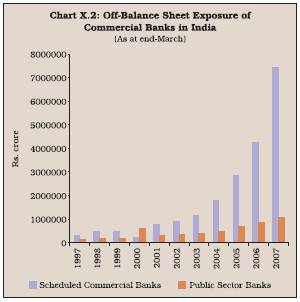

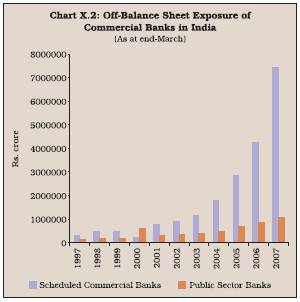

10.1 The banking sector globally has undergone rapid transformation in the recent decades driven by the forces of globalisation and the advent of technology. The extensive framework of banking regulation, which was put in place in many countries in the 1930s, and which continued till the 1950s, involving controls on interest rates, capital movement, composition of portfolios and the segmentation of financial institutions, was eased considerably in the 1980s on the grounds that it would lead to a more efficient financial system. At the same time, it was recognised that the greater degree of freedom allowed to financial institutions as a result of deregulation needed to be accompanied by wider and stronger powers for the supervisory authorities. The changes in the nature of banking exposures, the growing complexity of transactions and the expansion of off-balance sheet business, particularly derivatives, also necessitated the strengthening of the existing capital requirements as well as banks’ internal risk management systems. A relook at the way banks were regulated was also motivated by the number and magnitude of bank failures in the 1980s and the early 1990s, which were attributed by many observers to the moral hazard problems and the perverse incentive schemes (Alworth and Bhattacharya, 1998).

10.2 There are several reasons for the assumed uniqueness of banks and the need for their heavy regulation. Banks are critical for mobilising public savings and for deploying them to provide safety and return to the savers. The leveraging capacity of banks (more than ten to one) puts them in control of very large volume of public funds. In a sense, therefore, they act as trustees and as such must be ‘fit and proper’ for the deployment of funds entrusted to them. Banks also administer the payments system. The public confidence in individual banks and the banking system is, thus, crucial to a nation’s economy. The speed with which a bank under a run can collapse is incomparable with any other organisation. For a developing economy like India, there is also much less tolerance for downside risk among depositors many of whom place their life savings with the banks. Hence, from a moral, social, political and human angle, there is a more onerous responsibility on the regulator (Mohan, 2004). They have to be effectively regulated and supervised in order to maintain public confidence in the banking system and depositors have to be protected from excessive risk-taking by banks, especially in view of information asymmetry (Mohan, 2007).

10.3 From the standpoint of the regulatory authorities, the uniqueness of banks arises from their role as intermediaries in creating liquid liabilities in the face of relatively illiquid individual assets and liquidity risks on both sides of their balance sheets. Some of the challenges that banking regulators have faced increasingly beginning the early 1980s arose from (i) deregulation of economic systems which produced riskier financial systems, partly resulting from greater competition among financial institutions; (ii) wave of financial innovation particularly in the area of derivatives; and (iii) a much more pronounced internationalisation of financial flows and a greater integration of financial markets. These challenges raised several doubts about the adequacy of banks’ risk management procedures and contributed to several changes in the regulatory framework from time to time.

10.4 Supervisors have been facing an ever growing challenge to devise appropriate regulatory and supervisory structures for a financial industry that is in a constant state of change. In line with the developments in the banking system, regulators all over the world have employed new methods and approaches to achieve the basic objectives of regulation of banks. New thinking on banking regulation has emerged on several fronts. Among the important trends have been, and continue to be (i) a move away from regulation and towards supervision; and (ii) a move away from compliance with specific portfolio constraints and towards an assessment of whether the overall management of a financial firm’s business is being prudently conducted. At the same time, greater attention is being given to disclosures, to allow markets and counterparties to better control excessive risk-taking. There are several reasons why old-style regulation is being adapted to the new realities of the marketplace. In the first place, the rapid development of new instruments and methods of risk management make mechanical application of balance sheet ratios inappropriate. Second, regulation inevitably creates incentives for financial engineers to find a way around the rules. More generally, regulation is too blunt an instrument to capture the technicalities and the sophistication required to control risk in a complex financial organisation. Supervisors have to understand all aspects of a financial firm’s business, and to foresee the multiple sources of risk it is likely to confront.

10.5 A significant change is the recognition of the role that market discipline can play to augment or, to a certain degree, replace government or regulators’ oversight of the financial sector. The reason why market discipline is needed is that banks are prone to engage in behaviour that may exhibit moral hazard. As a result, banks may engage in excessive risk-taking. Banks collect deposits and invest these funds in risky assets. Market discipline is a mechanism that can potentially curb the incentive to take excessive risk by making risk-taking more costly for banks. Another trend that has attracted considerable attention in recent years is whether the financial supervision should be hived off from the central bank and entrusted to a separate supervisor. The recent events of severe market and regulatory failures in the US and Europe, where competing models of regulatory organisations are in place, point to the need for reform in both the models. While the single regulator model of the UK was steadily finding wider acceptance across the globe, the Northern Rock crisis has shown how information asymmetry and communication gap between the central bank, i.e., the lender of the last resort, and the manager of financial stability, and the integrated financial regulator could be an inherent weakness of this type of financial supervision.

10.6 The regulatory and supervisory framework for banks in India has undergone considerable transformation during the last one and half decades in line with changes in the operating environment and international norms/practices relating to regulation and supervision of banks. The focus of regulation has shifted from micro to macro and prudential elements with a view to strengthening the banking sector and providing them with greater operational flexibility. To meet challenges arising from domestic and cross-border integration among financial intermediaries, financial innovations and technological advancements and the convergence of activities among providers of various financial services, appropriate mechanisms have been put in place. The latest trends in supervision of banks across the globe are also being keenly observed with a view to judging their relevance for India.

10.7 This chapter traces the recent thinking on the various regulatory and supervisory issues for banks in the global context and delineates the various regulatory and supervisory challenges faced by the Reserve Bank. The chapter is divided into seven sections. Following introduction, Section II presents the theory behind banking sector regulation. Section III details the recent developments in supervisory practices in the global context. The extant regulatory and supervisory framework in India is discussed in section IV. Section V delves into the regulatory and supervisory issues/challenges that have arisen in the Indian context. In the light of global and domestic developments, Section VI makes suggestions with a view to further strengthening the regulation and supervision in India. The chapter ends with the concluding observations in Section VII.

II. THEORY OF BANKING REGULATION

10.8 The basic rationale for bank regulation can be traced to the special role that banks play in an economic system, i.e., as creators of liquidity. Banks play a unique and central role in an economy in general and in the financial system in particular. Banks are depositories of public money, which is then used by them to obtain returns by undertaking risk in lending and investment activities. Since they are highly leveraged, depositors’ interests have to be protected though prudential regulation. Effectively, banks are special since they act as trustees of public money placed with them. Through its lending and deposit functions, the banking system influences the aggregate money supply and is, thus, an important link in the monetary transmission mechanism. Apart from regulation of banks from the monetary management viewpoint, traditionally the regulation of banks was also considered necessary for the protection of depositors, reduction of asymmetry of information and to ensure sound development of banking. Unsophisticated depositors of banks may not be able to monitor banks effectively due to asymmetric information. It is argued that while depositors could make some judgment about the condition of banks, the tasks would still be difficult and costly. Even if a depositor could make an assessment of the current value of a bank’s assets vis-à-vis its liabilities, the condition could change as the banking business is dynamic with the banks continuously altering their asset holdings and taking on new depositors and creditors. In fact, in banking regulation, the objective of monetary stability has also been linked generally with the goal of depositor protection. It is argued that banking regulation should also provide a stable framework for individuals and businesses to conduct monetary transactions.

