluses, or both; but in our context BoP surplus mostly emanates from surplus on the capital account. The foreign exchange reserves decrease sharply in years of substantial deficit on the capital account, e.g., in 2008–09. 3.6 The NFA are held in the interest of maintaining external and domestic financial and economic stability of the country. The composition of these forex reserves is determined in consultation with the Government; the reserves are spread over a basket of currencies to incorporate benefits of diversification, and the weights of currencies and the maturity of assets reflect the RBI’s long-term risk and return preferences, while ensuring their safety and liquidity. (Even here, the risk-return preferences have to take into consideration factors such as the need to maintain a major portion of reserves in the intervention currency, etc.) 3.7 The magnitude of NDA on the RBI’s balance sheet depends on the behaviour of the NFA. While accretion to the NFA results in the reserve money growth being met by such accretion, the RBI has to inject liquidity in the economy through OMO purchases in years of low growth in NFA, thereby increasing the magnitude of NDA. Overall trends in balance sheet size and growth 3.8 The size of the RBI’s balance sheet has been around 20 per cent of the country’s nominal GDP on a relatively stable basis, with a slight downward trend over the last decade or so. It is reasonable to assume that growth in reserve money (M0) which constitutes 70 per cent of the RBI’s balance sheet will approximate growth in nominal GDP in the foreseeable future. The RBI calibrates monetary expansion on the basis of income elasticity of broad money (M3) which used to range between 1.3 and 1.4 until 2010. This, however, has reduced to about 1 over the last five to ten years. The reduction in this elasticity is consistent with the significant reduction in financial savings of households observed over this period. However, reserve money growth may witness acceleration if financial savings start increasing again. 3.9 However, while the reserve money increases by nominal GDP growth rate, the movement in Net Non-Monetary Liabilities is predominantly on account of revaluation changes in the assets of the RBI whose growth or fall depends on the changing magnitude of the NFA, exchange rate and gold price movements, interest rate movements and other developments in international financial markets and the risk provisioning by the RBI. Impact of the RBI’s functions on its balance sheet Monetary policy 3.10 The primary objective of monetary policy is to maintain price stability while keeping in mind the objective of growth. With the RBI adopting the Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT) framework since 2015, the target level of inflation is sought to be achieved by influencing the level of interest rates in the economy. The objective of monetary policy operations is to enable the smooth transmission of monetary policy impulses to the financial system by ensuring that primary liquidity is consistent with the demand in the economy, such that the resulting interest rates can enable the RBI to achieve the objective of price stability, while being cognizant of growth concerns. In assessing primary liquidity (reserve money) requirements, the RBI has to meet the demand for currency from the public and liquidity needs of banks for statutory reserves. The size and growth of the RBI’s balance sheet is thus determined primarily by liability size considerations, i.e., reserve money. The balance sheet has had an annual growth of around 9.5 per cent over the past 10 years, and about 8.6 per cent in the past five-year period 2013-14 to 2017-18. The last five years’ average was low because of demonetization carried out in 2016–17. The impact of the monetary policy operations is on the following lines: Liquidity Adjustment Facility and Open Market Operations

Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) and Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR)

Exchange rate management 3.11 While operationally the exchange rate is determined by the market, i.e., forces of demand and supply, and the level of reserves is essentially a result of sale and purchase transactions, the level also needs to be seen in the overall context of exchange rate management. The conduct of exchange rate policy is guided by the objective of modulating undue volatility and discouraging speculative activities in the foreign exchange market, while ensuring that exchange rate movements are orderly and calibrated. In this regard, the RBI interventions are not governed by a predetermined target or band around the exchange rate. To illustrate this, we look at the BoP relationship which lists all transactions made between entities in a country and the rest of the world over a defined period of time which is reflected as:

3.12 Out of the three components of the BoP, capital flows by nature tend to be the most dominant factor in influencing the exchange rates in the short term, as capital flows tend to be larger and more volatile than the current account flows. The impact of capital inflows on the balance sheet is along the following lines:

Issuer of currency 3.13 The banking system would have to fund cash flows as currency is a leakage from the banking system to the extent it is held by the public as a direct claim on the central bank.