10.9 Banks have been affected by problems such as bank runs or failures from time to time. The main causes of these problems have been poor credit control, connected lending, insufficient liquidity and capital, which, in turn, occur due to poor internal governance (Goodhart, et al., 1998). Subsequently, when bank crises became widespread, financial regulation by authorities was considered critical to prevent systemic risk and avoid financial crises - as banks played a major role in the payments and settlement systems in almost all economies. Thus, the two main justifications for regulating banks are the inability of depositors to monitor banks and the risk of a systemic crisis (Santos, 2000).

10.10 Contemporary banking theory argues that financial intermediaries such as banks emerge endogenously to solve financial market imperfections that arise from various types of asymmetric information problems. These institutions arise to exploit such market information imperfections for economic gain. Banks, thus, emerge to provide the services of screening of potential borrowers, monitoring customers’ actions and efforts, providing liquidity risk insurance and creating safe assets. However, optimality requires that the market provides banks with the right incentives to do the above functions. It is argued that with incorrect incentives, market failures will occur in the absence of regulation of individual banks and the banking system as a whole. It is the emergence of new market failures which justifies banking regulation (Freixas and Santomero, 2002).

10.11 There are several aspects that banking regulation is not intended to accomplish. First, preventing the failure of individual banks is not a primary focus of banking regulation, subject to the condition that depositors are protected and adequate banking services are maintained. Second, bank regulation should not substitute banker’s decisions in operating a bank by government decisions. Finally, banking regulation should not favour certain groups over others. Banks also should not be protected from competition from other institutions.

10.12 Various theoretical models have been built to explain the framework of banking regulation that broadly encompasses various features: existence of a government safety net, restrictions on bank asset holdings, capital requirements, assessment of risk management framework, disclosure requirements, consumer protection and prudential supervision. Economic theory provides conflicting views on the need for and the effect of regulations on entry into the banking business. Some argue that effective screening of bank entry can promote stability. Others stress that banks with monopolistic power possess greater franchise value, which enhances prudent risk-taking behavior (Keeley, 1990). The opponents of entry restrictions, however, stress the beneficial effects of competition and the harmful effects of restricting entry (Shleifer and Vishny, 1998).

10.13 Countries regulate the activities that banks can undertake. However, there is no consensus in theory on what should be the right mix of the activities that a bank can perform. There are five main theoretical reasons for restricting bank activities and banking-commerce links. First, conflicts of interest may arise when banks engage in such diverse activities as securities underwriting, insurance underwriting, and real estate investment. Such banks, for example, may attempt to “dump” securities on ill-informed investors to assist firms with outstanding loans (John, et al., 1994; Merrick and Saunders, 1985). Second, to the extent that moral hazard encourages riskier behaviour, banks will have more opportunities to increase risk if allowed to engage in a broader range of activities (Boyd, et al., 1998). Third, complex banks are difficult to monitor. Fourth, such banks may become so politically and economically powerful that they become “too big to discipline.” Finally, large financial conglomerates may reduce competition and efficiency. According to these arguments, governments can improve banking by restricting bank activities. Further, in a country with generous deposit insurance that intensifies moral hazard problems, broad banking powers provide excessive opportunities for risk taking (Boyd, et al., 1998). Thus, it is argued that restrictions on bank activities enhance social welfare in countries with generous deposit insurance.

10.14 There are alternative theoretical reasons for allowing banks to engage in a broad range of activities, however. First, fewer regulatory restrictions permit the exploitation of economies of scale and scope (Claessens and Klingebiel, 2000). Second, fewer regulatory restrictions may increase the franchise value of banks and thereby augment incentives for more prudent behaviour. Lastly, broader activities may enable banks to diversify income streams and thereby create more stable banks.

10.15 In order to protect the interests of depositors, many countries have explicit deposit insurance schemes. Deposit insurance schemes come at a cost, however. They may encourage excessive risk-taking behaviour, which some believe offsets any stabilisation benefits. Yet, many contend that regulation and supervision can control the moral hazard problem by designing an insurance scheme that encompasses appropriate coverage limits, scope of coverage, coinsurance, funding, premia structure, management and membership requirements. However, the impact of deposit insurance can vary with the institutional environment that exists in a country. If the rule of law, bank regulation and supervision, or the information environment is sufficiently weak, deposit insurance which reduces market discipline could so weaken monitoring of banks that it would make the banking system more vulnerable to crises (Demirguc-Kunt and Kane, 2002).

10.16 Some theoretical models stress the advantages of granting broad powers to supervisors for several reasons. First, banks are costly and difficult to be monitored by the depositors/investors. This leads to too little monitoring of banks, which implies suboptimal performance and stability. Official supervision can ameliorate this market failure. Second, because of informational asymmetries, banks are prone to contagious and socially costly bank runs. Supervision in such a situation serves a socially efficient role. Third, many countries choose to adopt deposit insurance schemes. This situation (i) creates incentives for excessive risk-taking by banks; and (ii) reduces the incentives for depositors to monitor banks. Strong official supervision under such circumstances can help prevent banks from engaging in excessive risk-taking behavior and thus improve bank development, performance and stability.

10.17 Another purpose of regulation is to create a framework that encourages efficiency and competition amongst banks. Competition and efficiency depend, inter alia, on the number of banks operating in a market, the freedom of other banks to enter and compete and the ability of banks to achieve an appropriate size for serving their customers. The objective of customer protection is generally considered consistent with good banking principles. It is argued that disclosures and informed customers would be of benefit to bankers offering competitive services.

10.18 On the flip side, powerful supervisors may exert a negative influence on bank performance. Powerful supervisors may use their powers to benefit favoured constituents, attract campaign donations, and extract bribes (Shleifer and Vishny, 1998; Djankov, et al., 2002; and Quintyn and Taylor, 2004). Under these circumstances, powerful supervision will be positively related to corruption and will not improve bank development, performance and stability. From a different perspective, Kane (1990) and Boot and Thakor (1993) focus on the agency problem between tax payers and bank supervisors. In particular, rather than focusing on political influence, Boot and Thakor (1993) model the behaviour of a self-interested bank supervisor when there is uncertainty about the supervisor’s ability to monitor banks. Under these conditions, they show that supervisors may undertake socially sub-optimal actions. Thus, depending on the incentives facing bank supervisors and the ability of tax payers to monitor supervision, greater supervisory power could hinder bank operations.

10.19 It is important to bear in mind that while financial institutions do benefit from an appropriate regulatory regime, there is not much evidence that the existence of a regulatory jurisdiction makes institutions stronger and less prone to shocks (Fiebig, 2001). Some economists claim that there is no evidence that supervision works (Barth, et al., 2004). Instead, they argue that regulations that promote market monitoring are associated with deeper financial systems and less likelihood of crises.

10.20 Some advocate more reliance on private-sector monitoring, expressing misgivings with official supervision of banks. They argue that a greater role for market discipline would act as a restraining factor for imprudent behavior by both managers and consumers of banking products. This model is, however, not widely followed. The banking sector is still considered far too important, socially and politically, to be left entirely to the working of the market mechanism. However, greater emphasis is being laid on market discipline, although there are limitations of private monitoring especially in emerging market economies. Supervisory agencies may also encourage private monitoring. Some supervisory agencies require banks to produce accurate, comprehensive and consolidated information on the full range of their activities and risk-management procedures. Some countries even make bank directors legally liable if information is erroneous or misleading. Also, some countries credibly impose a “no deposit insurance” policy to stimulate private monitoring. Countries with poorly developed capital markets, accounting standards, and legal systems may not be able to rely effectively on private monitoring. Furthermore, the complexity and opacity of banks may make private sector monitoring difficult even in the most developed economies. From this perspective, therefore, excessive reliance on private monitoring may lead to the exploitation of depositors and poor bank performance.