Maintenance of financial stability 3.14 The LoLR role of the RBI can potentially have a significant impact on its balance sheet size and composition. The primary risk arising from ELA operations would be on credit exposures to distressed entities. In addition to the credit losses, the ELA operations shall have an expansionary impact on the balance sheet and would be expected to increase the share of NDA in RBI’s total assets, not only on account of the increase in the RBI’s ‘loans and advances’ portfolio but also a decrease in forex reserves in dollar terms which could be expected in view of capital flight during financial stability crises. A depreciating rupee would make the reduction in forex reserves appear to be smaller in rupee terms. These scenarios have been captured under the ECF as brought out in Annex VIII. Banking regulator and supervisor of banks, non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) and primary dealers 3.15 This function is not expected to impact the RBI’s balance sheet directly. Nevertheless, even with an effective regulatory and supervisory framework, black swan events cannot be truly eliminated giving rise to ELA risks. Debt manager of both central and state governments 3.16 With the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, 2003 (FRBM Act) precluding the RBI’s operations from the primary market for government securities, this function does not significantly impact the RBI’s balance sheet. Nevertheless, it does give rise to significant operational risk. Operating the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation 3.17 As per Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation Act, 1961 the amount outstanding advanced by the RBI to the DICGC at any one time shall not exceed ₹5 crore rupees. Therefore, in normal times, DICGC operations will not have a significant impact on RBI’s balance sheet. However, in times of crisis, significant ELA to the DICGC cannot be ruled out. Further, the DICGC being a wholly owned subsidiary, significant losses beyond its capital could be expected to be borne by the RBI. Development role refinance to National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), National Housing Bank (NHB), Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI), India Infrastructure Finance Company Limited (IIFCL) 3.18 The RBI’s development role is not expected to have any significant impact on its balance sheet. The refinance support to these entities has been discontinued since a long time. 3.19 Having discussed the impact of the RBI’s functions on its balance sheet and contingent liabilities, the Committee, thereafter, reviewed the risks to which the RBI is exposed to. Currency risk 3.20 The most significant impact of public policy considerations on the RBI’s balance sheet is the size of the forex reserves maintained to manage the volatility in the exchange rate. While these reserves provide the economy with a buffer against external stress (a public good), they give rise to significant risks for the RBI. Given that these reserves represent a ‘war chest’, they have to be maintained as open, unhedged positions14 thereby exposing the RBI to currency risk15 on more than three-fourths of its balance sheet. Consequently, the RBI suffers losses when the rupee appreciates against the USD and/ or the other currencies in its forex portfolio and it gains when the rupee depreciates against them. Thus, counter-intuitively, the RBI suffers valuation losses during times when the economy is witnessing strong growth and large capital inflows which normally are associated with rupee appreciation.16 Table 3.2 brings out the large episodes of rupee appreciation in three distinct but relatively recent time periods. 3.21 Conversely, the RBI witnesses considerable accretion to its revaluation balances (i.e., Currency and Gold Revaluation Account [CGRA]) during periods of external stress (i.e., 2008, 2011 and 2013) when the trend towards depreciation is markedly strong. This is brought out in Chart 3.1.  