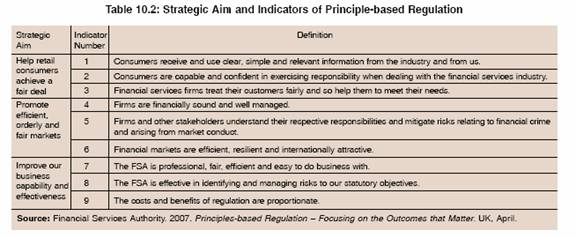

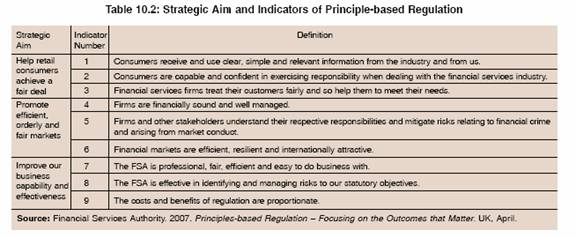

10.21 The recent events in global financial markets in the aftermath of US sub-prime crisis have evoked rethinking on several regulatory and supervisory aspects of the banking industry. For instance, it has become important for the UK to consider an effective regime for shutting down failing banks and overhauling of its deposit insurance scheme. In the US, an important issue that has emerged is the streamlining of the supervisory system to overcome disadvantages of a fragmented regulatory authority, and extension of effective regulation of non-banking financial intermediaries. A great amount of attention is also being placed on the effectiveness of policies that are in place to manage any emergency such as deposit insurance and central bank funding. Another area of debate centres on whether regulatory regimes should be based on rules or principles. The supporters of a more formulaic approach believe that a system based on principles gives banks enough room to get around their obligations. On the other hand, those who support principle-based regulation argue that precise rules are inflexible and can be easily circumvented. Perhaps, a blend of the two approaches is required. Some observers are also questioning whether it was right to repeal the Glass-Steagall Act, which separated commercial and investment banking, though it is unclear how this division would have prevented the crisis (The Economist, 2008).

III. REGULATORY AND SUPERVISORY

PRACTICES – RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

10.22 There has been new thinking on some of the aspects of banking regulation and supervision due to the changing nature of banking operations. The most basic forces affecting the shape of the banking sector are the same as those affecting the rest of the economy. First, the quickening pace of technological innovation, especially in data processing and communication, has had particularly profound effect on the financial sector. The financial sector is information intensive, and most of the innovations in recent years have been in the area of processing and transmission of information. Second, the growing acceptance of market processes as a basic determinant of resource allocation led to deregulation of the financial sector. The financial sector was among the most heavily regulated, with most countries having, until as recently as two decades ago, extensive controls on prices, entry to the industry, competitive practices, and portfolio composition. The impact of deregulation and innovation on banking and the rest of the financial sector have been profound. The range of products and services have widened markedly. Intermediation costs have declined enormously. Financial transactions have grown rapidly in relation to GDP. All of this has brought considerable benefits through more efficient origination and allocation of capital, greater availability of capital for investment and greater efficiency in the management of risks, among others.

10.23 As these fundamental drivers of change have brought about a major transformation in the way banks are run, the way they are structured and the range of products they offer, they have important implications for supervisory and regulatory authorities. Some of the recent trends include globalisation of banking operations and market integration, expansion in the scale of activities and proliferation of financial conglomerates and increasing complexity of financial products in line with financial innovations, among others.

10.24 First, globalisation is an important trend in the banking industry. A combination of liberalisation of financial markets over the past two decades and business opportunities in rapidly growing economies have led to an increasing proportion of global bank activities in foreign countries. This is particularly the case in the securities markets, although there have been other areas such as retail where the presence of global banks in local markets continues to grow. For the financial sector, globalisation means the decline in the barriers between different financial markets. Capital can flow more easily to locations where it receives the best reward; institutions have easier access to foreign markets; and boundaries between different kinds of financial activities are becoming blurred. To some extent, this is happening because financial engineering has rendered previous administrative controls obsolete; and to some extent it represents a willing acceptance of a more free market philosophy. The growing international nature of banking activities is clearly discernible from indicators such as (i) increase in cross-border bank lending as a proportion of total bank lending; (ii) increase in the proportion of banking assets held worldwide; and (iii) growing share of international profits in total profits of banks. In general, foreign banks operating in emerging markets bring expertise and financial resources that might not otherwise be available. They can also introduce more sophisticated risk management tools that may have been developed for the larger financial group. While these benefits are significant, the scale of foreign banks’ presence can have implications for host countries. As finance is becoming increasingly global and integrated, prudential supervision has to adapt to that reality. 10.25 Second, sectoral distinctions are becoming blurred. A few decades earlier, most financial intermediation was conducted through banks, with insurance companies and investment vehicles having well-defined roles. However, many different types of institutions, including non-financial firms, are now involved in both wholesale and retail markets. Importantly, the ability to deconstruct and re-combine risks has enabled financial intermediaries to expand and compete effectively in sectors beyond their own. While this trend has emerged under the regulatory umbrella or framework that provides the greatest benefit and flexibility, the supervisors have to guard against potential system-wide reduction in capital adequacy or undue risk concentration resulting from expansion into new areas.

10.26 Third, banks as well as securities firms are actively involved in origination, securitisation and active management of credit exposures. Advances in the processing of information have permitted the independent pricing of risk factors that were previously bundled together in the same instrument. The shift to capital market-based distribution of risk has been accompanied by increased velocity in intermediation, aided by new technologies that allow for greater automation and standardisation. The greater role of capital markets in intermediation also implies that many of the risks once held by banks are now held by other types of market participants. The greater reliance on the capital markets in credit origination and distribution has also served to unlock the creative potential of market participants. At the same time, the intensification of financial intermediation has given rise to an explosion in the demand for hedging (and position-taking) instruments. Nevertheless, the new financial instruments have enormously improved the technology of risk-management. The downside is that these same instruments, if not properly understood and used, increase the potential for loss, whether resulting from inadequate understanding or deliberate leveraged bets.

10.27 Fourth, financial systems appear to have become more pro-cyclical than before, capable of amplifying credit growth and leveraging market positions more intensely than before. In essence, the “marginal” risk that financial actors willingly engage is greater than before. To a degree, this is the result of innovations in financial technology, including the process of securitisation, which allow risks to be better distributed and managed. The more widespread use and trading of collateral is also a factor. It also reflects the intensification of competition, and perhaps a view among firms that they will be able to get out of risky engagements before they turn sour. Of course, pro-cyclicality works in both directions. Once the downturn sets in, the financial system seems more prone to liquidity erosions and reduced credit supply than in previous episodes of stress.

10.28 Finally, greatly increased speed of developments in the financial sector. The speed of transmission of news in the financial sector has always been high relative to other sectors. These days, market communication and execution can be almost instantaneous. The market players’ judgement of strategic opportunities in their environment and their moves to take advantage of them have also speeded up due to new and cheaper technology as well as deregulation. Business models get adopted and discarded more quickly. This will test regulators and supervisors for whom the challenge is to create rules of the game that are robust.

10.29 The above trends in the financial sector have important implications for the focus of regulation and supervision and the way in which regulatory and supervisory responsibilities are allocated. Some of these issues are - the location of institutional responsibility for supervision; appropriate regulatory structure; the increased reliance on market discipline; and the principle-based approach vis-à-vis rule-based approach.

Separation of Supervision from Central Bank

10.30 The question of where authority for the supervision of banks and other financial institutions should reside has become the subject of intense debate. In many countries, responsibility for banking supervision rests with the central bank, while supervision over other financial institutions is typically vested with other agencies. However, in recent years, there are several cases of countries moving away from this model.

10.31 Although the early central banks were established primarily to finance commerce, foster growth of the financial systems and to bring uniformity in the note issue, central banks in several countries in the 20th century, notably the US, were founded to restore confidence in the banking systems after repeated bank failures. As the incidence of banking crises started increasing, the statutory regulation of banks was considered necessary for the protection of depositors, reduction in asymmetry of information and for ensuring sound development of banking. In the 19th century, central banks had started focusing their attention on ensuring financial stability and their role had increasingly come to eliminate financial crises. The Bank of England used to adjust the discount rate to avoid the effects of crises and this technique was used by other European central banks as well. In the United States, a series of banking crises between 1836 and 1914 had led to the establishment of the Federal Reserve System. The experience of the Great Depression had a profound effect on banking regulation in several countries and commercial banks were progressively brought under the regulation of central banks. Thus, the prevention of systemic risk manifested by crises became the basic reason for central bank’s involvement with financial regulation and supervision.

10.32 The experience of some other countries in delegating the responsibility of bank regulation was totally different. Despite the occurrence of banking crises and the need for central bank’s intervention in resolving the crises, some countries established a separate regulatory authority outside the central bank to supervise the banking system, often several years before or after the creation of the central bank. The Canadian Government established the Office of the Inspector General of Banks in 1925 after the collapse of the Home Bank. The Bank of Canada was created nine years later (Georges, 2003). Canada’s experience was not unique. A number of other countries, including Chile, Mexico, Peru, and the Scandinavian countries developed central banks and bank regulators completely separately. Thus, the experiences of countries in creating an appropriate structure and entrusting the responsibility of bank regulation and supervision vary considerably, although the basic motive has been to maintain systemic stability.

10.33 The literature is split on the relative advantages and disadvantages of the central bank being a bank supervisor (Box X.1). The most strongly emphasised argument in favour of assigning supervisory responsibility to the central bank is that as a bank supervisor, the central bank will have firsthand knowledge of the condition and performance of banks. The central bank’s supervisory role makes it easier to get advance information from banks. This, in turn, can help it identify and respond to the emergence of a systemic problem in a timely manner. Furthermore, to the extent that the central bank acts as a lender of the last resort (LoLR), it may be desirable that some regulatory and supervisory functions remain with central bank in order to limit moral hazard incentives and to have an intimate knowledge of the condition of banks, which can be acquired only through its participation in the supervisory process. This argument assumes that it is not possible for a third party, responsible for bank supervision, to transfer information effectively to the LoLR, particularly during financial instability. In addition, contrary to the common view that monetary policy and policies toward financial stability should be seen separately, they are inseparable. At the very least, there is a strong case for better co-ordination of monetary policy and policies toward financial stability. An important lesson of the sub-prime crisis is that asset prices alone are unlikely to be sufficient to summarise the conditions of intermediaries. Balance sheet dynamics provide information on key components of GDP and the resilience of the financial system (Adrian and Shin, 2008). Those pointing to the disadvantages of assigning bank supervision to the central bank stress the possible conflict of interest between supervisory responsibilities and responsibility for monetary policy. However, such a conflict of interest may also exist even when central bank is not the regulator and supervisor for banks as the central bank will always endeavour to maintain the stability of the financial system. The conflict could become particularly acute during an economic downturn in that the central bank may be tempted to pursue a too-loose monetary policy to avoid adverse effects on bank earnings and credit quality, and/or encourage banks to extend credit more liberally than warranted based on credit quality conditions to complement an expansionary monetary policy.

10.34 In recent years, there has been a trend of passing over banking regulation from the central banks to other agencies. Under this arrangement, central banks are assigned the task of monetary policy and also remain lenders of last resort. This phenomenon has occurred in a few countries, notably Great Britain, Japan and South Korea. Countries which belong to the European Monetary Union (EMU) have de facto adopted this system since monetary policy is now carried out at the federal level (the European Central Bank), while banking supervision is undertaken at the national level.

10.35 In the UK, until the Fringe Banking Crisis in 1974-75, the Bank of England restricted its direct supervision to a small number of merchant banks (the Accepting Houses) and to the discount market, stemming from the Bank’s own credit exposures. The Banking Act, 1976 increased the formal role of the Bank of England in supervision and regulation of the banking system. The supervisory function was carried out by one single senior official, the Principal of the Discount Office, with a handful of staff. So, historically, the conduct of banking supervision did not, in practice, play a really large, or central, role in Central Bank activities because the structure both reduced the need for such an exercise and allowed it to be largely achieved through self-regulation (though this may have been particularly so in the UK, and less representative of other countries) (Goodhart, 2000b).

Box X.1

Banking Supervision and the Central Bank

Combining the monetary and supervisory functions is best attributed to the central bank’s concern for the ‘systemic stability’ of the financial system and the protection of the payments system. On the grounds of moral hazard, it is appropriate to provide ‘lender of last resort’ (LoLR) facilities only when a bank is illiquid, but not insolvent (e.g., Bagehot, 1873). Hence, if the central bank supervises an institution, it may know more precisely whether an institution asking for credit is insolvent or just illiquid. However, regardless of the source of problems, the central bank may feel compelled to support failing participants to avoid systemic ‘knock on’ effects. Hence, to the extent that the central bank continues to operate the payments system and act as a LoLR, it is likely that it will want to maintain some regulatory and supervisory functions in order to limit moral hazard incentives and to have an intimate knowledge of the condition of banks, which can be acquired only through its participation in the supervisory process. This argument assumes that it is not possible for a third party, responsible for bank supervision, to transfer information effectively to the LoLR. However, it seems more plausible during periods of financial instability, since the speed and the degree with which the condition of an institution deteriorates is significantly higher during periods of financial instability. Moreover, it is in ‘bad’ times that institutions are more likely to ‘cook’ their books and hide their true condition. Hence, under these circumstances, direct supervision could help deliver the essential information on time. Using a cross-country micro dataset, it was found that countries where central banks were involved in supervision had, on average, fewer bank failures (Goodhart and Schoenmaker, 1995). It is also argued that banking supervisory information (early warning of problems with non-performing loans or changes in the lending pattern of banks) may improve the accuracy of macroeconomic forecasts and thus help the central bank to conduct monetary policy more effectively (Bernanke and Gertler, 1995). The central bank’s involvement in supervision does not necessarily weaken its stance on monetary policy as a central bank’s inflation performance and its role in supervision are two, more or less, separate issues. On the other hand, the combination of control of monetary policy and the role of LoLR at the central bank has been criticised on the grounds that it raises inflationary concerns. A central bank committed to price stability will sterilise the injection of liquidity necessary for the stability of the system in the event of crisis so that there is no undesired increase in the money supply. If the LoLR function and supervision are combined, an intervention as LoLR may give rise to confusion in the expectations of the private sector regarding the central bank’s monetary policy stance. Concerns have also been expressed that a conflict of interest may arise between the reputation of the central bank as guarantor of currency and financial stability. For example, concern for the reputation of the central bank as supervisor may encourage an excessive use of the LoLR facility so that bank crises do not put its supervisory capacity in question. It has been argued that the reputation of the central bank is more likely to suffer, than to benefit, from bank supervision.

A more general point is that the cyclical effects of micro (regulatory) and macro (monetary) policy tend to be in conflict. Monetary policy is usually countercyclical, while the effects of regulation and supervision tend to be procyclical, offsetting to some extent the objectives of monetary policy. In particular, during periods of economic slowdown, the financial condition of banks usually deteriorates. In this case, the bank’s supervisor steps in and applies pressure on the institution to improve its condition. However, the bank’s implementation of supervisory requirements results in even tighter credit during an economic recession. Following this line of argument, one might expect the central bank to use its supervisory role to complement monetary policy, i.e., to be less strict in supervision when monetary policy is expansionary and vice versa (Goodhart and Schoenmaker, 1993).

References:

1. Ayadi, Rym and Pujals, Georges. 2004. “Banking Consolidation in the European Union, Overview and Prospects”. Research Report in Finance and Banking, Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS), No.34, April.

2. Bagehot, W. 1873. Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market, London.

3. Bernanke, B. S. and Gertler, M. L. 1995. “Inside the Black Box: The Credit Channel of Monetary Policy Transmission”. Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 9 (Fall), 27-48.

4. Di Noia, C. and Di Giorgio, G. 1999. “Should bank supervision and monetary policy tasks be given to different agencies?”. International Finance, Vol. 2, Issue 3, 361-378, November.

5. Goodhart, C.A.E and D. Schoenmaker. 1993. “Institutional Seperation between Supervisory and Monetary Agencies.” LSE Financial Markets Group Special Paper, No. 52.

6. Goodhart, C.A.E and D. Schoenmaker. 1995. “Should the Functions of Monetary Policy and Banking Supervision be Separated?”. Oxford Economic Papers, 47: 539-560.

7. Goodhart, A. E. Charles. 2000. ‘‘The organizational structure of Banking Supervision.’’ Occasional Paper, No. 1, Basel Switzerland, Financial Stability Institute (FSI), November.

8. Ioannidou, Vasso P. 2003. “Does Monetary Policy affect the Central Bank’s role in Bank Supervision?”.

Journal of Financial Intermediation, 14: 58-85, September.

10.36 In 1997, the newly elected Labour Government in the United Kingdom transferred responsibility for the prudential supervision of commercial banks from the Bank of England to a newly established body, the Financial Services Authority (FSA). The FSA was to take on responsibility for, and combine, both the prudential and the conduct of business supervision for virtually all financial institutions (banks of all kinds, finance houses, mutual savings institutions, insurance companies, etc.) and financial markets.

10.37 The main driving forces behind the separation of supervision was the changing, more blurred, structure of the financial system, and continuing concerns with conflicts of interest. As the dividing lines between differing kinds of financial institutions became increasingly fuzzy (e.g., universal banks), continuing banking supervision by the central bank led to both inefficient overlap between supervisory bodies, and a potential creep of central bank safety net and other responsibilities into ever-widening areas. With the accompanying trend towards central bank operational independence in monetary policy, continued central bank supervisory authority, it was believed, would enhance concerns about potential conflicts of interest, and raise issues about the limits of delegated powers to a non-elected body.

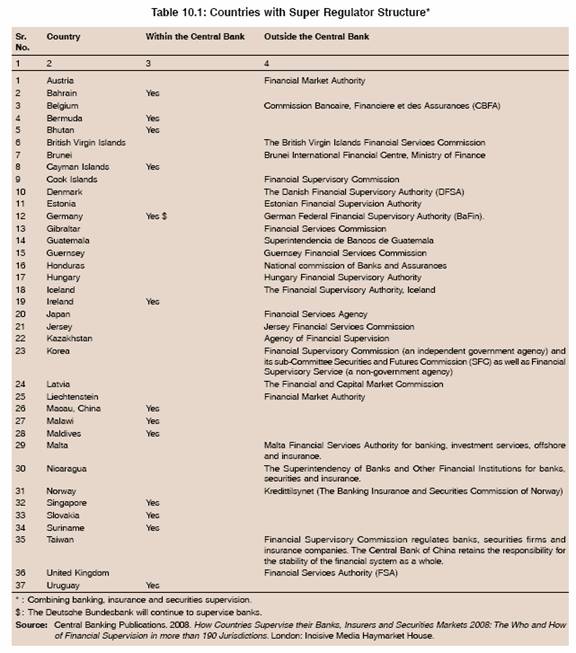

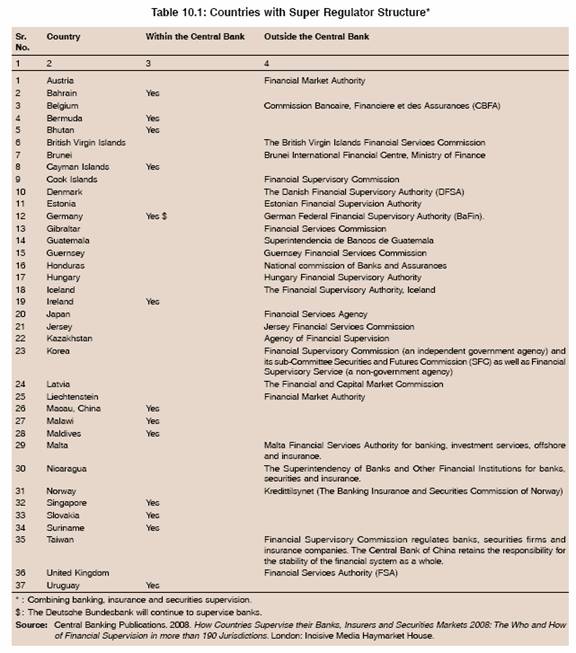

10.38 The U.S. Federal Reserve Board still plays a major role in banking supervision. In the United States, the central bank became an additional bank supervisory authority after multiple supervisory authorities had already been established. Only three countries (Italy, Netherlands and Spain) of the thirteen countries representing the Basel Committee have the central banks as the only authority responsible for bank supervision. Germany moved to a single supervisory agency, viz., German Federal Financial supervisory Authority (BaFin), in May 2002 to supervise banking, insurance and securities firms. However, Deutsche Bundesbank, the central bank, continues to play a significant role in bank supervision. France, Italy and Spain have separate supervisors for banks, insurance companies and securities firms. In France, the Commission Bancaire supervises all credit institutions. The Commission, however, benefits from a considerable synergy with the activities of the central bank. In Italy and Spain, bank supervision is with the central bank. Belgium moved to a single supervisory system in January 2004 with the responsibility of supervising banks, insurance companies and securities firms resting with an autonomous public institution outside the central bank. China established a new bank supervisory authority in early 2004, but the central bank, which had been the sole authority, retained some limited supervisory responsibility (Barth, et al., 2004). A survey of 198 countries reveals that banking supervision is outside the central banks in 52 countries. These countries, among others, include Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Hungary, Japan, Mexico, Panama, Turkey, United Kingdom and Venezuela (Central Banking Publication, 2008).

10.39 The recent episode of liquidity crisis in the Northern Rock, UK in July 2007 in the aftermath of US sub-prime crisis has, however, raised concerns about the effectiveness of coordination among the central bank as LoLR, the Treasury, and the FSA, and also the desirability of having supervision outside the central bank (Box X.2).

10.40 The UK, after supervisory functions were entrusted to a separate authority, adopted a more formalised approach based on the memorandum of understanding of the Tripartite Agreement between the HM Treasury, the Bank of England and the FSA, which establishes a framework for co-operation among them to work together towards the common objective of financial stability. It clearly sets out the role of each authority based on the principles of accountability, transparency, avoidance of duplication and information exchange. Under the agreement, the responsibilities of each authority are well defined. The agreement also calls for a regular exchange of information which will help the authorities to discharge their responsibilities as efficiently and effectively as possible. However, the interaction between the FSA, Bank of England and the Treasury, in the Tripartite Agreement, was seen as a key weakness following the Northern Rock collapse. Consequently, the FSA vowed to improve co-ordination with the Bank of

Box X.2

Northern Rock Liquidity Crisis

The US sub-prime mortgage market attracted many investors in the search for yield. The success of structured credit that offered high yields with high credit ratings created a huge demand for these products in particular sub-prime mortgages. It allowed banks to move increasingly from the traditional “lend and hold” model towards an “originate and distribute” model. This boosted the supply of credit and allowed risk to be more widely dispersed across the system as a whole. But it also involved a long chain of participants from the original lenders to end-investors. Investors at the end of this chain, who bore the final risk, had less information about the underlying quality of loans than those at the start and became dependent on rating agencies and their models. It also reduced the incentives on originators to assess and monitor credit risk carefully. The delinquency rate in the US sub-prime mortgage market began to rise early in 2005, but there was no significant market response to these developments until mid-June 2007 when credit spreads began to widen. The trigger was the revelation of losses by a number of firms and a cascade of rating downgrades for sub-prime mortgage products and some other structured products. By early August 2007, growing concerns about counterparty risk and liquidity risk, aided by difficulties in valuing structured products, led to a number of other markets being negatively affected. In particular, there was a collapse in the market for collateralised debt obligations (CDOs), a massive withdrawal from the asset-backed commercial paper market, and a sudden drying-up of the inter-bank term money market. As large global banks continued to announce associated losses, concerns began to mount about the adequacy of their capital cushions.

Northern Rock, Britain’s fifth-largest mortgage lender, had a positive medium-term outlook and a robust credit book in July 2007. In less than two months, however, there was a run on the Northern Rock, the first of its kind in over 100 years in the UK. The run on Northern Rock was the most dramatic symptom of the contagion gripping the financial markets in the UK on account of the sub-prime crisis in US. The bank had made good use of innovative structured products in funding its robust growth in the years prior to the crisis. The bank did not lend overseas but it was still impacted by the turmoil in America’s mortgage market. When the sub-prime crisis spilled over into the securities and money markets, the bank, with its low deposit-to-loan ratio, was not able to renew its short-term financing and was forced to turn to the Bank of England for assistance. When the news

broke, many customers quickly withdrew their savings. The UK had not experienced such panic-driven withdrawals since 1866. The Financial Services Compensation Scheme was not sufficient to calm the bank’s customers.

By September 11, 2007, it became clear that private sector solutions, including securitisation, were not an option. On September 14, 2007, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, on the advice of the Governor, Bank of England and the FSA, Chairman, authorised the Bank of England to provide liquidity support facility to Northern Rock against appropriate collateral and at an interest rate premium to help it to fund its operations. The FSA judged that Northern Rock was solvent and had a good quality loan book. On September 17, 2007, the Chancellor announced that the Government would put in place arrangements that would guarantee deposits held with Northern Rock. On January 21, 2008, the treasury announced plans to back a private-sector rescue of Northern Rock through the sale of Government-guaranteed bonds to pay off the lenders about £24 billion debts. On February 22, 2008, the bank was nationalised as a result of two unsuccessful bids to take over the bank. The single largest impediment in dealing with Northern Rock was the absence of a mechanism for intervening pre-emptively in a bank in trouble to separate the retail deposit book – the insured deposits – from the rest of the bank’s balance sheet. A key lesson that can be learnt from the Northern Rock episode is that liquidity alongside capital should be central to the regulation of banks. Northern Rock did not face a problem of inadequate capital. But it was vulnerable to a shock that reduced the liquidity in markets for securitised mortgages.

References:

1. Memorandum from the FSA, UK to the Treasury Committee. 2007. Government of UK.

2. King, Mervyn. 2007. “Monetary policy developments”. at the Northern Ireland Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Belfast, October.

3. Penn, Philip H. 2007. “Enhancing and strengthening banking supervisory capabilities in Pacific countries”. at the Pacific Regional Banking Supervision Seminar, Apia, Samoa, October.

4. Gieve, John. 2008. “The return of the credit cycle – old lessons in new markets”. at the Euromoney Bond Investors Congress, London, February. England’s financial stability directorate. According to some observers, the Northern Rock crisis has revealed that an ‘incentive compatible’ division of responsibilities has not been reached and the Agreement itself needs re-drafting. In resolving this issue, it has been argued by some that the decision to remove bank supervision from the Bank of England needs re-visiting, as does the issue of whether the authority responsible for financial stability should be divorced from bank supervision (e.g., Mullineux, 2008).

10.41 The issue of LoLR has surfaced in the wake of recent sub-prime mortgage loan problem in the US, which led to a serious credit squeeze in the US and several other advanced economies. This posed a serious challenge for central banks across the world and has raised several issues in the context of the LoLR function. These issues broadly relate to the choice of instruments, bail-out, the size and manner of liquidity modulation to deal with potential gridlocks, the types of collateral, the type of institution to be supported, and the period of support, among others (Box X.3).

Box X.3

The Lender of Last Resort

The term ‘lender of last resort’ (LoLR) refers to a function of a central bank, whereby it lends money to support a financial institution facing temporary liquidity stress even after exhausting recourse to the market and whose failure is likely to have systemic implications. The term originated in the context of the establishment of the Bank of England when it was referred to as “the dernier resort” from which all banks could obtain liquidity during a crisis (Baring, 1797). The classical LoLR doctrine asserts that during periods of liquidity crisis faced by a “solvent but illiquid” bank, the central bank in its role as LoLR may support it by lending to it against good collateral, valued at pre-crisis levels, and at a penal rate (Thornton, 1802; Bagehot, 1873). The central bank, as the only institution able to create liquidity in the banking system, has an important role to play as LoLR, particularly if the liquidity problem threatens systemic stability. However, the role of LoLR entails significant moral hazard because the central bank might be seen as too willing to underwrite the banking system and bail out banks that are not as well run as others, thereby indirectly encouraging imprudent practices. In the context of recent sub-prime crisis, the following five instruments have been used by the central banks to avoid serious spill-over of the turmoil in money or credit markets into the wider economy: (i) adjustment of borrowing and lending rates; (ii) money market operations designed to inject special liquidity in order to avoid a break-down in the payment systems among banks; (iii) modifications in the quality of eligible collateral; (iv) central banks’ involvement without financial support in devising mechanisms for financial transactions among the largest of the financial intermediaries which automatically impact the second and third rung intermediaries; and (v) central banks’ involvement by providing financial support to large financial intermediaries to influence finances of other financial intermediaries.

Several issues have come into sharp focus as a result of LoLR operations in the recent financial turmoil. First, central banks’ liquidity operations have traditionally been in a limited range of securities and often conducted with a select group of institutions, relying on them to ‘distribute’ the liquidity to the rest of the system as needed. However, during the recent financial turmoil, central banks expanded the range of securities that could be accepted as collaterals. The US Fed, in particular, agreed to hold large values of mortgage-backed securities that the markets were struggling to sell and provided them with either cash or treasury securities that could be immediately converted into cash. Second, the LoLR facility is primarily meant for dealing with crises affecting banks on account of their special balance sheet characteristics relative to other financial intermediaries. However, during the recent global financial market turbulence, major central banks also supported non-banks (especially investment banks) on financial stability considerations and often lent support to unviable institutions due to systemic concerns. It has been argued that LoLR needs to be extended to non-banks as well, especially in the face of systemic consequences in the context of increasing disintermediation and the resultant blurring of the distinction between banking and non-banking services extended by both banks and non-banks as well as cross exposure.

While there is broad agreement on central banks’ role as LoLR for ensuring financial stability, in practice, it is difficult to determine whether financial intermediary is solvent in a dynamic sense of being able to honour its obligations by rolling over its funding. Before acting as a LoLR, the central bank needs to make a clear judgement on some crucial issues such as (i) whether there are any systemic issues; (ii) whether the liquidity is to be provided to the market or to the institution; (iii) whether the institution is solvent but illiquid; and (iv) whether the security being offered is of good value. The main issue involved while acting as LoLR is to ensure that the central bank lends only to solvent but illiquid banks. However, at times it is difficult to distinguish an illiquid from an insolvent institution. This is especially when the financial markets are not working smoothly making it difficult to compute the market value of a bank’s assets.

Since the need for emergency liquidity assistance arises suddenly and without adequate warning, timeliness in providing such assistance becomes critical while recognising that responses cannot be ‘bookish’ or manual-based. While the LoLR function is important for preserving financial stability; the manner and timing of its activation is unpredictable. Accordingly, the most important issue in the context of the LoLR function is to ensure that the central bank is empowered with a comprehensive, effective and independent mandate to perform this function in the interest of systemic stability while being conscious that considerable degree of judgement is involved in taking a decision on LoLR.

References:

1. Bagehot, Walter. 1873. Lombard Street, A Description of the Money Market. London.

2. Baring, Francis.1797. Observations on the Establishment of the Bank of England and on Paper circulation of the Country. London: Minerva Press.

3. Reddy, Y. V. 2007. “Global Developments and Indian Perspectives: Some Random Thoughts.” Valedictory address by at the Bankers’ Conference on November 27, Mumbai.

4. Thornton, Henry. 1802. An Enquiry into the Nature and Effects of Paper Credit of Great Britain. Hatchard, London. Reprint, George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London, 1939.

Supervisory Structure

10.42 An important feature of the structure of the banking industry until recently was the separation of the banking and other financial services industries, i.e., securities and insurance. In the US, such separation was mandated under the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. Many other countries also placed restrictions on combining banking with insurance and securities business. However, the pursuit of profit and financial innovation stimulated both banks and other financial institutions to encroach on each other’s traditional area of operations. In many countries, restrictions on combining banking with insurance and securities business were withdrawn, resulting in the emergence of ‘financial conglomerates’ (Box X.4).

10.43 Conglomeration has been motivated by economic benefits of combining different financial activities under one roof so as to capture economies of scale and scope across business lines. These economies are generated by higher operational efficiency and by innovation of products that allow, for instance, capitalising on consumers’ willingness to pay for ‘one-stop shopping’. A financial conglomerate with a common information system that can be used across product lines incurs the cost of gathering information only once. Delivery, marketing and physical inputs can be combined in production of a larger set of services. Finally, when risks in different services are imperfectly correlated, there is a potential for economies in risk management through a diversified risk por tfolio. Fur ther, financial conglomeration has been considered as a means for earning profits and maintaining earnings through diversification. While advances in information technology have led to sophistication of financial services and substantial reduction of costs, they have also increased the investment burden on the financial service providers. Reducing this investment burden is believed to be another major factor responsible for financial conglomeration. The changes in financial needs have led to the emergence of new financial service providers and have also caused existing financial service providers to expand their organisations by integrating with other providers in different sectors, so that they can better respond to diversifying customer needs. The operations of financial service providers are also becoming more global as a consequence of greater cross-border movement of funds and information. Financial authorities have also helped to create an environment conducive to the integration of financial services and diversification of business by relaxing the regulations.

10.44 The operations of financial conglomerates, however, raise some serious concerns from the supervisory standpoint such as systemic risk posed by a large and complex structure, conflict of interest, regulatory arbitrage, double and excessive gearing, and contagion. When a financial institution becomes too large, the regulator might feel the need to extend liquidity support or financial safety net beyond usual policy measures to prevent system-wide financial crisis. Such an implicit insurance system gives large institutions an edge over small ones which are unrelated to their ability to manage risk, thereby increasing the vulnerability of the financial system. Large and complex financial institutions are also susceptible to the problem of weak internal controls, lack of flexibility and poor integration. As activities of the conglomerates become more complex and varied, it becomes more difficult for regulators to monitor them effectively. Conflict of interest is viewed as a fundamental weakness of a financial conglomerate. The conflict of interest arises when any entity within the financial conglomerate deals with another entity within the group on terms which are different from market terms or outside the usual approval process. At times such actions could be undertaken to bail out each other’s clients. Another problem posed by financial conglomerates is the ‘regulatory arbitrage’, which refers to the shifting of certain activities or positions within a conglomerate where regulatory requirements are less strict or absent. Thus, a financial conglomerate may reduce aggregate capital requirements by booking risks where capital requirements are lightest. This problem arises due to ‘double gearing’ whereby same capital is used simultaneously to cover the capital requirements of the parent company as well as those of a subsidiary. This dual use of the same capital could lead to undercapitalisation of the conglomerate if the framework for consolidated supervision does not ensure elimination of double gearing. The problem of ‘excessive gearing’ arises when a parent company issues debt and downstreams the proceeds to the subsidiary/ies as equity. Another related problem is that of aggregation. That is, the risk assumed by a conglomerate may be larger than the sum of its parts (Malkonen, 2004). Yet another major issue arising out of operations of financial conglomerates is contagion. It entails the risk that financial difficulties faced by a unit within the conglomerate could have an adverse impact on the stability of the conglomerate on the whole. The adverse impact could be felt even by the healthy and well-functioning constituents of the group. Contagion results from the existence of extensive intra-group exposures.

Box X.4

Financial Conglomerates - Definition and Structure

There is no single universally accepted definition of a financial conglomerate (FC) as there are differing views as to what really constitutes a FC. The Tripartite Group (1995) defines a FC as “any group of companies under common control whose exclusive or predominant activities consist of providing significant services in at least two different financial sectors (banking, securities, insurance)”. In the European Union, the following three requirements must be satisfied for a group to be considered a ‘FC’. One, the group has at least one company engaged in either banking or securities and at least one company engaged in insurance. Two, a company engaged in banking, securities, or insurance is at the head of the group or the ratio of the balance sheet total of the financial sector entities in the group to that of the group as a whole (the total amount outstanding of banking, securities, and insurance services) exceeds 40 per cent. Three, for each financial sector, the average of the ratio of the balance sheet total of that financial sector to the balance sheet total of the financial sector entities in the group and the ratio of the solvency requirements of the same financial sector to the total solvency requirements of the financial entities in the group exceeds 10 per cent or the balance sheet total of the smallest financial sector entity in the group exceeds 6 billion euros.

The US financial laws do not use the term ‘financial conglomerate’. The Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999 (known as the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act or GLB Act) allows bank holding companies (BHCs) that meet certain requirements in terms of capital adequacy and other measurements to act as ‘financial holding companies (FHCs)’ that are allowed to establish subsidiaries for engaging in a broader range of businesses than those permitted to BHCs, including securities, insurance, and mutual funds. ‘FHC’ is merely a status that allows it to hold other companies offering a broad range of financial services. Likewise, financial laws in Japan do not use the term ‘financial conglomerate’. Individual sectoral laws govern the scope of business open to holding companies and their subsidiaries, making Japanese financial laws more similar to the US model than the European ones.

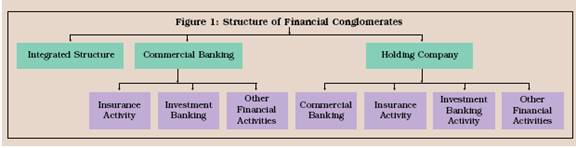

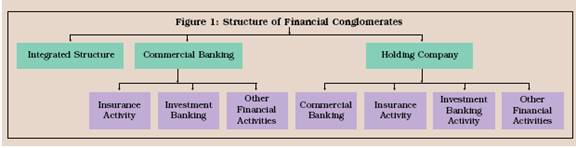

FCs vary greatly in terms of scope, structure of their business and the size across the countries. FCs could be structured on three different lines, viz., (i) the universal bank in which a bank undertakes non-traditional activities such asinsurance and securities trading in-house in separate departments; (ii) the holding company structure in which the bank is in one subsidiary of a holding company and the non-traditional activities are carried out by other subsidiaries of the holding company; and (iii) parent-subsidiary (operating subsidiary) in which the non-traditional activities are located in separate subsidiaries of the bank (Figure 1).

A pure integrated structure or universal bank is the one that creates and distributes financial products within a single corporate structure. In some cases, a universal bank combines commercial and investment banking within a single corporation but conducts other financial activities through separate subsidiaries. While a universal bank necessarily involves a banking activity, a FC need not. Thus, all the FCs need not be universal banks, while all universal banks could be treated as FCs. None of the major industrial countries allows a single corporate entity to provide services in all three financial sectors of banking, securities and insurance.

In the holding company structure as found in the US, a bank and other financial companies become affiliates under the same holding company. The GLB Act of 1999 removed the restrictions that limited the ability of US financial service providers, to affiliate with each other. However, such affiliations can occur only within a FHC’s structure. BHCs that qualify as a ‘FHC’ could engage in a broad array of financially related activities. To qualify as FHC, each depository institution subsidiary of the BHC must (i) be well capitalised and well managed; (ii) maintain at least a satisfactory Community Reinvestment Act rating ; and (iii) have a demonstrable record of providing low-cost basic banking services. A non-bank financial entity acquiring a bank is required to apply to the Federal Reserve Board to become a BHC. It could also file an application for a FHC if it meets the qualifying criteria.

An example of parent-subsidiary conglomerate is found in the UK and several emerging market economies, including India, whereby a commercial bank or other financial entity is allowed to set up subsidiaries to deal in other financial products.

References:

1. Tripartite Group of Bank, Securities and Insurance Regulators. 1995. The Supervision of Financial Conglomerates, July.

2. Raj, Janak. 2005. ‘‘Is there a Case for Super Regulator in India? Issues and Options’’. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. XLI, No. 35, 3846-3855, August 27-Septmber 2.

10.45 Each structure of financial conglomerates has its own advantages and disadvantages. The US was the first country to adopt the holding company structure and, therefore, has been the main centre for discussion on the ‘parent-subsidiary structure’ versus the ‘holding company structure’. The main argument in favour of the holding company structure advanced in the US is that it is safer and more sound and that it encourages competition. This, in turn, is based on the premise that the federal safety net comprising Federal deposit insurance, access to the Federal Reserve’s discount window and payments system may give banks certain financial advantages in the areas of funding and risk-taking over non-bank financial institutions. For these reasons, the operating subsidiary structure gives banks and their subsidiaries a competitive advantage over securities and insurance firms that remain independent of banks. The holding company structure that was supported by the Federal Reserve is believed to prevent the spread of the safety net and the accompanying moral hazard to the securities and insurance industries and assures a level playing field within the financial services industry. The Federal Reserve felt that it was critical that the subsidy implicit in the federal safety net be limited to those activities that a bank can conduct directly. It was of the view that operating subsidiaries would be a funnel for transferring the sovereign credit subsidy directly from the bank to finance any new principal activities into other entities thereby imparting a competitive advantage to such entities. This would inevitably lead to a weakening of the competitive strength of the US financial services industry as independent securities, insurance and other financial services providers would operate at a disadvantage to those owned by banks. The equity invested by banks in subsidiaries is funded by the sum of insured deposits and other bank borrowings that directly benefit from the subsidy of the safety net. Thus, inevitably, a bank subsidiary must have lower costs of capital than an independent entity and even a subsidiary of the bank’s parent. One would, therefore, expect that a rational banking organisation would, as much as possible, shift its non-bank activity from the bank holding company structure to the bank subsidiary structure. Such a shift from affiliates to bank subsidiaries would increase the subsidy and the competitive advantage of the entire banking organisation relative to the non-bank competitors (Greenspan, 1997).

10.46 A holding company structure, according to the Federal Reserve, achieves the full benefits of modernisation and has a proven track record of protecting safety and soundness, insulating the federal safety net, and providing competitive equality among companies that choose to affiliate with banks and those that choose to remain independent. It is, therefore, argued that by requiring non-bank activities to take place in separately capitalised subsidiaries of the holding company, the risk taking effects of those activities could be insulated from the bank and will not impose additional claims on the federal safety net, i.e., deposit insurance, the discount window and the payment system guarantees. The US regulators felt that the capital of the banking organisation and the federal safety net would be more seriously exposed to losses on securities and insurance activities under the parent-subsidiary relationship than under the holding company structure.

10.47 There are, however, also strong arguments in favour of the UK subsidiary-based model. It is argued that it represents the best practical universal banking approach and an organisational arrangement that can support important diversification gains, and at the same time is reasonably able to handle the regulatory imperfections, which make pure universal banking model untenable and the holding company structure inflexible. The operating subsidiary model, while requiring separation of activities between parent and subsidiaries, does not require the type of firewalls that are uniquely found in the holding company structure and has several advantages. First, by requiring that non-bank activities take place in separately capitalised subsidiaries of the bank, bank capital is in part protected from major unexpected losses in these areas. Second, by allowing a greater degree of integration between a bank and its non-bank subsidiaries, the potential to generate earnings through diversification effects is increased. Also, the potential for generating economies of scope, both on the cost and revenues sides, for the universal bank is enhanced. This, in turn, enhances the safety and soundness of the bank. Both diversification effects and economies of scope effects serve to reduce the probability that the safety net will be called into play. Forcing a financial services company - as a prerequisite for engaging in new activities - to transfer resources from its bank to its holding company would deplete the bank’s resources, leaving the bank’s earnings less diversified, and thus increasing risk to deposit insurance funds. Third, the UK model dovetails directly into the historical functional design of financial services regulation. Consequently, banking authorities could remain the primary regulators of the universal bank parent, while securities and insurance regulators for the securities market and insurance sector, respectively. Their policies could be coordinated through an appropriate mechanism such as lead regulator.

10.48 It is also argued that banks do not behave as if they enjoy subsidy. Even if there were a subsidy, the appropriate response should be to contain it carefully rather than to impose organisational constraints. Those who support operating subsidiary structure argue that potential losses in the operating subsidiary could be capped in such a way as to eliminate the exposure of the safety net. Investment by a bank in its operating subsidiary could be deducted from the regulatory capital of the bank, after which the bank’s regulatory capital position must still be deemed “well-capitalised.” Moreover, the bank would be prohibited from making good any of the debts of the failed subsidiary. However, the counter argument to this is that losses in, for example, securities dealing or insurance underwriting conducted in an operating subsidiary could occur so rapidly that they could overwhelm the parent bank before actions could be taken by the regulator. Put differently, losses in an operating subsidiary can easily far exceed a bank’s original equity investment long before the supervisor has any such knowledge. The resulting bank safety and soundness concerns are only deepened by the extent to which past retained earnings of the operating subsidiary would have strengthened the capital of the parent bank - an ostensible reason for setting up operating subsidiaries. Such a build-up in capital could be used to support other bank activities, and then eliminated by subsequent losses in the operating subsidiary, leaving the bank in an under-capitalised position. Thus, in the holding company structure, it is opined, all non-bank activities are subject to the same regulatory system and would protect banks and the federal deposit insurance system from the risk of failure of an operating subsidiary engaged in non-banking activity. 10.49 Some others, however, feel that there is no evidence of a safety net subsidy as has been made out. Any benefit banks receive from the safety net is more than offset by regulatory costs. A study about the linkage between organisational structure and the bank safety net reports that, measured by variability in the return on assets, securities subsidiaries set up by banks are less risky than those organised as holding company affiliates (Whalen, 2000). However, securities subsidiaries set up by banks tend to have lower capital than holding company subsidiaries so that the overall risk of the former could be higher. They also tend to have higher funding costs. This would be consistent with the argument that the operating subsidiaries are riskier than their holding company affiliated counterparts. However, the findings are inconclusive regarding the main question of the safety net subsidy.