3.22 The currency risks on the balance sheet also increases if the share of forex reserves increases as a percentage of the balance sheet. Chart 3.2 shows the changing composition of the RBI’s balance sheet with the share of forex reserves peaking in the mid 2000s due to strong capital inflows. Thereafter, there has been a fall in the share of forex reserves due to interventions during 2008, 2011 and 2013. There has been a marginal rise since then.  3.23 The Committee noted that given the expanding net negative International Investment Position (IIP) of India, the magnitude of foreign exchange reserves provides confidence in international financial markets. At present, the foreign exchange reserves (more than $400 billion) are significantly lower than the country’s total external liabilities ($1 trillion) and even lower than total external debt ($500 billion). This position is in contrast to that in 2008 when India’s foreign exchange reserves, at $310 billion, exceeded the then total external debt of about US$224 billion and provided a much larger coverage of total external liabilities that amounted to about $426 billion. This needs to be taken into account in assessing the external risk being faced by the country and the possibility that the RBI may be required to increase the size of its forex reserves with its concomitant implications for the balance sheet, risks and desired economic capital. This is especially important given that the RBI’s public policy objectives of maintaining external stability during a crisis would have to be pursued irrespective of the adequacy of its risk buffers. It is, therefore, imperative that the RBI maintains a forward-looking view on the adequacy of its risk buffers even during normal times. The Committee also noted that the RBI, in consultation with the Government, periodically reviews the adequacy of the country’s forex reserves. Further, a separate internal group of the RBI is looking into the question of developing a formal framework to assess the adequacy of the forex reserves. 3.24 The Committee also deliberated on the issue of whether as the central bank, the RBI has potentially an infinite capacity to prevent rupee appreciation as it can print money to purchase foreign currency. It noted that the RBI’s interventions are carried out in line with its exchange rate policy and not to prevent losses, which would go against its public policy mandate. Further, while the RBI has significant (not infinite) ability to intervene in the market, its capability to prevent its own losses during periods of rupee appreciation was not so. It was noted that sterilization operations in 2003–04 and 2009–10 following its intervention operations caused a significant decline in its gross income. Gold Price risk 3.25 The gold reserves are seen as strategic assets and not actively managed. The gold price risk, therefore, is fully provisioned for. This risk resulted in a valuation loss of (-) ₹16,370 crore in 2012–13 due to decrease in gold price. There is no interest rate risk for this asset. Interest rate risks 3.26 In addition to currency risks, the RBI has significant interest rate risks on both its forex as well as its domestic securities portfolio. While the RBI does actively manage the interest rate risk on its forex portfolio, this is not possible in the case of the domestic portfolio as such operations could conflict with monetary policy operations. These risks (including residual forex interest rate risks), therefore, need to be covered by RBI’s risk provisioning. The impact of simultaneous materialization of currency and interest rate risks 3.27 It was also observed that there have been occasions when increasing yields and appreciating rupee have materialized concurrently as indicated in Chart 3.3, resulting in considerable erosion of the RBI’s risk provisioning as seen from Table 3.3. For instance, in 2006–07, 75 per cent of RBI’s revaluation balances were wiped out amounting to 1.5 per cent of the GDP. In 2016–17, RBI’s revaluation balances fell more than ₹1 trillion due to an appreciating rupee and cross-currency movements. The only reason the markets, government fiscal balance and the economy as a whole are not impacted was that the RBI had sufficient risk provisioning to absorb these risks.  Do valuation risks matter or are they paper risks as they are essentially book entries? Do they require risk provisioning? 3.28 The answer is relatively straightforward: valuation risks are very real and can trigger substantial losses for the central bank. Undoubtedly, there is greater flexibility in their handling, given that they can be offset against previously accumulated valuation gains (in addition to previously accumulated realized surplus) and the concerned revaluation balances can operate in the negative through the year—till the balance sheet date (as has happened for the RBI in the case of IRA-FS in 2016–17 and 2017–18). On balance sheet date, all losses, whether they are valuation losses, credit losses, operational losses or ELA losses, have to be recognized. 3.29 In this connection, it was noted that a number of central banks have negative capital today, precisely because of their valuation losses. Credit risk 3.30 The credit risk of the RBI is generally believed to be low on account of the following reasons:

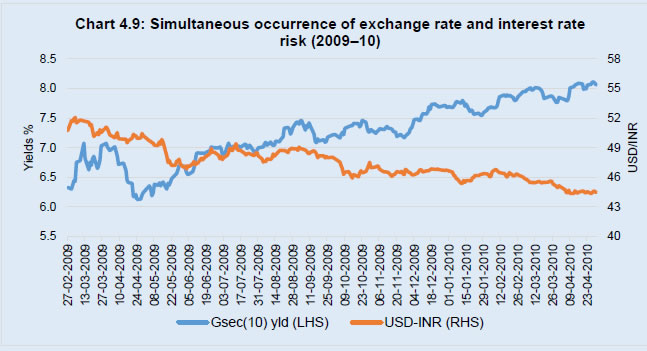

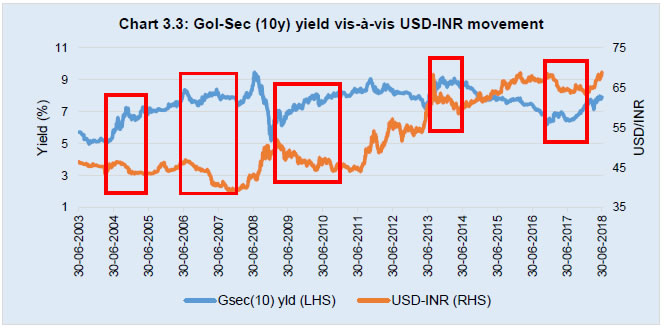

3.31 The RBI's forex reserves are invested in bonds/ treasury bills that represent debt obligations of highly rated sovereigns, central banks and supranational entities. Further, deposits are placed with central banks, the BIS and overseas branches of commercial banks. Nevertheless, the measurement, monitoring and management of credit risk by a central bank is important to restrict counterparty credit risk and to ensure that the overall level of portfolio credit risk is consistent with the risk appetite of the central bank. Further, it was also recognized that complete elimination of any form of risk may not be possible (or even considered desirable from the risk-return perspective) as risks can metamorphize into unexpected forms, in unanticipated areas. The same principle applies for credit risk as well. An expanding forex portfolio, a conservative investible universe and the need for maintaining reserves in high quality and liquid assets places limitations on the possibility of diversification. This has resulted in the rising concentration of risks, with the Hirschman–Herfindahl Index (HHI) of the portfolio approximated to be 47 per cent (the HHI indicates the diversification benefits are more pronounced when the HHI has a value below 20 per cent). Further, risk also emerges from the swap facilities entered into with some of the central banks as well as the off-balance transactions entered into with domestic counterparties. Risk provisioning is required for the residual credit risk from the forex portfolio. 3.32 With regard to domestic lending operations, as indicated above, there is little credit risk as RBI’s lending operations under normal conditions are collateralized with haircuts being maintained. However, significant credit risk can arise from ELA operations during periods of stress, which is captured separately under financial stability risks. Operational risks 3.33 Substantial operational risks emanate from the conduct of various operations of the RBI, particularly those outlined below:

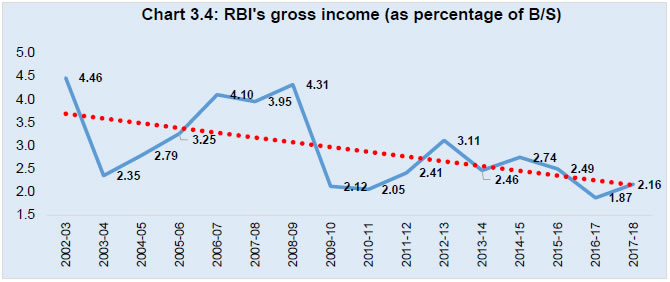

Monetary and financial stability risks Monetary operations 3.34 In addition to above market risks, the RBI’s monetary policy (sterilization) operations can significantly impact its income year-on-year as was seen in 2003–04 (-) ₹8,860 crore (a fall of 38 per cent vis-à-vis the previous year); 2009–10: (-) ₹27,848 crore (a fall of 46 per cent vis-à-vis the previous year); 2016–17: (-) ₹19,052 crore (a fall of 24 per cent vis-à-vis the previous year). Incidentally, these risks materialize when the balance sheet is already under strain due to the appreciating rupee (Chart 3.4). The RBI, nevertheless, did not suffer an overall loss during these years.  3.35 The MSS does form a RTM for the RBI, though fiscal pressures can limit the extent of its use. Going forward, even with the expected implementation of the Standing Deposit Facility (SDF), sterilization risks may not necessarily be reduced as interest will have to be paid on these deposits, and unlike the OMO which were effectively limited by the extent of G-sec held by the RBI, this would not be a constraint under the SDF. Risks arising out of financial stability mandate 3.36 While the RBI has one of the widest LoLR roles among central banks under Section 18 of the RBI Act, 1934, the ECF assesses the ‘more traditional of the ELA risks’ arising from Section 17 of the said Act. There is a view that these risks need not be covered as they have never materialized in the past and a substantial portion of the country’s banking sector is in the public sector domain. 3.37 There was another view that this represented a low probability but very high impact risk for the RBI, especially as international experience has demonstrated the vast scale of these risks as well as that contagion could spread very fast even if triggered by external sources in these days of interconnected markets. Further, the experience from GFC and more recent experiences such as Russia have shown that the ownership of the banking sector becomes more public sector oriented during periods of crisis, as the government may be required to support systemically important financial institutions to prevent contagion. This would significantly constrain the fiscal space available to the Government to recapitalize the RBI were it to suffer ELA losses. The financial stability risks of the RBI are discussed extensively in Chapter 4. The natural smoothening of central banks’ requirement for economic capital across the business cycle 3.38 Mention may also be made of a broad smoothening of the central bank’s economic capital requirements over the various stages of the business/ economic cycle. During periods of growth, the economy can be expected to receive relatively high capital inflows, thereby increasing the size of the NFA in the balance sheet and, in the face of currency appreciation, triggering valuation losses. During periods of downturn, the size of the NDA may increase which would normally suggest a reduction in the level of currency risk and, hence, the requirement for economic capital. However, the reduction in the NFA could be a result of capital outflows/ flight or the drying of the capital inflows into the country, suggesting growing systemic risk in the economy for which central banks also require economic capital in view of the enhanced financial stability risks. 3.39 The Committee, having reviewed the RBI’s public policy mandate and impact on its balance sheet and its risks, reviewed the RBI’s extant ECF in light of the same. 4 Review of the Economic Capital Framework and Staggered Surplus Distribution Policy of RBI 4.1 As highlighted earlier, the RBI has over the years developed a number of frameworks to assess its risks and the optimal level of risk provisioning. The frameworks evolved as the balance sheet expanded both in terms of size and complexity in addition to the underlying risk profile. They were also informed by developments in methodologies for identification and measurement of risk. The Committee, having deliberated on the international practices and the implications of the RBI’s public policy mandate on its balance sheet and the risks thereof, broadly reviewed the various approaches adopted in the past to assess risk provisioning to distil useful learnings for the future. The outline of this chapter is as follows:

I. A historical perspective of risk provisioning in the RBI 4.2 The salient recommendations of the various frameworks used to determine the risk provisioning of the RBI are summarized below, with a more detailed write-up presented in Annex VII. Further, in view of the extensive deliberations which took place in the Committee as to whether revaluation balances should be treated as risk buffers under the ECF, the Committee reviewed the approach adopted under all three methodologies:

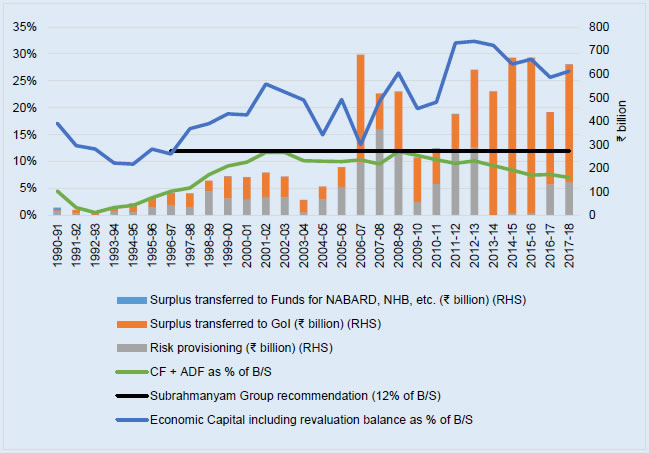

4.3 The Thorat Committee (2004) recommendations were not accepted by the RBI. 4.4 A historical perspective (1990–91 to 2017–18) of the movement in the economic capital of the RBI (Box 4.1) was also considered. 4.5 Some of the key takeaways from the analysis presented in Box 4.1 are:

4.6 In light of the above, the Committee reviewed the status, need and justification of the various reserves, risk provisions and risk buffers maintained by the RBI and recommended their continuance. The Committee recommended that the RBI should explicitly recognize the ADF not only as a provision for capital expenditure, but also as a risk provision in case of need, and that appropriate disclosures to that effect may be made in its annual report. With regard to revaluation balances, the Committee recommends the following:

4.7 The Committee recommends the need to draw a distinction between realized equity and revaluation balances for the following reasons:

4.8 In view of the distinction sought to be made between realized equity and revaluation balances, the Committee was of the view that clearer presentation of information was required in the RBI’s Annual Accounts. This is important in light of the very different estimates of RBI’s capital which has been mentioned in the public domain.18 In the RBI’s balance sheet, while Capital and Reserve Fund are explicitly shown on the balance sheet, other sources of financial resilience are grouped under ‘Other Liabilities and Provisions’ and enumerated via Schedules making it difficult to arrive at total risk provisions. The Committee, therefore, recommends a more transparent presentation of the RBI’s Annual Accounts with regard to the components of economic capital, on the lines as indicated in Table 4.1. The Committee noted that changes in the format of presentation of balance sheet would require necessary amendments to the RBI General Regulations. The information may, therefore, be presented as a Schedule to the balance sheet till such time the processes for completing change in style of balance sheet presentation are formalized. 4.9 After incorporating the aforementioned changes, the balance sheet of the RBI as on June 30, 2018 would appear as given in Table 4.2. 4.10 The Committee was of the view that given the inclusion of the revaluation balances in the RBI’s overall risk buffers, measures to address volatility will have to be introduced. After examining the various options, it was decided that this would be done by articulating RTLs. II. The extant Economic Capital Framework 4.11 Following the submission of the Malegam Committee, the RBI started developing the ECF. The ECF was first considered by the RBI’s Central Board in its March 2015 (New Delhi) meeting and, thereafter, extensively discussed at the May 2015 (Goa) meeting and a number of subsequent Central Board meetings. Discussions were also held with the Government, including meetings at the Secretary level. While the ECF analysis underpinned the surplus distribution decision for the year 2014–15, after extensive discussions at the Central Board in the August 2015 (Mumbai) meeting and finalized at the October 2015 (Aizawl) meeting, the financial resilience target for the RBI was formalized as a provisioning framework which would be consistent with the Board's aspiration to achieve, in the medium to long run, an aggregate level of provisions as usually made by bankers in order to enable it to match the highest credit rating available in international capital markets and to have sufficient additional provisions to meet financial system contingencies that may arise. 4.12 In view of the Government’s request for further discussion on the framework, extensive deliberations were held with the Government on the risk methodologies adopted under the ECF and all information sought was provided. Thereafter, the framework was formally adopted in the year 2015–16 with the transfer of RBI’s surplus to the Government for the year being unanimously approved by the Central Board at its meeting held on August 2016 (Mumbai), based explicitly on the ECF methodology, using the following parameters: S-VaR 99.99 per cent CL and a CRB target of 3 per cent with a medium-to long-term target of 4 per cent of the balance sheet. 4.13 In both the years (2014–15 and 2015–16), the ECF facilitated the almost full transfer of surplus to the Government by providing the Central Board an assurance of the RBI’s continued financial resilience at the desired levels, thereby also complying with the recommendation of the Malegam Committee that full transfer should take place for three years (2013–14 to 2015–16). The surplus distribution decision for the first year of Malegam Committee’s recommendations, i.e. 2013–14, was back-tested under the ECF and it was observed that the full transfer was also in line with ECF’s recommendations. Thus, there were no marked differences in the implied surplus transfer as per the ECF and those recommended by the Malegam Committee for the years 2013–14 to 2015–16. The ECF assessments from June 30, 2014 to June 30, 2018 are given in Table 4.3. The technical aspects of the ECF 4.14 A detailed write-up on the ECF is given in Annex IX, with the salient features outlined in Box 4.2.

III. The Staggered Surplus Distribution Policy 4.15 The surplus distribution policy is determined by Section 47 of the RBI Act, 1934, which provides the following: